First to the Victoria Falls

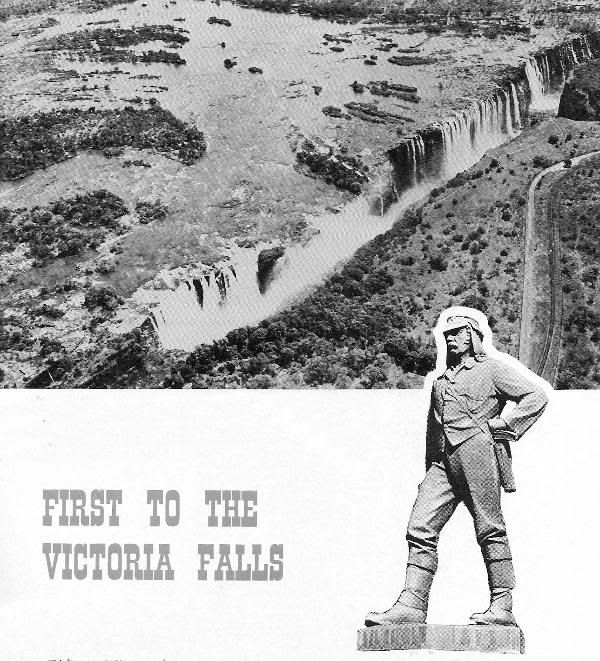

(Above) This aerial photograph of part of the Victoria Falls shows Livingstone's unusual first sight of the cataract. He came down river in a canoe to an island on the lip of the Falls (now named Livingstone Island), walked forward to the edge of the 100-metre deep chasm and gazed into the depths. A massive bronze statue (right) now overlooks the Devil's Cataract (not shown on main photograph).

IT was on November 16, 1855, that David Livingstone became the first European to sec the great waterfall which he named in honour of his Queen; but its presence had been known to his compatriots and,indeed, to Livingstone himself, for some years previously.

At the beginning of the present century, George Lacy, who had himself visited the Falls in 1868, enquired into the question of European knowledge of the Falls before Livingstone's visit.

Englishmen in the South had, as early as about 1840, heard reports of the existence, far away in the North of a phenomenon called Mosivatuna, 'the smoke that sounds'. No European, however, was within a hundred miles of them until 1851.

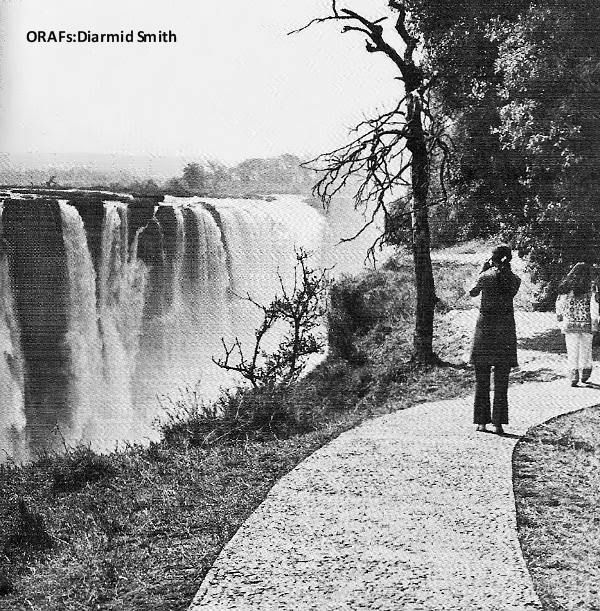

(Above) Although there has been development on the banks of the Zambezi above the Falls, there are large areas where the modern visitor can experience the wonder Livingstone felt as he canoed down from Kalai Island. But today's visitor may travel in the luxurious comfort of modern launches.

It was not until that year (1851) that the course of the upper Zambezi itself became known to outsiders. On August 3, 1851, David Livingstone and William Cotton Oswell reached the river at Mwandi. There they were told of the great waterfall that lay some distance downstream. However, they made no attempt to visit it on this occasion, but after a brief stay, retraced their steps southwards to Cape Town.

Oswell marked the position of the Victoria Falls — "waterfall, spray seen 10 miles off" — on a manuscript map which he produced on this occasion but which was not published for almost 50 years. It appears almost certain that Oswell did not himself approach within sight of the Falls, but that he obtained his information from Africans.

Thus, whether or not Livingstone and Oswell were the first Europeans to see the upper Zambezi, they were the first to make its presence known to the outside world.

After Livingstone's return to Cape Town in 1851-2, he sent his wife and children back to Europe, and retraced his steps to the Zambezi. Realising, that the route to the Zambezi from the south was potentially difficult and unreliable, he determined to investigate the practicability of opening up a route from either the east or west coast.

He struck north to the Zambezi and then west, arriving at Loanda in May, 1854. Realising the impracticability of this western route through Barotse country, he set out again, four months later, in a courageous attempt to cross the African continent to the Indian Ocean.

He struck north to the Zambezi and then west, arriving at Loanda in May, 1854. Realising the impracticability of this western route through Barotse country, he set out again, four months later, in a courageous attempt to cross the African continent to the Indian Ocean.

Almost exactly a year later he again arrived at the upper Zambezi. Here, as before, he heard tales of the great waterfall of Mosi-oa-Tunya, and on November 3, 1855, he set out to visit them.

Two days after leaving Old Shesheke, Livingstone reached Kalai Island. Livingstone reports that it was only twenty minutes after leaving Kalai that he first caught sight of the rising columns of spray, which he compared with the smoke from a large-scale bush fire. He was struck by the beauty of the river and its banks, which he described in the following terms:

The whole scene was extremely beautiful; the banks and islands dotted over the river are adorned with sylvan vegetation of great variety of colour and form. At the period of our visit several trees were spangled over with blossoms.

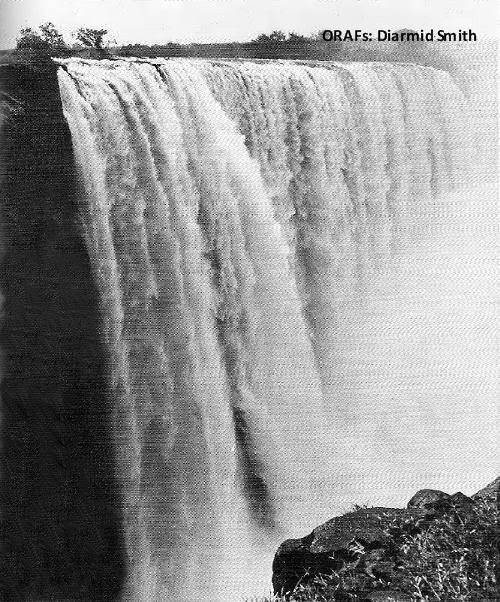

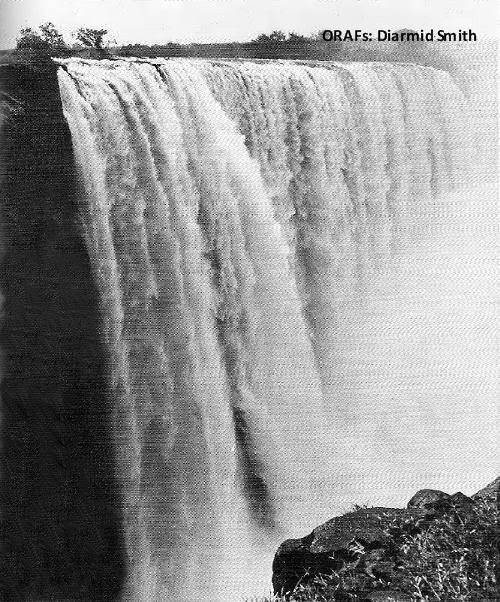

(Above) Part of the immense torrent of the Main Falls, which pour 93 metres into the gorge. As with all the pictures of the Falls in this article, this was taken when the water level as reasonably low, for the ascending spray obscures the view.

No-one could perceive where the vast body of water went, it seemed to lose itself in the earth, the opposite lip of the fissure into which it disappeared being only eight feet distant. Creeping with awe to the verge, I peered down into a large rent which had been made from bank to bank of the broad Zambesi, and saw that a stream of a thousand yards broad leaped down a hundred feet, and then became suddenly compressed into a space of fifteen or twenty yards*... the most wonderful sight I had witnessed in Africa. In looking down into the fissure on the right of the island, one sees nothing but a dense white cloud which, at the time we visited the spot, had two bright rainbows on it.... The snow-white sheet seemed like myriads of small comets rushing in one direction, each of which left behind its nucleus rays of foam.

* These figures are, of course, a gross underestimate.

Leaving the Falls, Livingstone reached the Indian Ocean, at Quelimane in May, 1856. Thence he returned to England, but returned two years later, having been appointed H. M. Consul for the East Coast of Africa to the south of Zanzibar and for the unexplored Interior. It was on this occasion that Livingstone paid his second and last visit to the Victoria Falls.

Two days after leaving Old Shesheke, Livingstone reached Kalai Island. Livingstone reports that it was only twenty minutes after leaving Kalai that he first caught sight of the rising columns of spray, which he compared with the smoke from a large-scale bush fire. He was struck by the beauty of the river and its banks, which he described in the following terms:

The whole scene was extremely beautiful; the banks and islands dotted over the river are adorned with sylvan vegetation of great variety of colour and form. At the period of our visit several trees were spangled over with blossoms.

There, towering over all, stands the great burly baobab, each of whose arms would form the trunk of a large tree, besides groups of graceful palms, which with their feathery-shaped leaves depicted on the sky, lend their beauty to the scene. The silvery mohonono, which in the tropics is in form like the cedar of Lebanon, stands in pleasing contrast with the dark colour of the motsouri, whose cypress-like form is dotted over at present with its scarlet fruit. Some trees resemble the great spreading oak, others assume the character of our own elms and chestnuts; but no one can imagine the beauty of the view from anything witnessed in England. It had never been seen before by European eyes; but scenes so lovely must have been gazed

upon by angels in their flight.

(Above) Part of the immense torrent of the Main Falls, which pour 93 metres into the gorge. As with all the pictures of the Falls in this article, this was taken when the water level as reasonably low, for the ascending spray obscures the view.

About one kilometre upstream of the Falls he transferred to a smaller, lighter canoe and proceeded in this to the island between the Main and Rainbow Falls which is today called Livingstone Island. Landing on the island, he obtained his first view of the Falls from what is surely the most impressive of all viewpoints. The moment is best described in Livingstone's own words:

No-one could perceive where the vast body of water went, it seemed to lose itself in the earth, the opposite lip of the fissure into which it disappeared being only eight feet distant. Creeping with awe to the verge, I peered down into a large rent which had been made from bank to bank of the broad Zambesi, and saw that a stream of a thousand yards broad leaped down a hundred feet, and then became suddenly compressed into a space of fifteen or twenty yards*... the most wonderful sight I had witnessed in Africa. In looking down into the fissure on the right of the island, one sees nothing but a dense white cloud which, at the time we visited the spot, had two bright rainbows on it.... The snow-white sheet seemed like myriads of small comets rushing in one direction, each of which left behind its nucleus rays of foam.

* These figures are, of course, a gross underestimate.

Leaving the Falls, Livingstone reached the Indian Ocean, at Quelimane in May, 1856. Thence he returned to England, but returned two years later, having been appointed H. M. Consul for the East Coast of Africa to the south of Zanzibar and for the unexplored Interior. It was on this occasion that Livingstone paid his second and last visit to the Victoria Falls.

Following Livingstone's first visit, the next European to visit the Falls was William Baldwin, who arrived on August 2, 1860. Baldwin was an English hunter who spent much of the decade from 1851 wandering widely between Natal and the Zambezi. He found his way to the Falls, via the Chobe River, by pocket compass.

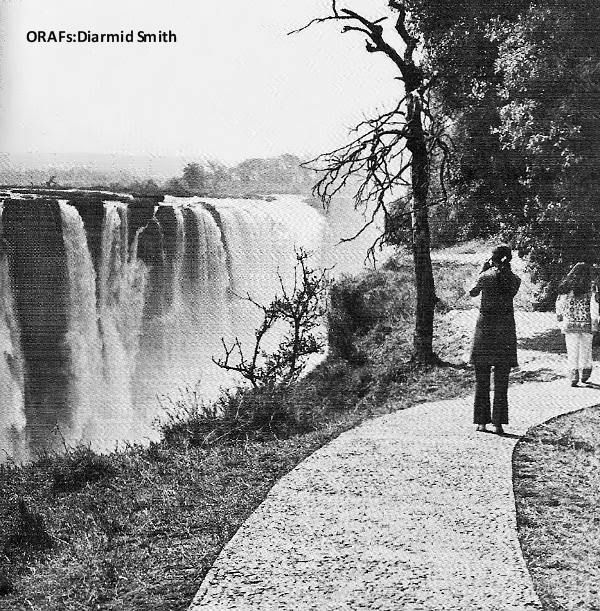

(Above) The modern visitor to the Victoria Falls suffers none of the discomfort of those early tourists, who had to force their way through dense bush to gain a view of the waterfall. Now, through the Rain Forest a complex of paths guide the visitor to vantage points overlooking each part of the 1 708-metre wide cataract.

During the following decade several further Europeans, mainly hunters, reached the Victoria Falls. By 1870 the names of twenty-five such visitors are recorded, but there were undoubtedly several others whose names have not been preserved. During the two years 1874-75, however, these numbers were doubled, indicating the rate at which the area was being drawn into the sphere of European activity centred on South Africa.

What 19th century visitors wrote about the Falls

DAVID AND CHARLES LIVINGSTONE, 1865

The Victoria Falls have been formed by a crack across the river, in the hard, black, basaltic rock which there formed the bed of the Zambesi. Into this chasm, of twice the depth of Niagara-fall, llie river, a full mile wide, rolls with a deafening roar; and this is Mosi-oa-Tunya or the Victoria Falls. The whole body of water rolls clear over, quite unbroken; but after a descent of ten or more feet, becomes like a huge sheet of driven snow.

JAMES CHAPMAN, 1868

Nothing can be more dclicately beautiful and pleasing to the eye than the milky streams, broken at the top by dividing rocks and widening to the base, pouring down in one unbroken flow of snowy whiteness from a height of upwards of 300 feet.

EDUARD MOHR, 1876

It seemed to me as if my own identity was swallowed up in the surrounding glory, the voice of which rolled on forever, like the waves of eternity . . . No human being can describe the infinite ; and what I saw was a part of infinity made visible and framed in beauty.

FREDERICK COURTENEY SELOUS, 1881

Such arc the Victoria Falls — one of, if not the, most transcendentally beautiful natural phenomena on this side of Paradise.

EMIL HOLUB, 1881

Nor does the magnificence of the view end with the prospect of the giant waterfall itself. Let us raise our eyes towards the blue horizon; another glorious spectacle awaits us. Stretching far away in the distance are the numerous islands with which the river-bed is studded; the gorgeous verdure of their fan-palms standing out in striking contrast to the subdued azure of the hills behind.

All around them, furnishing a deep blue bordering, lies the expanse of the mighty stream that moves so placidly that at first it might seem to be without movement at all; but gradually as it proceeds it acquires a sensible increase in velocity . . . to take its mighty plunge into the deep abyss.

A. A. de SERPA PINTO, 1881

That enormous gulf, black as is the basalt which forms it, dark and dense as the cloud which enwraps it, would have been chosen} if known in biblical times, as an image of the infernal regions, a hell of water and darkness, more terrible perhaps than the hell of fire and light.

L DECLE, 1898 .

I expected to find something superb, grand, marvellous. I had never been so disappointed ... It

is hell itelf, a corner of which seems to open at your feet; a dark and terrible hell, from the middle of which you expect every moment to sec some repulsive monster rising in anger.

End of Article

Baldwin made the first reasonably accurate estimate of the size of the Falls; he considered them to be two thousand yards wide and three hundred feet high. For eye-estimates these are remarkably close to the true figures and a great improvement on the gross underestimate made by Livingstone in 1855.

On this occasion, David andCharles Livingstone stayed on at the Falls after Baldwin's departure and were able to make a much more detailed examination of the area than had been possible five years earlier. They crossed to the south bank and explored the Rain Forest there; this was probably the only occasion on which David Livingstone set foot in what is now Rhodesia. Detailed measurements were made, and the total width of the Falls was found.

Baines records that he visited Livingstone Island and found that the garden which David Livingstone had planted there had been trampled by hippopotami and was completely overgrown. It was on this occasion that Baines executed the fine paintings of the Falls which he published in 1863.On this occasion, David andCharles Livingstone stayed on at the Falls after Baldwin's departure and were able to make a much more detailed examination of the area than had been possible five years earlier. They crossed to the south bank and explored the Rain Forest there; this was probably the only occasion on which David Livingstone set foot in what is now Rhodesia. Detailed measurements were made, and the total width of the Falls was found.

Livingstone's subsequent explorations took him far away from the Victoria Falls region, and we must now turn to the steadily increasing numbers of Europeans who found their way to the Falls. A few Boer hunters are known to have visited them during 1801 but it appears that only one, Martinus Swartz, survived the return journey.

(Above) This is part of a remarkable high-altitude photograph of the Victoria Falls in THE HANDBOOK. It shows clearly the complex of deep gorges below the Falls through which the Zambezi, restricted from a bed 1 708 metres wide to one 50 metres wide in parts, boils and surges its Way Each gorge parallel with the present Victoria Falls is a falls of the past, a theory well explained in the geological chapter of the book.

The visitors of 1862 are again well documented, being James Chapman and Thomas Raines, both of whom published accounts of their travels, accompanied by Edward Barry. Chapman, a hunter and trader, had born near the Chobe in August, 1853, and, had he then been told of the proximity uf the Falls, as Oswell was in 1851, would have been in a position to anticipate Livingstone's visit by over two years. In 1862 he and Baines reached the Victoria Falls on their great journey which had begun at Walvis Bay on the Atlantic coast.

(Above) The modern visitor to the Victoria Falls suffers none of the discomfort of those early tourists, who had to force their way through dense bush to gain a view of the waterfall. Now, through the Rain Forest a complex of paths guide the visitor to vantage points overlooking each part of the 1 708-metre wide cataract.

During the following decade several further Europeans, mainly hunters, reached the Victoria Falls. By 1870 the names of twenty-five such visitors are recorded, but there were undoubtedly several others whose names have not been preserved. During the two years 1874-75, however, these numbers were doubled, indicating the rate at which the area was being drawn into the sphere of European activity centred on South Africa.

What 19th century visitors wrote about the Falls

DAVID AND CHARLES LIVINGSTONE, 1865

The Victoria Falls have been formed by a crack across the river, in the hard, black, basaltic rock which there formed the bed of the Zambesi. Into this chasm, of twice the depth of Niagara-fall, llie river, a full mile wide, rolls with a deafening roar; and this is Mosi-oa-Tunya or the Victoria Falls. The whole body of water rolls clear over, quite unbroken; but after a descent of ten or more feet, becomes like a huge sheet of driven snow.

JAMES CHAPMAN, 1868

Nothing can be more dclicately beautiful and pleasing to the eye than the milky streams, broken at the top by dividing rocks and widening to the base, pouring down in one unbroken flow of snowy whiteness from a height of upwards of 300 feet.

EDUARD MOHR, 1876

It seemed to me as if my own identity was swallowed up in the surrounding glory, the voice of which rolled on forever, like the waves of eternity . . . No human being can describe the infinite ; and what I saw was a part of infinity made visible and framed in beauty.

FREDERICK COURTENEY SELOUS, 1881

Such arc the Victoria Falls — one of, if not the, most transcendentally beautiful natural phenomena on this side of Paradise.

EMIL HOLUB, 1881

Nor does the magnificence of the view end with the prospect of the giant waterfall itself. Let us raise our eyes towards the blue horizon; another glorious spectacle awaits us. Stretching far away in the distance are the numerous islands with which the river-bed is studded; the gorgeous verdure of their fan-palms standing out in striking contrast to the subdued azure of the hills behind.

All around them, furnishing a deep blue bordering, lies the expanse of the mighty stream that moves so placidly that at first it might seem to be without movement at all; but gradually as it proceeds it acquires a sensible increase in velocity . . . to take its mighty plunge into the deep abyss.

A. A. de SERPA PINTO, 1881

That enormous gulf, black as is the basalt which forms it, dark and dense as the cloud which enwraps it, would have been chosen} if known in biblical times, as an image of the infernal regions, a hell of water and darkness, more terrible perhaps than the hell of fire and light.

L DECLE, 1898 .

I expected to find something superb, grand, marvellous. I had never been so disappointed ... It

is hell itelf, a corner of which seems to open at your feet; a dark and terrible hell, from the middle of which you expect every moment to sec some repulsive monster rising in anger.

End of Article

Extracted and recompiled, by Eddy Norris, from a publication which was made available to ORAFs by Diarmid Smith . Thank you Diarmid

Original publication was Rhodesia Calls dated March -April 1976

The recompilation was done for no or intended financial gain but rather to record the memories of Rhodesia.

Original publication was Rhodesia Calls dated March -April 1976

The recompilation was done for no or intended financial gain but rather to record the memories of Rhodesia.

Thanks to

Paul Norris for the ISP sponsorship.

Paul Mroz for the image hosting sponsorship.

Robb Ellis for his assistance.

Should you wish to contact Eddy Norris please mail me on orafs11@gmail.com

3 Comments:

Brilliant work Eddy, you are a David Livingstone of this age, recording our history for posterity and making it so easy for armchair travellers to access, read and wonder at.

Thanks Eddy. You are Rhodesian's Unsung Hero of History.

I am thrilled to share that I have successfully cleared the CompTIA A+ 220-1101 (Core 1) examination with top scores. The exceptional study guides and preparatory tools from ValidTests.com were pivotal to my success, equipping me with the necessary understanding and self-assurance to achieve outstanding results in this essential IT fundamentals certification.

Smart savings for smart goals: https://www.validtests.com/comptia/exam/220-1101

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home