Rhodesia- The Years Between

Cover

THE YEARS BETWEEN

1923 - 1973

HALF A CENTURY OF RESPONSIBLE GOVERNMENT IN RHODESIA

by

W. D. GALE, M.B.E.

The Clamour for Self-Government.

Tackling (The Problem.

Disposing of the Land.

Steady Expansion.

The Federal Experiment.

Tho New Leaders.

Patience Runs Out.

The Settlement Terms.

Proposals for Settlement.

The Test of Acceptability.

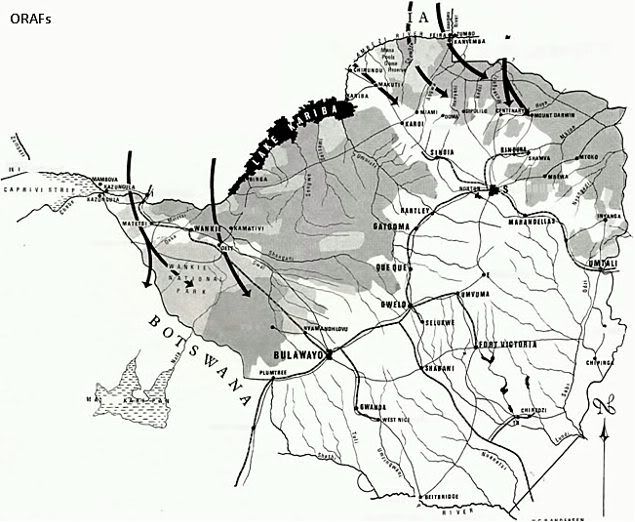

The Terrorist Threat.

A Flourishing Economy.

Chronological Table.

Contributed

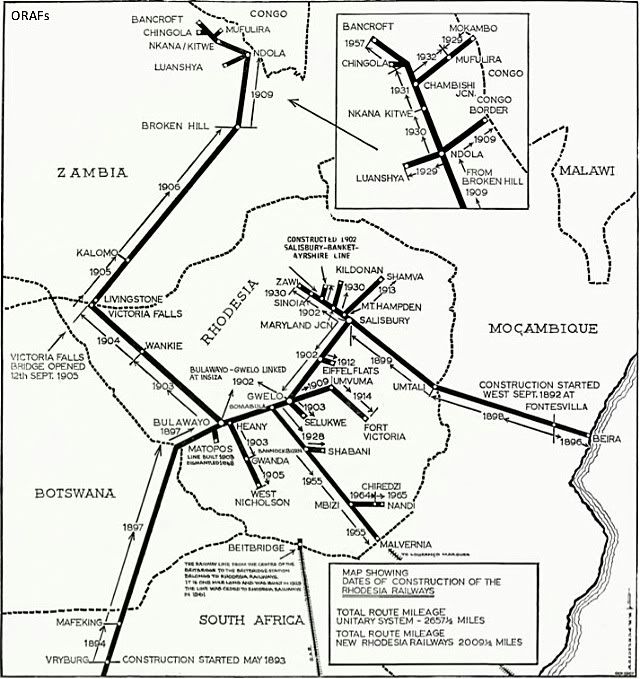

You Cannot Plan Without a Map

Maps

Construction of Rhodesia Railways.

Terrorist Invasion Routes.

Index to Participants.

Except where stated otherwise, the photographs in this volume are acknowledged to the National Archives and the Photographic Unit, Ministry of Information.

Designed, Compiled and Published by: H. C. P. Andersen, P.O. Box 1566. Salisbury, Rhodesia

Printed in Rhodesia by: Mardon Printers (Pvt.) Ltd., at Salisbury.

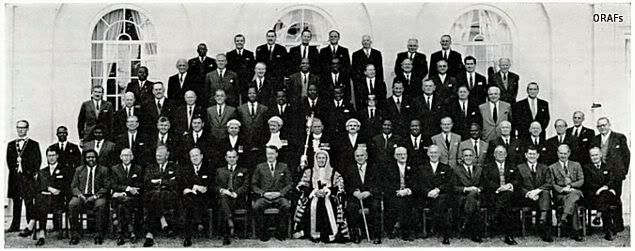

COUNCIL THAT BECAME PARLIAMENT

The Legislative Council, precursor of the Parliament of today, consisted of nominated members of the Chartered Company's Administration and of members elected by the people. This photograph was taken in 1914 and includes many who were later to become members of the First Legislative Assembly under responsible government

Front row, from left to right: Mr. (later Sir) Ernest Montagu; Major Gordon Forbes; Mr.

(later Sir) Francis Newton; Colonel Burnes Begg; Sir William Milton; Sir Charles Coghlan;

Colonel (later Sir) Raleigh Grey; Mr. (later Sir) Clarkson Tredgold.

Middle row, left to right: Mr. J. H. Kennedy; Mr. E. A. Begbie; Mr. B. I. CoUings; Mr. Arnold Edmonds; Mr. Lionel Cripps; Mr. George Mitchell; Dr. Eric Nobbs; Mr. George Duthie;

(later Sir) Francis Newton; Colonel Burnes Begg; Sir William Milton; Sir Charles Coghlan;

Colonel (later Sir) Raleigh Grey; Mr. (later Sir) Clarkson Tredgold.

Mr. M. E. Cleveland; Colonel (later Sir) Melville Heyman.

Back row, left to right: Mr. Colin Duff; Mr. James Robertson; Captain W. Bucknall;

Colonel W. Napier; Mr. Elles Edwards.

THE CLAMOUR FOR SELF - GOVERNMENT

FIFTY years ago the loyal British Colony of Southern Rhodesia was a quiet backwater well removed from the main stream of world affairs. Lacking a sea coast of her own, locked in by vast, poorly developed territories to the east, west and north, and by the infinitely greater and more vigorous Union of South Africa in the south, she lay well outside the beaten tracks of international communications, for in those days the steamship was the main medium of world transport. The aeroplane was in its flimsy infancy, and so was the radio, while the telephone was still a primitive instrument. The motorcar was a novelty, roads were sandy, potholed tracks and there was not a single road bridge across river or donga from one end of the country to the other. The horse and the ox were supreme and time was of no account. Life was placid and easy-going; the ulcer and the coronary thrombosis ranked well below malaria and black-water fever as a menace to human life. Nobody was very rich, but nobody was very poor, either, and since they were all members of the same isolated little community everybody knew everyone else, and everyone was an individual in his own right, especially if his skin was white. There were so few white skins and so many black skins, but they all lived happily together within the same boundaries. In many ways it was an idyllic existence, with its drawbacks, certainly, even with certain hardships, but since standards were the same for everybody nobody minded.

But that is not to say that nothing ever happened. In fact, a great deal had been happening, in the political sense, which was to change the face of the country and set Southern Rhodesia on a new course that was to bring her eventually to the forefront of world attention. For her first thirty-three years of European colonisation, she had been administered by the British South Africa Company, founded by Cecil Rhodes on the basis of a charter granted by Queen Victoria in 1889. which enjoyed great commercial as well as administrative privileges, and the residents had had little say in the direction of affairs. Major decisions were made by the Company's Board of Directors sitting in London and carried out by the Company's officials in Salisbury. The only opportunity the local population had of discussing, and if necessary objecting to, decisions that affected the very warp and weft of their lives, was in the Legislative Council in which both people's representatives and Company officials sat together under the chairmanship of the Administrator, with the latter having majority control so that the Company's viewpoint predominated. During Cecil Rhodes' lifetime the Company's policies had had a breadth of vision, and a feeling for the interests of the people on the spot, that enabled Company and settlers (as they were then called) to get along reasonably well together. But when Rhodes died in 1902 at the early age of 48, the people lost their champion and the Board lost its vision. Thereafter it seemed to the settlers that the Board's decisions were actuated by dreary commercial considerations, that the interests of the Company came before those of the people, and that it was using its administrative privileges for its own commercial advantage.

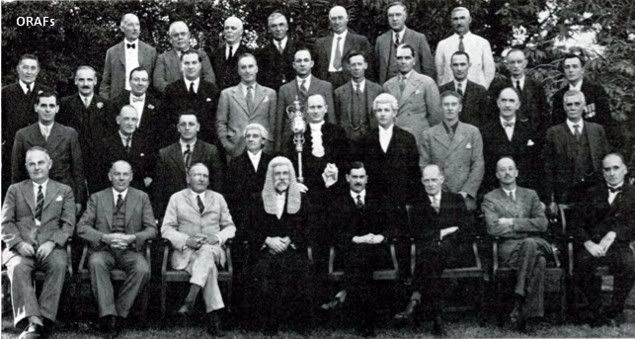

MEMBERS OF THE LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL, 1st SESSION 7th COUNCIL, 1920

Front row, left to right: R. Mcllwaine, Solicitor-General; P. D. L. Fynn, Treasurer;

Mrs. E. Tawse-Jollie; C. D. Douglas-Jones, C.M.G.Resident Commissioner; Sir D. Chaplin, K.C.M.G., Administrator; Sir Charles Coghlan; E. W. S. Montagu, Secretary for Mines and Works; J. McChlery; G. H. Eyre, Postmaster-General.

Second row, left to right: J. B. MacDonald; W. J. Boggie; W. D. Douglas-Jones; R. D. Gilchrist; E. A. Nobbs, Director of Agriculture;

J. D. MacKenzie, Attorney-General; J. Stewart; F. L. Hadfield.

Third row, left to right: L. Cripps; H. U. Moffat; R. A. Fletcher; W. M. Leggate.

Back row, left to right: J. G. Jearey, Clerk of Councils; A. R. Hone, Secretary; J. B. Grenfell-Hicks, Assistant Clerk.

The Rhodesians of those days were sturdy individualists. They had to be to survive. They were men and women of independent thought, accustomed to thinking for themselves, not at all inclined to meekly accept the dictates of titled gentlemen sitting in the cosy confines of their panelled boardroom in London Wall, issuing edicts that affected the lives of men battling against drought and flood and disease and poor markets and the thousand difficulties of life in a sub-tropical, poorly developed country. They objected to the fruits of their strenuous labours being diverted into the coffers of a commercial company, to the benefit (as they imagined) of unknown shareholders who naturally wanted to see a return on their money. As it happened the shareholders gained little. The cost of running the country barely kept pace with the revenue, and in most years the Company ended up with a deficit. But this did not deter the settlers from concluding that they could run the country better themselves. And so began the clamour for self-government.

It was led by a Bulawayo lawyer named Sir Charles Coghlan, the senior partner in the country's leading legal firm. Born in South Africa of Irish extraction, Coghlan had settled in Bulawayo in 1900 immediately after the lifting of the siege of Kimberley, in which he had played a worthy part as commander of redoubt. He soon began to take an interest in the affairs of his adopted country, and in 1907 emerged into the political limelight when he was chosen, with two others, to put the people's case to a party of Chartered Company directors from London, led by Dr. Starr Jameson, who were to investigate the settler's grievances.

Coghlan was particularly concerned at the Company's practice of diverting taxation revenue to its commercial accounts instead of applying it to the cost of the country's administration. He also objected to the Company's assumed right to dispose of land as it wished, usually to the friends of directors, and he accused the Company of abusing its legislative power in its own interests. So skilfully did he present his case that he became recognised as the champion of the people's rights, and after some hard bargaining he managed to secure some small but welcome concessions in regard to the mining laws, land titles and the allocation of revenues. His biggest gain, however, was to induce the Directors to reduce the number of officials on the Legislative Council from seven (which gave the people's representatives parity) to five, which gave them a majority on all except fiscal matters. He had hitherto refused to stand for election to the Legislative Council because of the official majority, but now that this barrier had been removed he offered himself for election in the general election of 1908.

A story is told of Coghlan's candidature which illustrates the tactics adopted by Company representatives in these matters, and also Coghlan's character. He was visiting relatives at Pietersburg in the Transvaal towards the end of 1907 when he received a telegram from his partner at Bulawayo, Allan Welsh (later Sir Allan Welsh, who became Speaker of the Southern Rhodesia Parliament) urging him to stand in the elections due early the following year. He was considering the matter when he received another telegram, this time from Mr. (later Sir) J. G. McDonald, a strong Company man, threatening that if he accepted nomination he (McDonald) would withdraw the business of all his companies from the legal firm of Coghlan and Welsh. That did it. Coghlan immediately wired Welsh to say that he accepted. He stood for the Western Division of Matabeleland, and after a hectic campaign was returned as senior member in April, 1908.

He was appointed leader of the Elected Members, and as such was chosen with two other delegates to represent Southern Rhodesia at the National Convention of the four South African States of the Cape Colony, Natal, Orange Free State and Transvaal, held at Durban in October, 1908. Its purpose was to consider whether the South African States should unite or federate, and Southern Rhodesia was invited as an interested party. At that time Coghlan believed that if South Africa united Rhodesia should enter the new State without delay, but at the Convention he was disillusioned by General J. B. M. Hertzog's implacable hostility to everything British and his uncompromising championship of Afrikanerdom. At the same time he was convinced that Rhodesia should ultimately become a part of the South African nation, and he was instrumental in seeing that the draft Bill (which later became the South Africa Act) provided for Rhodesia to decide at some future date whether and on what terms she should enter the Union of South Africa.

Caption

WINSTON CHURCHILL, who succeeded Lord Milner at the Colonial Office, was strongly in favour of Rhodesia joining the Union of South Africa, but eventually thought that Britain's terms for granting self-government a "very fair deal".

He explained his reasons after his return to Bulawayo.

The plight of Rhodesia under the control of a commercial corporation was most unsatisfactory, he said, and it was essential that the people should take over the reins of government. But not yet. The European population was too small to justify any claim to self-government at that stage. An alternative would be to join the Union of South Africa—but again, not yet. When the time came they must be able to do so freely and willingly, not as beggars but on equal terms, able to insist on fair and just treatment. In the meantime they must get on with developing the country.

The Union of South Africa came into being on May 31, 1910, and Coghlan was knighted for his services at the Convention, where his knowledge of constitutional law had been of the utmost value. He was the first Rhodesian, other than a Chartered Company civil servant, to receive a knighthood.

The running battle between the settlers and the Company continued. Small concessions were gained in the form of lower railway rates and easier tariff's, and the vexed question of the ownership of the land was referred to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. All this skirmishing was carried on with an eye to the ending of the Company's charter, for the original charter of 1889 was granted for a period of 25 years and was thus due to expire in 1914. But Coghlan and his colleagues viewed its termination with a certain amount of misgiving. They were by no means ready to replace the Company. The rising tide of Afrikaner nationalism ruled out any desire to enter the Union, and the prospect of direct Colonial Office rule had little appeal. The outbreak of the First World War on August 4, 1914, solved their dilemma. It was agreed that the country's best interests would be served by maintaining the status quo, and the Companys' charter was extended for a further ten years.

Politics went into the background as Rhodesia threw herself into the common war effort. In the Legislative Council Coghlan moved as an unopposed motion that the Company should recruit and train a thousand men for the armed forces, that the proceeds of new customs and excise duties be devoted to war purposes and that no part of the expense should be allowed to fall on the Chartered Company's private funds. But the Company was tardy in giving effect to the proposal to raise an armed force, and many men paid their own expenses to England to join British units. But other eager volunteers could not afford the cost, and a private recruiting campaign was launched by Coghlan's legal partner, Ernest Guest, who organised a private fund to pay their passages. These men were sent in a body to England and formed the Rhodesian platoon of the King's Royal Rifle Corps, in which they served with distinction. Shortly afterwards a battalion of the Rhodesia Regiment was raised by the Administration which served in the German South West Africa campaign, and when this ended Rhodesian troops, both European and African, endured the gruelling campaign in German East Africa, where the malarial mosquito was more deadly than the bullet.

Altogether, 6831 white Rhodesians went on active service in that war, representing 64 per cent of all European males between the ages of 15 and 44 and 25 per cent of the total European population. Seven hundred and thirty-two of them were killed or died of wounds or disease. The number of Africans who served with the Rhodesia Native Regiment in East Africa was 2 360, with another 360 in other services. It was a remarkable contribution for so small a country—the

highest in the Commonwealth in proportion to the total white population—but a heavy price was paid in development. Many farms and mines and businesses were abandoned, and although the women left behind did their utmost to keep things going the country as a whole suffered a severe economic setback.

The war effort was temporarily pushed into the background when, towards the end of 1916, the Chartered Company sent out two directors. Sir Starr Jameson and Dougal Malcolm, with the proposal that Southern Rhodesia and Northern Rhodesia (for the administration of which it was also responsible) should be amalgamated to reduce administrative costs in the interests of the shareholders. Both the administrative and commercial headquarters would be in Salisbury, staffs would be reduced, customs barriers between the two countries would disappear, railway rates would be lowered so that Southern Rhodesia's farmers would be able to compete more favourably in the Congo market, and native labour would become more plentiful. The idea certainly had advantages.

But it also had its snags, and Sir Charles Coghlan and his elected colleagues were quick to point them out. Southern Rhodesia would probably have to carry Northern Rhodesia's deficits as' well as her own, the small European population would become responsible for a much greater African population and would be overwhelmed by sheer weight of numbers. Already struggling against odds in upholding civilized standards of political and social life, the white voters would be swamped by a spate of black voters from beyond the Zambezi, where numbers of them could easily satisfy the simple education test for the franchise. Domination by the "Black North" would be a very real prospect.

But the greatest objection of all, in Coghlan's eyes, was that amalgamation would probably postpone the granting of self-government, which would be more easily attained if Southern Rhodesia were kept to its present bounds. So when the Company moved a formal motion in the Legislative Council session of April, 1917, favouring amalgamation, Coghlan and most of his colleagues voted against it. Three of the elected members voted with the Company's official members to carry it by a small majority, but in view of the opposition of most of the people's representatives the scheme was not proceeded with. In the circumstances of the time, Coghlan's attitude had a lot to justify it since his principal objective was self-government, but looking back in the light of subsequent developments the verdict must be that a great opportunity was missed.

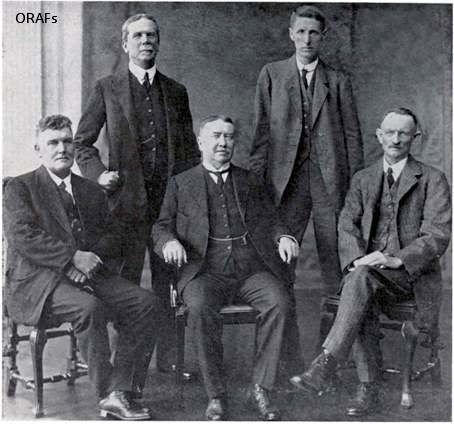

Caption

RESPONSIBLE GOVERNMENT DELEGATION TO LONDON, 1922

Left to right, seated: J. McChlery; Sir Charles Coghlan, R. A. Fletcher.

Left to right, standing: Sir Francis Newton; W. M. Leggate.

Left to right, standing: Sir Francis Newton; W. M. Leggate.

The Judicial Committee of the Privy Council gave its decision on the ownership of the land of Southern Rhodesia towards the end of 1917. It was that the Chartered Company had no title to the un-alienated lands, but, so long as it administered Southern Rhodesia under the Crown it was entitled to dispose of them and apply the resulting revenue to reimburse itself for its administrative costs. This considerably cleared the air for determining the country's future.

The clamour for self-government grew—and so did the urgings of those who favoured entry into the Union. The champions of responsible government pointed to a danger arising out of the land decision—that if Rhodesia became a part of South Africa Southern Rhodesia's land would come under South African control and it could be used to settle thousands of landless Boers. And that, they argued, would jeopardise Southern Rhodesia's predominantly British character.

To Coghlan's dismay, some powerful voices were stepping up the pressure to join the Union. Lord Milner, who had been British High Commissioner in South Africa and was now Secretary for the Colonies, stated officially that in view of the small numbers of the European population as compared with the African, he did not consider that Southern Rhodesia was equal to the financial burden of self-government. Since direct rule by Whitehall was out of the question, the only alternative was to join the Union, a course which was favoured by the British Government and which was also powerfully advocated by General Smuts, who stood high in Imperial favour both as a soldier and a statesman The odds against self-government seemed overwhelming, and the Responsible Government League girded its loins in 1919 to do battle with the Rhodesia Union Association in the first post-war elections to be held the following year, which would clearly indicate the people's will.

The issue was a straight fight between the two factions for the 13 elected seats in the Legislative Council, and each side contested every seat. It was hard fought and the controversy raged up and down the land. The result was an overwhelming victory for the Responsible Government candidates, led by Coghlan, who won 12 seats, with only one going to the Unionists. At the first session of the new Council Coghlan moved a motion praying "the King's Most Excellent Majesty to establish forthwith in Southern Rhodesia the form of government known as Responsible Government, urgently required for the proper development of its resources and the freedom and prosperity of its people". It was carried by 12 votes to 5.

But the end of the road was nowhere in sight. In the House of Commons the critics, always vociferous where Southern Rhodesia was concerned, protested at the fate of 800 000 Africans being left in the hands of a small European population, and the Colonial Office dragged its feet. A Royal Commission under Lord Cave had been appointed to examine the financial implications of self-government, particularly the extent of the Chartered Company's deficits and to determine what compensation would be due to it on termination of the Charter. It showed no sense of urgency and its deliberation dragged on for months. It finally reported in January, 1921, and put the territory's debt to the Chartered Company at just over £3 000 000, mainly for public works.

At about the same time Winston Churchill succeeded Lord Milner at the Colonial Office and gave a new impetus to finalising Southern Rhodesia's future. He appointed the Buxton Commission to advise him as to when, and with what limitations, if any, responsible government should be granted, and the form the new Constitution should take. Lord Buxton and his colleagues got down to work with commendable despatch and reported in May that the existing position should be ended as soon as possible and that the elections of 1920 had clearly shown the people's wishes. They recommended that a deputation of elected members should visit London as soon as possible to help the Colonial Secretary draft the Constitution.

It was arranged that the deputation should visit London in the latter part of 1921. As the time for its departure approached, Coghlan found himself under considerable pressure to abandon Responsible Government in favour of entry into the Union. He was offered a seat in the South African Cabinet and blandishments were showered on him. But he resisted all temptation and refused to exchange "the legal for the political way of making bread and butter". But he did agree, at Churchill's insistence, that the deputation should visit General Smuts at Pretoria on its way to England, although the purpose was not at all clear since "nothing can influence us in carrying out the object for which we were elected and for which the deputation is going to England, namely, to settle a Responsible Government Constitution for Southern Rhodesia. Union does not come into the matter at all". The meeting was inconclusive. Smuts was "as charming as ever and very flattering," wrote Coghlan after a private interview between them, held at Smut's request. If the South African Prime Minister was disappointed at not being able to shake Coghlan's resolution, the Rhodesian leader was equally disappointed at not being able to induce Smuts to drop the Union issue.

The deputation found that Churchill himself was strongly in favour of Rhodesia joining the Union. Smuts wanted the support of Rhodesians in his Parliament to bolster his position against the growing strength of Afrikaner National-

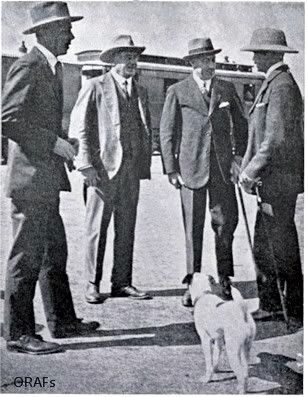

Caption

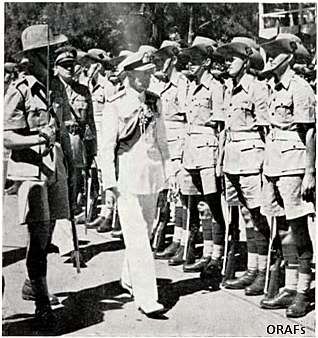

1923. The visit oj the first Governor of Southern Rhodesia, Sir John Chancellor, to Gatooma.

Left to right. Captain Lowther, A.D.C., Mr. T J. Golding, Mayor; Lt.-Col. Sir John Chancellor,

K C.M.G., G.C.V.O , R.E, and the Magistrate of Gatooma.

K C.M.G., G.C.V.O , R.E, and the Magistrate of Gatooma.

It was arranged that the deputation should visit London in the latter part of 1921. As the time for its departure approached, Coghlan found himself under considerable pressure to abandon Responsible Government in favour of entry into the Union. He was offered a seat in the South African Cabinet and blandishments were showered on him. But he resisted all temptation and refused to exchange "the legal for the political way of making bread and butter". But he did agree, at Churchill's insistence, that the deputation should visit General Smuts at Pretoria on its way to England, although the purpose was not at all clear since "nothing can influence us in carrying out the object for which we were elected and for which the deputation is going to England, namely, to settle a Responsible Government Constitution for Southern Rhodesia. Union does not come into the matter at all". The meeting was inconclusive. Smuts was "as charming as ever and very flattering," wrote Coghlan after a private interview between them, held at Smut's request. If the South African Prime Minister was disappointed at not being able to shake Coghlan's resolution, the Rhodesian leader was equally disappointed at not being able to induce Smuts to drop the Union issue.

The deputation found that Churchill himself was strongly in favour of Rhodesia joining the Union. Smuts wanted the support of Rhodesians in his Parliament to bolster his position against the growing strength of Afrikaner Nationalism, and to Churchill this seemed desirable. Coghlan objected on the grounds that Rhodesian representation would have little eflfect and that the country would make faster progress if it governed itself than if it became a backwater appendage of the more powerful South Africa. He also emphasised the loyalty of Rhodesians to their British heritage and character and the magnitude of their contribution to the common effort in the late war, a point which, he afterwards related, brought tears to Churchill's eyes.

Another considerable adversary was the Colonial Office itself which supported the claims of the Chartered Company directors who were naturally anxious to obtain the greatest financial compensation possible. The Company had claimed the sum of £7 500 000 as the accumulated deficits incurred in the administration of both Southern and Northern Rhodesia on the assumption that if Southern Rhodesia became self-governing. Northern Rhodesia would pass to the control of the Colonial Office. But the Cave Commission had reported that if the Company's administration had been terminated on March 31, 1918, it would be entitled to £4 350 000 by way of reimbursement. It made no mention of who was responsible for the interest on this sum from March, 1918, onwards. The South African Government, on the other hand, was prepared to pay close on £7 000 000 for the Company's rights in Southern Rhodesia alone (apart from the mineral rights), so that the Company's support for Rhodesia's entry into the Union was understandable. If the decision went against them and Rhodesia was granted Responsible Government, on the other hand, the Company demanded protection against legislation affecting their ownership of the mineral rights and their control of the railways.

The Rhodesian delegation consisted of Sir Charles Coghlan, Mr. W. M. Leggate, Mr. John McChlery, all advocates of Responsible Government, and Mr. R. A. Fletcher, a protagonist of Union. All of them played a worthy part, but the main burden of handling the people's case fell on Coghlan because he knew the legal and constitutional aspects better than his colleagues. He was a very tired man when he returned home to Bulawayo at the end of the year.

Britain's terms for a Responsible Government Constitution were published on January 19, 1922. They covered the Letters Patent and the Draft Order in Council as well as the Constitution. The Order in Council annexed Southern Rhodesia to the Crown and the Constitution provided that certain classes of legislation would be reserved for the Secretary of State's approval. The reservations covered,

•Any law affecting the railways, whose position was protected.

•Any law, save in respect of the supply of arms, ammunition and liquor to natives, whereby natives may be subject, or made liable, to any conditions, disabilities or restrictions to which Europeans were not also subject.

•The Chief Native Commissioner and officials of the

Native Department would be appointed by the Governor with the approval of the British High Commissioner in South Africa. Lands set aside as Native Reserves would be preserved intact except in certain circumstances and then only in exchange for other suitable land.

The main bone of contention, the disposal of the un-alienated land, was to be handled by a Crown Land Agent, assisted by an Advisory Board, who was empowered to dispose of the land at fair and reasonable prices, "the revenue derived therefrom being paid to the B.S.A. Company so long as any part of the debt due to the Company on account of administrative deficits remains unpaid".

Winston Churchill thought all this was a "very fair deal". The Letters Patent, he said, would "confer on the people of Southern Rhodesia a full and satisfactory control of their government and administration, subject only to the reservations imposed by the peculiar history of the country. They embody a policy which, if the people of Southern Rhodesia decide ultimately to adopt it. His Majesty's Government would be ready to carry out".

There was, however, an alternative policy, that of entry into the Union of South Africa, and this the people of Southern Rhodesia would also have to consider. "Since the South Africa Act has not defined the conditions of entry it is my intention that a delegation should be appointed to confer with General Smuts to ascertain the exact terms on which Southern Rhodesia can enter the Union".

When these terms had been ascertained and sufficient time had been allowed for the alternative policies to be debated, the voters would decide the issue by means of a referendum. The date of the referendum was fixed for Friday, October 27 1922.

The delegation to interview General Smuts was announced at the end of February, 1922. Led by the Administrator, Sir Drummond Chaplin, it consisted of five members of the Legislative Council (Sir Charles Coghlan, Mr. W. M. Leggate, Mrs. Ethel Tawse Jollie, Mr. R. D. Gilchrist and Mr. John Stewart), five members of the Rhodesian Union Association (Mr. H. T. Longden, Colonel Sir Raleigh Grey, Mr. R. G. Garvin, Sir Bouchier Wrey and Mr. J. G. McDonald) and two members of the Northern Rhodesia Advisory Council, Sir Randolph Baker and Mr. L. F. (later Sir Leopold) Moore. They went to Cape Town at the end of March and the conference with Smuts and his Cabinet was held during the first two weeks of April. The proceedings were held in the strictest confidence and it was not until August 1, 1922, that an impatient public learnt of the Union's terms. They covered a wide field.

Southern Rhodesia would be entitled to a minimum of 10 members of the Union House of Assembly based on its European male adult population, which then stood at 12 085. As the population increased so would the representation up to a maximum of 17 members. Similarly in the Senate, Rhodesia would start off with five members, rising to 10 as the number of Assembly Members increased. A Rhodesian Provincial Council of 20 members would be established, with an Executive Committee of four, and the Administrator would be a Rhodesian resident.

The Union Government would contribute a subsidy to Provincial funds equal to half of Rhodesia's existing expenditure, and during the first 10 years not less than £500 000 would be spent annually on railway construction, irrigation, land settlement, public works and the improvement of communications. The Rhodes Clause, granting preferences to British goods, would disappear from the Customs tariff", but in return the Union Government would pay a special subsidy of £50 000 to Rhodesian Provincial funds for 10 years.

Since the figure of nearly £7 000 000 offered to the Chartered Company included the railways, the Union Government would take over the whole of the Rhodesia Railways system, and the rates and tariff's in force in the Union would be extended to Rhodesia. The price also included the unalienated land, over 40 million acres, and this would be thrown open for settlement under the control of a Land Board of Rhodesians situated in Rhodesia. The operations of the Union Land Bank would be extended to Rhodesian farmers.

The existing rights of civil servants, the police and the railway employees would be secured, the Native Reserves would be respected and no Rhodesian natives would be recruited for employment in the Union. There would be equality of language rights for English and Dutch (Afrikaans) as in the Union.railway employees would be secured, the Native Reserves would be respected and no Rhodesian natives would be recruited for employment in the Union. There would be equality of language rights for English and Dutch (Afrikaans) as in the Union.

On the whole these were generous terms and they considerably heartened the protagonists of Union. Many of the country's most prominent citizens were members of the Rhodesian Union Association, such as M. E. Cleveland, George Johnson, E. Lucas Guest (Coghlan's partner in the legal firm of Coghlan, Welsh and Guest), H. L. Lezard, R. A. Fletcher and C. S. Jobling, with H. T. Longden as chairman, and they were all active campaigners. They stressed the economic advantages of entry into the Union—the immediate injection of development capital, the accessibility of new markets, the creation of a greater and more prosperous Southern African state within the British Empire, in line with Rhodes's dream. They played down the bilingual aspect. Natal, the nearest equivalent to Rhodesia, had had no cause to regret joining the other three States in forming the Union— its English-speaking civil servants had been fairly treated, it was still predominantly English-speaking, and its resources had been greatly developed. Rhodesia should follow Natal's example.

Salisbury and Bulawayo, made no secret of their wholehearted support of Union. Although in their news columns they were scrupulously fair in maintaining a balance between the two sides, m their leader columns the two editors hammered home every point they could think of to prove the advantages of Union as compared with the niggardly terms on which Britain was prepared to grant Responsible Government. Their support was a powerful factor, offset only by the brave little Umtali Advertiser, a one-man weekly, which espoused the Responsible Government cause. The odds against Charles Coghlan and his colleagues were enormous.

But they were undeterred. They threw themselves into the campaign without thought for health or comfort. They addressed public meetings up and down the country, at little villages as well as in the larger centres, at wayside halts, at gatherings anywhere to get their message across to the voters. Travelling conditions in those days were appalling as compared with the standards of today. There were no broad, smooth highways, only rutted, potholed, dusty tracks. There were few motorcars so that outside places off the line of rail could only be reached by carts drawn by horses and mules. There were no bridges, and when it rained they were held up by flooded rivers or sank axle-deep in mud. When they travelled by train it was usually a goods train, and they often slept in "wretched wayside shanties", as Coghlan described them. The physical strain was tremendous, but they did not spare themselves.

Coghlan and his supporters were not hostile to the Union as such. Indeed, as he had done at the National Convention 12 years before, Coghlan believed that Rhodesia's ultimate destiny was to become a part of the Union, but only after a period of self-government when the country would be in a better position to dictate terms. Their immediate objective must be self-government, and so the Responsible Government campaigners pulled out all the stops to carry the public with them.

They appealed to the patriotic instincts of the average Rhodesian, the importance of maintaining their British character, of preserving their British heritage, of keeping English supreme as the sole national tongue. They pointed to the dangers of bilingualism if they entered the Union, of the country being swamped by Afrikaans-speaking South Africans, of Rhodesia being totally absorbed by their more powerful neighbour. They urged Rhodesians to stand on their own feet, to prove to the world that they were capable of managing their own affairs. Their rallying cry, "Rhodesia for the Rhodesians, Rhodesia for the Empire", had a powerful appeal, and everywhere they met with an enthusiastic response.

Public feeling ran high. Some of the meetings addressed by Unionist speakers were unruly. At Bulawayo a crowd urged that they should burn down the Chronicle office because of its support of Union and was only deterred by the Chronicle's manager who was on the platform and pointed out that he was a strong supporter of Responsible Government. At Gatooma a Unionist meeting on the eve of the referendum was disrupted by a "disgraceful exhibition of organised hooliganism as the chairman was defied and the speakers prevented from speaking by catcalls and rowdiness", as a reporter described the scene. The whole affair, he added, "will certainly not help the R. G. cause or add to the reputation of Gatooma".

One does know about the reputation of Gatooma, but the R. G. cause did not suffer. The voters went to the poll on October 27 and when the result was announced on November 6 it gave Responsible Government a decisive majority. It was the heaviest poll yet held in Rhodesia, with 14 856 votes being cast out of a possible 18 810. Responsible Government received 8 774 and the Unionists 5 989, a majority of 2 785. Twelve out of the 13 electoral divisions in the country returned a majority in favour of R. G., and in the 13th (Marandellas) the Unionists won by a majority of only 10 votes. It was an exact reflection of the 1920 general election.

The result was received with great enthusiasm throughout the country, and at Bulawayo a carnival was held that went on until the early hours of the morning. Coghlan was the hero of the hour, and when he addressed the revellers he told them that he had been assured by several prominent Unionists that now that the people had decided the issue they would accept the result and work wholeheartedly to make it a success. He appealed to all Rhodesians to bury their differences and work together for Rhodesia and for the Empire, for their King and for their flag, in all friendship with their friends in South Africa, without distinction of race or creed. (Loud applause).

But the fervour died down as it became evident that there would be some delay before Responsible Government could be introduced. British politics were in a state of upheaval. Lloyd George's ministry had resigned and been followed by a Unionist ministry under Bonar Law, and now there would have to be a general election, which meant that decisions on Rhodesia would have to wait a while. The Colonial Office was still haggling with the Chartered Company over the terms of settlement and it delayed issuing the new Constitution, but the Government finally announced that it would be introduced on October 1, 1923—almost a year after the Referendum.

On July 11 the British Government announced that on October 1 it would pay the Chartered Company the sum of £3 750 000 in full settlement of its accumulated deficits. The un-alienated land, with public buildings and works, would become the property of the people provided the new Government paid the Imperial Government the sum of £2 000 000 not later than January 1, 1924, together with interest at five per cent from October 1. Rhodesia was also required to repay two loans of £150 000 each advanced by Britain in 1922 and 1923. So the new Government was saddled with a heavy debt right from the start and gained little from its patriotism.

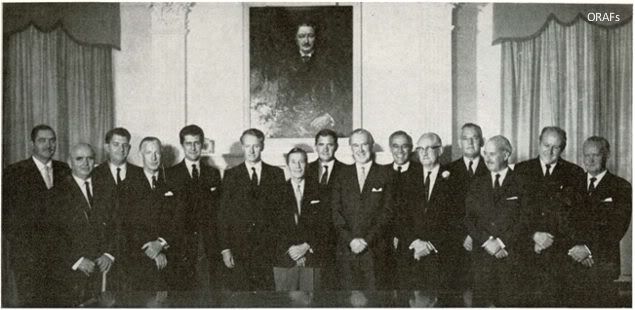

FIRST LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY, 1924

Left to right (sitting): Sir E. Montagu; W. M. Leggate; H. U. Moffat; P. D. L. Fynn; Sir C. Coghlan; L. Cripps (Speaker); Sir F. Newton: R. L. Hudson; C. Eickhoff; Mrs. E. Tawse-Jollie; J. W. Downie.

(Standing): C. C. D. Ferris (Clerk Assistant); Col. D. C. Munro; Col. C. F. Birney; Col. O. C. du Port; A. R. Thomson; G. F. Elcombe; J. Jearey (Clerk of the House); W. J. Boggle; H. Bertin; F. L. Hadfield; M. Danziger; R. A. Fletcher.

(Back row): R. D. Gilchrist; J. Martin; C. E. Gilflllan; G. M. Huggins; J. Murdoch Eaton; J. Cowden; L. K. Robinson; H. R. Barbour; E. Edwards (Press); Lewis (Hansard), A. Drew (Clerk); H. Hawtin (Hansard)

Inset: J. P. Richardson and F. P. Mennell.

It was essentially patriotism that had determined the referendum result. As the London Times said at the time: "It is abundantly clear that sentiment has been a great factor indeciding the issue. Over and above the argument that responsibility for the Union's liabilities would more than counterbalance any benefit from the Union's assets, far beyond practical considerations, lies the fervent desire of an essentially British people to remain British". The people of Rhodesia paid a high price to stay British.

The terms of the new Constitution were published on September 24, 1923, and five days later the first Governor of the Colony of Southern Rhodesia arrived in the person of Sir John Chancellor. On assuming office he read a message from King George V: "I have watched with interest and pride the rapid advancement of Southern Rhodesia during the period covered by a single generation which has elapsed since the country was placed under the protection of the British Crown. In that period, under the guidance of the British South Africa Company and a succession of distinguished Administrators, great and striking results have been achieved, and on this day when the Company relinquishes its powers of government, it is right and proper that fitting acknowledgment of the remarkable progress that has been achieved should be rendered to the Company and to its Founder, the illustrious statesman whose memory is enshrined in the country's name.

"The new Constitution imposes wide responsibilities on those who henceforward will guide the destinies of the country. I am confident that those responsibilities will be discharged both in the same spirit of loyal devotion to the Throne so consistently manifested in the past and with unflagging determination to promote to the utmost the social and material welfare of all classes and sections of the population".

Sir John himself made a resounding speech that exactly suited the occasion. "When one remembers the sufferings and hardships endured by the early pioneers, their victories over savage tribes, fighting against overwhelming odds and their struggles with the untamed forces of nature, when one remembers the vicissitudes the country has undergone owing to wars, drought and disease, one marvels at what has been achieved by men of British race under the inspiration of that great Englishman and empire builder, Cecil Rhodes.

The people of Rhodesia were given a choice between establishing a government of their own or joining the Union. Having regard to all the heavy responsibilities and liabilities that will be thrown upon a small community of British race living alongside a large African population who know little of Western civilisation, they might well have adopted the safer course. But no one who knows anything of Rhodesians and of the sustained courage with which they confronted the difficulties that stood in their path in the past has been surprised that they decided to face the risks and have a government of their own.

"We must advance with prudence and caution. We may hitch our wagon to a star, but we must not fail to see that we plant our feet on solid ground and not, through star-gazing, fall over the precipice".

Sir John lost no time in inviting Sir Charles Coghlan to accept the office of Premier of Southern Rhodesia and to form a ministry. On Monday, October 1, 1923, he was sworn in as Premier and Minister of Native Affairs. His Cabinet consisted of tried and trusted colleagues who had borne the brunt of the battle with him. It is as well that the modern Rhodesian should know something of the cahbre of these men who launched the frail Rhodesian canoe on the stormy sea of self-government. There were five of them apart from Coghlan, whose background has already been sketched and who was generally recognised as the man best fitted to be Rhodesia's political leader. They were:

Treasurer. P. D. L. (later Sir Percy) Fynn. Member of an old Cape family that had been continuously associated with the public service of South Africa for more than a century. Born in the Transkei in 1872. The Fynn family was closely associated with the founding of Southern Rhodesia and P. D. L. transferred from the Cape Colony service to the Southern Rhodesia service under the B.S.A. Company in 1896. He held various appointments in the Treasury until he succeeded Sir Francis Newton as Treasurer in 1919.

Minister of Agriculture and Lands. W. M. Leggate. Born in Lanarkshire, Scotland, in 1879. Served with the British Army in the Boer War and after the war entered Edinburgh University and took an honours degree in economics, in which he was a double Medalist. Came to Rhodesia in 1911 and started ranching and farming in the Hartley district. He took an active interest in politics and was an ardent supporter of Responsible Government. He had weak lungs and spoke in a rasping whisper, but that whisper could reverberate round a hall.

Minister of Mines and Works. H. U. Moffat. Grandson of Dr. Robert Moffat, the famous missionary, and son of Dr. John Smith Moffat, who was the first missionary at Inyati in 1859 and British representative with Lobengula from 1885 to 1891. Born at Kuruman in 1869 and educated at St. Andrews College, Grahamstown, he entered the service of the Bechulanaland Exploration Company in 1893. He came to Bulawayo with the Southern Column during the Matabele War and settled in Bulawayo to represent his company. He served in the Matabele Rebellion of 1896 and in the Boer War with the Rhodesian Field Force and was present at the relief of Mafeking. He subsequently played a prominent part in Southern Rhodesian affairs, as General Manager of his company, as a director of several big mining companies, as chairman of the Cattle Owners' Association and a member of the Chamber of Mines.

Attorney-General and Minister of Defence. Major R. J. Hudson, M.C. Born in 1885 at Mossel Bay, Cape, he studied law at Cambridge University and was admitted as an advocate of the High Court of Southern Rhodesia in 1910. He practised at Bulawayo. He served in the First World War in German South West Africa and in France, and was with the Royal Flying Corps from 1915 to 1919. He was awarded the Military Cross in 1916.

Colonial Secretary. (Minister of Internal Affairs). Sir Francis Newton. Born in the West Indies in 1857 and educated at Oxford, he qualified as a barrister-at-law of the Inner Temple. He arrived in South Africa in 1881 as ADC, and later became private secretary to the Governor of the Cape, Sir Hercules Robinson. In 1893 he was appointed Colonial Secretary and Treasurer of British Bechuanaland and for two years (1895 to 1897) was Resident Commissioner of Bechuanaland with headquarters at Mafeking. He was caught up in the Jameson Raid and in 1897 was transferred as Colonial Secretary to British Honduras, and after two years served in a similar capacity at Barbados.

In 1903 he returned to Southern Africa as Treasurer of the B.S.A. Company's administration in Salisbury, and he occupied that position for 15 years. He ran his department so well that when he retired in 1919 he was awarded the K.C.M.G. After his retirement he entered politics as a champion of responsible government and took an active part in the 1922 referendum campaign.

These men were all well suited to their new responsibilities. It was they Sir John Chancellor had in mind when he advised them to plant their feet on solid ground and not, through star-gazing, fall over the precipice.

CHRONOLOGICAL MAP OF THE CONSTRUCTION OF THE RHODESIA RAILWAYS

DURING THE FIFTY YEARS BETWEEN 1923 AND 1973 the following extensions to the railway system in Rhodesia were constructed: 1928 Somabula to Shabani, 1930 Sinoia to Zawi and Maryland Junction to Kildonan, 1955 Bannockburn to Malvernia to link up with the Portuguese line to Lourenco Marques, 1957 first tunnel near Wankie and new station on Wankie avoiding line, 1964 Mbizi to Chiredzi, 1965 Chiredzi to Nandi. In 1947 the Southern Rhodesia Government purchased Rhodesia Railways Limited for £19 000 000.

TACKLING THE PROBLEMS

THE total European population of Southern Rhodesia at the time of the Referendum was just under 35 000. The census of 1921 produced a figure of 33 620, of whom 18 987 were males and 14 633 were females. South Africa was the birth place of 11 634 of them (34,60 per cent) and the United Kingdom of 10 544 (31,36 per cent). The Rhodesian born numbered 8 308. The total population of all races was 899 187, of whom 96 per cent were Africans and 3,74 per cent were Europeans.

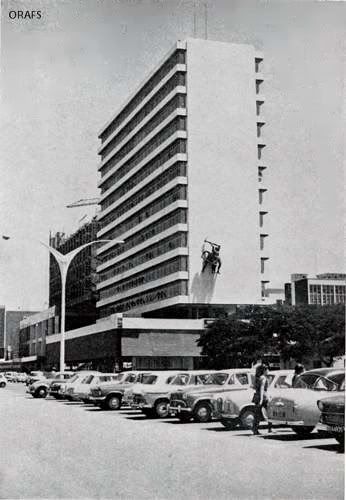

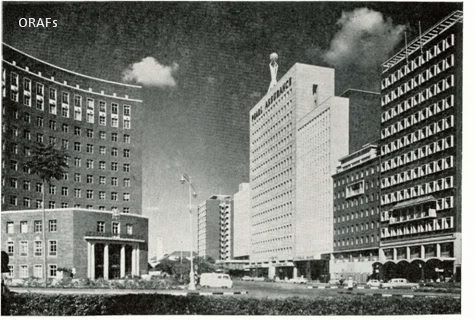

Bulawayo was the largest town, with a European population in 1923 of 16 363, and a rateable value of £2 440 027. Salisbury had 6 462 Europeans and a rateable value of £2 078 823. There were 1 874 Europeans in Umtali and 1 100 in Gwelo. These four centres were municipalities. There were Sanitary Boards at Fort Victoria, Que Que and Umvuma, which was then of some importance owing to the Falcon mine. The affairs of all other centres in the country were handled by Village Management Boards.

Education was reasonably well developed considering the size of the population and the meagre resources available. In the middle of 1922 there were 5 837 European pupils and 250 teachers, and 51 817 African children were also attending school. Secondary education was provided at the main centres. Salisbury had the Boys' High and the Girls' High, each with boarding accommodation, Bulawayo had Milton School for boys and Eveline School for girls, Umtali had its high school for both sexes and so did Gwelo with Chaplin. There were primary schools with boarding facilities for boys and girls at Sinoia, Enkeldoorn and Hartley and schools without boarding accommodation at other smaller centres. In addition, there were four primary schools going up to Standard IV in Bulawayo suburbs and three in the suburbs of Salisbury.

So the towns were well enough catered for, but what of the vast rural areas where children lived on lonely farms and mines and could not reach the towns? This problem was overcome in two ways. In areas where there were fewer than ten children requiring primary education the parents joined forces and engaged a governess with Government aid. These were known as "private governess schools" and there were 45 of them at the end of 1923. Where ten or more children could be gathered together farm schools were established, with a certificated teacher paid for by the Government in charge and with the parents providing the buildings and furniture. There were 50 of these schools at the end of 1923, and some notable Rhodesians i received their first elements of education at them.

A start had also been made on specialised education with the opening of the Matopos School in January, 1923, to give boys a good general education up to Standard VII as well as training in agriculture and general farming practices. And at Plumtree a famous Rhodesian educational institution had come into being with a boarding school for boys above Standard III.

The health services catered mainly for the European population. Bulawayo had 14 doctors, Salisbury had 12, there were two each at Gwelo, Shabani, Gatooma, Umtali, Mount Selinda and Shamva, and one each at the other smaller centres, a total of 57, including doctors at mission hospitals.

Southern Rhodesia had suffered a heavy drought in the 1921/22 season, followed by the most torrential rains recorded for several years in 1922/23. The maize crop took a hammering in both years and this was a serious matter for maize was the principal agricultural crop, accounting for 83 per cent of the total cultivated area. So severe was the setback that there was serious unemployment and the Administration found it necessary to warn intending immigrants that unless they had adequate capital or proof of definite employment to come to they would not be allowed to enter the country.

In 1923 the maize crop amounted to 1 505 580 bags, an average of 6,8 bags to the acre. Tobacco production had also suffered from the heavy rains and from disease, and in 1923 production was 2 540 942 lbs of Virginia leaf and 269 839 lbs of Turkish.

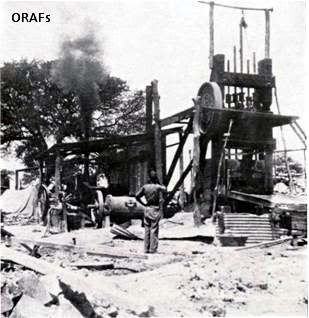

But the mining industry was in good heart. Gold was by far the most important mineral. In 1923 there were over 400 small workers, a fiercely independent breed that has largely died out today, who produced about 30 per cent of the total output. The output in 1923 amounted to 647 491 ozs valued at nearly three million pounds. The total production of gold from 1890 to 1923 was estimated to be worth over £57 millions.

Second in importance was chrome, followed by copper (almost all produced by the Falcon Mine at Umvuma), asbestos and coal.

Total exports in 1923 amounted to £5 368 994, a rise of over £1 million as compared with the previous year, so that the country was reasonably prosperous. Income tax was no hardship—a shilhng in the pound up to £500 of the taxable amount; over £500 the rate "was increased in respect of the whole amount by a penny in the pound for every £200 or part thereof in excess of £500 up to a maximum of 3/- in the pound. Married taxpayers received an abatement of £1 000, and single persons £500, with £50 for each child under 18 and £50 for each dependent.

Prices, too, were reasonable. In their summer sale for Christmas, 1923, Haddon and Sly offered "dainty nightdresses" at 9/6, evening dresses at 9 guineas and corsets from 12/6 upwards. You could get a new bicycle for 30/-, novels ranged from 2/9 to 7/6 each, with paperbacks at 9d, and you could travel from Cape Town to London, first class, by ship for £40 single and £72 return. If you decided to have Christmas dinner at Meikle's Hotel it would have cost you 12/6.

But perhaps the biggest contrast between then and now was in road conditions. An excited correspondent at Chipinga reported in 1923 that the new Native Commissioner travelled from Umtali to Tanganda by car—about 150 miles—in eight hours. The new Sabi road was in excellent condition "and in many places a speed of 30 miles per hour could be maintained for considerable distances".

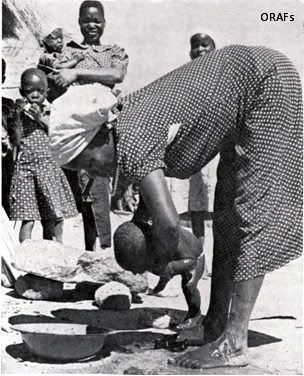

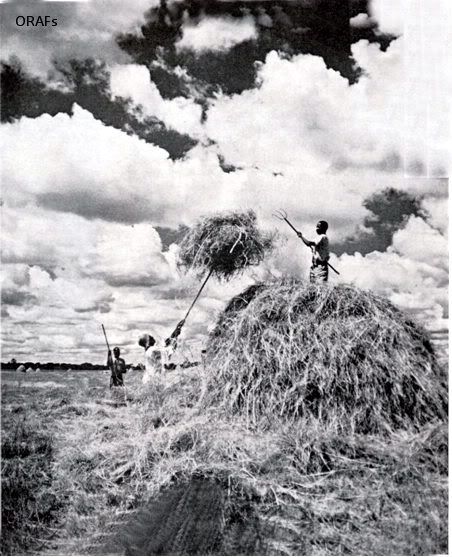

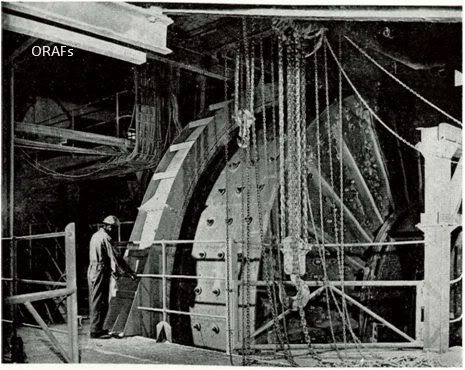

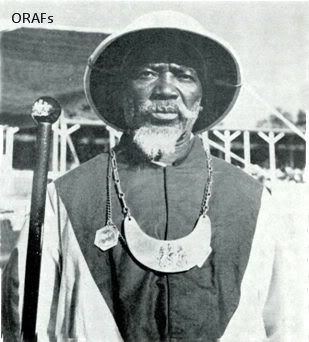

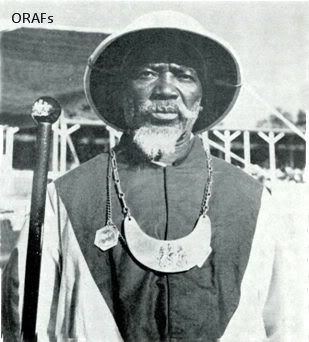

Caption

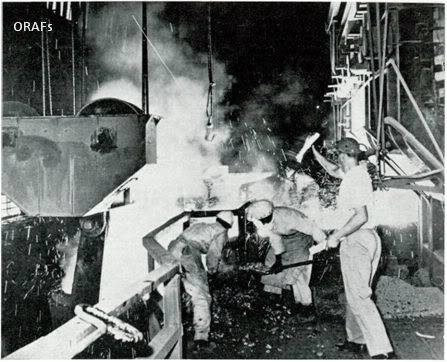

In 1923 there were over 400 small workers,a fiercely independent breed that has largely

died out today,who produced about 30 per centof the total output of gold, which that year

amounted to nearly three million pounds.

In 1923 there were over 400 small workers,a fiercely independent breed that has largely

died out today,who produced about 30 per centof the total output of gold, which that year

amounted to nearly three million pounds.

And that was worth reporting when you consider that for the most part Rhodesia's roads in those days were tracks worn by ox-wagons, with a deep rut on either side and a razor back in the middle. When travelling, the motorist carried a pick and shovel to trim down the razor back when it was too high for clearance, a couple of sacks to cope with sand, and a supply of water, food and drink. The popular car was the Model T Ford, with two forward gears and a reverse gear and the petrol supplied from the tank to the carburettor by gravity feed. It could not climb steep hills in forward gear because the gravity feed was ineffective when the carburettor was higher than the tank, so the car had to be turned around—often by all in it man-handling it round in the narrow track—and driven upwards in reverse. And if you got stuck behind an ox-wagon you crawled forward in a cloud of dust.

That, very broadly, was the state of the country when Sir Charles Coghlan and his colleagues took charge on October 1, 1923. They devoted their first six months to getting their departments organised, for there was not much else they could do pending a general election in April, 1924, to elect the first Parliament of Southern Rhodesia. Coghlan was now approaching 60 and had an ailing heart which had suffered under the strain of the Referendum campaign. But he did not count the cost to himself and as leader of the Rhodesia Party (as the Responsible Government Party was now called) he threw himself into the election campaign. He and his Ministers travelled day and night to all parts of the country, addressing two and sometimes three meetings in a day. It was all very exhausting, but it was worth it. The Rhodesia Party won 26 out of 30 seats, the other four going to Independents, so now they were firmly in the saddle. To crown his triumph, Coghlan was shortly afterwards awarded the K.C.M.G.

With the growth of confidence the country's economy took an upward turn, and the increasing prosperity was reflected in annual surpluses that enabled more money to be spent on aspects of development that had been sadly neglected m the past, particularly in regard to roads and bridges. Rhodesia's reputation on the London money market improved (in 1927 a £1 million loan was fully subscribed in five hours), immigrants arrived in increasing numbers and there was expansion in all directions.

One of Coghlan's first acts after the general election of 1924 was to establish the Land and Agricultural Bank to provide easier credit facilities for farmers, who had been hard hit by a series of adverse seasons and by low prices for their products. The beef industry was stimulated by the Imperial Cold Storage Company being granted a monopoly in the establishment of abattoirs and refrigeration works in return for slaughtering at least 20 000 head of cattle a year. And in 1926, with the passing of the Defence Act, the Colony's military forces were reorganized, with separate territorial and permanent staff sections.

But the main problem was the railways. This was the most vital factor of all in determining the cost of living. The Chartered Company controlled the rates and benefited from the increased trade, yet still quibbled about paying income tax. It was essential that the Government should have a greater say, and a commission of enquiry was appointed to investigate the position. This led to a conference on the railways being held in London in the middle of 1926 and it was attended by Coghlan, H. U. Moffat and J. W. Downie. A satisfactory agreement was reached which gave the Government a greater say in policy, the fixing of rates and the creation of a reserve fund.

On their return Coghlan's main task was to pilot a Railway Bill through the Legislative Assembly giving effect to the London agreement. The session was held in December, at the hottest time of the year, in a small, crowded, stuffy chamber in which the heat at times was almost unbearable.

In those days, and for many years afterwards, the Legislative chamber was a single-storey room (the Treasury occupied the upper floor), air-conditioning had not been heard of, and the only ventilation was through the open windows. That is, when there was a breeze. When there was no breeze the members sweltered, the air was inert and somnolence could readily be excused. In this stifling atmosphere Coghlan, who was in charge of the measure, had to endure many weary hours of debate and he was a very tired man when at last the Bill was passed and a Railway Commission was established representing the principal users of Southern Rhodesia, Northern Rhodesia and Bechuanaland.

During this session Coghlan learnt that popularity often exacts a heavy price. Dissident elements in his party were jealous of the domination he had exercised for so long, and they were making his life difficult. Coghlan had always subordinated his personal interest to what he regarded as the national interest, and the knowledge that some of his so-called supporters did not have the same scruples worried and distressed him. In his weakened physical condition he found their strictures hard to bear. During this time he often expressed a desire to return to private life, but his sense of duty kept him to the task. His doctor was worried about his blood pressure and advised him to take things more easily. Coghlan himself realised that he could not stand the strain much longer and contemplated giving up after the general election due in May, 1929. But the decision was made for him long before then.

The session that ended in July, 1927, was his last. During it he had seen the recalcitrants form themselves into an opposition called the Progressive Party. As the House rose Coghlan collapsed and had to take to his bed for nearly three weeks. He recovered sufficiently to be able to welcome the Secretary of State for the Dominions, Mr. L. M. S. Amery, at Salisbury station in the middle of July and to have discussions with him the following week, and that was almost his last official task. On Sunday, August 28, he corrected the proofs of a circular to Salisbury voters and also gave an interview to a newspaper reporter. He looked pale and tired, and in the course of the interview referred to the hard knocks he had encountered in politics, particularly during the past few months. One sentence stuck in the reporter's mind. "There is one thing I have always endeavoured to do—my duty to my country to the best of my ability and according to my lights". It was Coghlan's epitaph. Later in the day he attended Mass at the Roman Catholic Cathedral (he was a devout churchman) and when he got home he collapsed. Only two members of his Cabinet were in Salisbury at the time, H. U. Moffat and W. M. Leggate, and they were at his bedside when he died.

Although he was known to be ailing, few had known just how ill he was and his death came as a profound shock to the whole country. He was buried on the Tuesday in the cemetery at Bulawayo, and later the Bulawayo Town Council petitioned the Governor to have his remains interred at View of the World in the Matopos, with Cecil Rhodes, Starr Jameson and the men of the Shangani Patrol, as one who had "deserved well of his country". The consent of Parliament was necessary and this was given at the following session. On August 14, 1930, in the presence of thousands of people from all over Rhodesia, his coffin was lowered into its rocky tomb a short distance down the hill from the others.

And so passed a truly great Rhodesian, who had given himself unsparingly in the service of his country and his fellows. In his public life he had always been effective, in spite of a somewhat ponderous delivery, because of his sincerity and mastery of his subject. His swift, sure penetration of an argument, his grasp of essentials, his unfaltering memory and polemical skill, and above all his high moral standards, were his main assets.

Rhodesia was the poorer for his passing.

SECOND LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY, 1929

Front row, left to right: Capt. H. Berlin; H. H. Davies; Maj. the Hon. R. J. Hudson; The Hon. J. W. Downie; The Hon. H. U. Moffat; The Hon. L. Cripps (Speaker); The Hon. P. D. L. Fynn; The Hon. W. M. Leggate; The Hon. R. A. Fletcher; C. Eickhoff (Deputy Speaker). Second row: B. Munsen (Chief Messenger); R. D. Gilchrist; D. MacGillivray; G. Mitchell; Maj. E. L. Guest; J. Murdoch Eaton; C. C. D. Ferris (Clerk Assistant); R. V. Gorle, V.C. (Serjeant-at-Arms); J. G. Jearey (Clerk of the House); C. S. Jobling; G. R. Milne; M. D. Claxton; J. L. Martin; Capt. R. E. Downes; J. Cowden.

Back row: J. H. Malcolm; A. R. Welsh; G. M. Huggins; G. Munro; Miss K. M. Davidson (the late Mrs. W. D. Gale) (Assistant Librarian); Capt. L. L. Green; M. Danziger; S. M. L. O'Keeffe; L. J. W. Keller.

Inset: Col. A. J. Taylor; A. R. Thomson.

DISPOSING OF THE LAND

DISPOSITION of the unalienated land was one of the most urgent problems facing the first administration, and Coghlan had given it a lot of thought. The position as at March 31, 1924, was that, of Southern Rhodesia's 96 million acres (38 492 000 ha) approximately 51 million acres (20 million ha) had been alienated to companies and individuals or set aside as native reserves, and 45 million acres (18 million ha) remained unalienated. Of this, 15 million acres (6 million ha) were available for settlement. To encourage land settlement land was made available at an average price of 5s per acre, plus a quitrent of Is per unit of 50 acres payable to the Government.

But it was the broader question of the equitable division of the land between Africans and Europeans that engaged Coghlan's attention. He had always believed that the two races should live their separate lives in their own areas. Under the 1920 Order in Council just over 21 million acres (8 451 000 ha) were set aside as Native Reserves and these were confirmed in the 1923 Constitution. Africans were also given equal rights with Europeans to acquire land outside the Reserves, but Coghlan felt that this was undesirable and would lead to friction if Africans bought land in European farming areas. Would it not be better to set aside entirely separate areas for occupation by Europeans and Africans in which the danger of racial competition would be avoided ?

This was too big a principle for the fledging Government to determine on its own authority, and in 1925 Coghlan set up the Southern Rhodesian Land Commission with Sir William Morris Carter as chairman. It took a year to consider the matter, and its report showed that it agreed with Coghlan's thinking. It gave some cogent reasons for its recommendation that separate areas should be established.

"The evidence which has been given leaves no doubt as to the wishes of all classes of the inhabitants ... and we have no hesitation in finding that an overwhelming majority of those who understand the question are in favour of the establishment of separate areas in which each of the two races, black and white, should be permitted to acquire interests in land. The Natives realize the growing difficulty of obtaining land in competition with the whites.

"However desirable it may be that members of the two races should live together side by side with equal rights as regards the holding of land, we are convinced that in practice, probably for generations to come, such a policy is not practicable or in the best interests of the two races. Until the Native has advanced very much further on the paths of civilization it is better that the points of contact in this respect between the two races should be reduced. A lengthy period should be afforded for the study of the whole question of the future relations between the two races in an atmosphere which is freed as far as possible from the setbacks which would ensue from the irritations and conflicts arising from the constant close proximity of members of races of different habits, ideals and outlook upon life".

Wise words, which apply as soundly to the position today as they did in 1926.

Coghlan died before he could introduce legislation to give effect to the commission's recommendations, and the responsibility fell on his successor, Mr. H. U. Moffat. In 1930 the first land Apportionment Act allocated 48 632 000 acres (19 452 800 ha) for European occupation and 29 197 000 acres (11 678 800 ha) for exclusive African use. A further 17 793 000 acres (7 117 200 ha) were left unassigned for future allocation and half a million acres was set aside as forest area This position held good until 1941 when the second Land Apportionment Act increased the African holding by some eight milHon acres in which Africans could acquire or lease land. In 1969 the Land Apportionment Act was repealed and replaced by the Land Tenure Act under which the land was almost equally divided between the races, with 45 million acres being allocated to African occupation, over 38 million acres for European use and the balance of some 12 million acres being assigned for national land, forest area and national parks.

For his first three years as Southern Rhodesia's Premier, Mr. Moffat continued on his placid way. He lacked Coghlan's drive and personality and as a popular leader he had little appeal. He was unimaginative and cautious, and he staunchly adhered to Sir John Chancellor's advice to keep his feet on soHd ground. But he was sound and he kept the country on its course of steady development. And then in 1931 he faced his first great crisis as Southern Rhodesia began to feel the impact of the Depression which had engulfed the more developed nations two years before. Export markets dried up, the country could no longer pay for its imports, development came to a standstill, unemployment was rife and managers as well as junior clerks suddenly found themselves out of work. The farming community was particularly hard hit. During his visit in 1926 Mr. Amery had promised that Britain would take all the tobacco and cotton they could produce and they had gone bald-headed into increased production. But Britain did not (or could not) keep her promise and the short-lived boom in these crops was followed by a slump. They were beginning to climb out of it when they were hit by the Depression and hundreds of them flocked into the towns for work. But there was no work.

The Government provided what employment it could by putting them to work on the roads for a few shillings a day, and for the first time in the country's history white men wielded picks and shovels. Then the Chief Roads Engineer, Mr. Chandler, had a briUiant idea. Instead of merely filling up potholes and trimming down the razor backs, why not lay two strips of concrete a car's width apart and do away with the dust nuisance? Mr. Moffat seized on the suggestion. Strip roads began to radiate from the main towns in all directions, concrete soon gave way to tar macadam, and within a few years motorists were able to travel from end to end of the country without hitting potholes or bogging down in sand. The strip roads were cheap to construct and effective in their purpose, and Rhodesia's pioneering effort in this direction aroused widespread interest in countries, such as New Zealand, with similar problems. At the same time rivers and drifts were spanned by low-level bridges which at least prevented sumps from being holed by rocks, though they were usually put out of action during the rains when the rivers came down in flood. The strip roads had their disadvantages, of course, such as razor-sharp edges being exposed as the outside gravel was worn away, which made getting on and off them a tricky business. But by and large they were a tremendous boon to the travelling public, and Mr. Chandler deserved the plaudits that were heaped on him.

The Depression had another result—it changed the course of the country's political history. In 1932 the Moffat Government introduced a measure to reduce civil service salaries by ten per cent to help the budget. In doing so it raised the ire of a Salisbury surgeon who was a Rhodesia Party backbencher noted for his trenchant criticisms of various aspects of Government poUcy. Mr. Godfrey Martin Huggins represented a civil service constituency in Salisbury and he strongly opposed the proposal. But he had no room for manoeuvre. Since a provision in the Constitution was involved it required a two-thirds majority to pass, and out of the 30 members the Government had 20 and the Opposition 10. Therefore every Government member had to support it. Defeat would have demanded the Government's resignation and Huggins was unwilling to precipitate a general election since one was due to be held in the ordinary course the following year. He announced that he would therefore vote for the measure and then would immediately resign from the Rhodesia Party and cross the floor. He did so the following day and became Leader of the Reform Party Opposition.

Mr. Moffat was a tired man. The strain of guiding the country through the Depression had exhausted him. But there was one last thing he wanted to do—get control of the mineral rights from the British South Africa Company. He addressed meetings up and down the country to counter the Opposition's arguments (a) that the Company did not own them and therefore could not sell them, (b) if the Company did own them it would hold the country to ransom by demanding too high a price. But it was clearly estabUshed that the Company did own the rights and the directors indicated that they had no intention of holding the country to ransom. In fact, they agreed that morally the rights belonged to the people. In 1933 they sold the mineral rights to the Government for two milhon pounds—one of the best investments ever made.

The Company's ownership of the railways was a different proposition. Southern Rhodesia was not the only party concerned, since the system traversed Bechuanaland and Northern Rhodesia also, and so the British Government was involved. The country had to wait until 1947 before it was able to purchase the Rhodesia Railways for £19 miUion, with the exception of the Umtah-Beira line which reverted to Portuguese ownership, in terms of the original agreement with the Portuguese Government, in 1949.

As the general election of 1933 approached, Mr. Moffat resigned to allow the Rhodesia Party to go to the country under a fresh leader. His successor was Mr. George Mitchell, hitherto Minister of Mines, who took office just as the Ministerial Titles Act was promulgated and so became the country's first Prime Minister. The election was held three months later and Mr. Huggins and his Reform Party were swept into power. Thus the Rhodesia Party Government bowed out, after giving Southern Rhodesia strong and stable administration during the first vital ten years of self-goverrmient. In no sense had it, through star-gazing, fallen over the precipice.

In his first year Mr. Huggins had considerable difficulty with a dissident group of Reform Party members. In 1934 he accepted an offer of support from the remnants of the Rhodesia Party and, with loyal followers in his own party, formed the United Party. In the subsequent election he was returned with an overwhelming majority, and he governed Southern Rhodesia ably and successfully for the next 20 years.

THIRD LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY, 1934

Front row, left to right: The Hon. C. S. Joblmg; The Hon. J. H. Smit; Capt. R. E. Downes; The Hon. L. Cripps (Speaker); The Hon. G. M. Huggins; The Hon. S. M. L. O'Keeffe; Capt. The Hon. W. S. Semor; The Hon. R. D. Gilchrist. Second row: Lt.-Col. E. L. Guest; H. H. Davies; D. Macintyre; J. G. Jearey (Clerk of the House); R. V. Gorle, V.C. (Serjeant-at-Arms);

Front row, left to right: The Hon. C. S. Joblmg; The Hon. J. H. Smit; Capt. R. E. Downes; The Hon. L. Cripps (Speaker); The Hon. G. M. Huggins; The Hon. S. M. L. O'Keeffe; Capt. The Hon. W. S. Semor; The Hon. R. D. Gilchrist. Second row: Lt.-Col. E. L. Guest; H. H. Davies; D. Macintyre; J. G. Jearey (Clerk of the House); R. V. Gorle, V.C. (Serjeant-at-Arms);

C. C. D. Ferns (Clerk Assistant); Maj. L. A. M. Hastmgs; Lt.-Col. J. B. Brady; The Hon. P. D. L. Fynn.

Third row: Maj. G. H. Walker; J. H. Malcolm; L. J. W. Keller; Lt.-Col. T. Nangle; Sir H. G. Williams; N. H. Wilson; R. H. B. Dickinson;

D. M. Somerville; W. A. E. Wmterton; R. A. Fletcher; C. W. H. Caple (Messenger).

Back row: F. D. Thompson. A. R. Thomson; A. R. Welsh; J. L. Martin; J. Cowden; E. W. L. Noakes; C. W. Leppington.

STEADY EXPANSION

THE six years following the election of the United Party Government saw steady expansion in every aspect of the economy. In agriculture perhaps the most notable feature was the development of the tobacco industry, which had taken a heavy knock in the 1926 slump and remained in the doldrums for some years afterwards. The Government took a hand in reconstructing the industry, but it is the growers themselves who deserve the credit for its reaching the heights it later achieved. The Rhodesia Tobacco Association got the growers efficiently organised, set up a research establishment manned by some of the best scientists in their field in the world and formed a selling organisation that introduced the Rhodesian Virginia product to countries all over the globe. The main market, however, was Britain and much of the Rhodesian production was geared to the requirements of the British manufacturer and the tastes of the British smoker. That, as later events proved with devastating clarity, was a mistake. But at the time it seemed the correct policy and it contributed greatly to the country's prosperity.

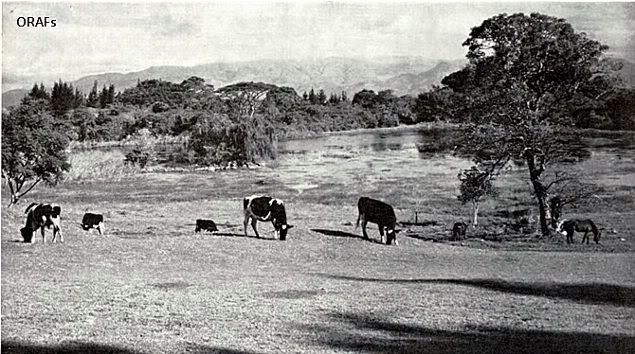

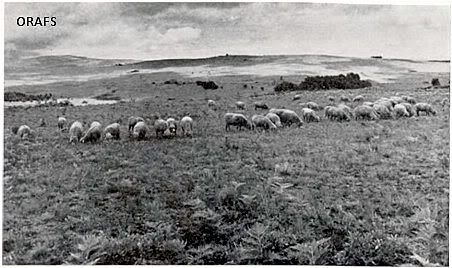

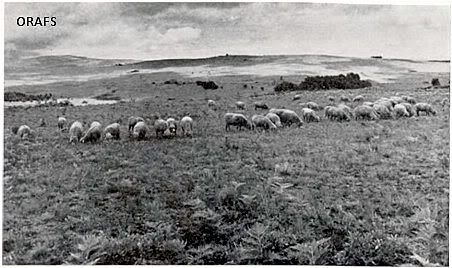

The cattle industry, also, was placed on a sounder footing. The Coghlan Government had granted a monopoly to the Rhodesian Export and Cold Storage Company, a subsidiary of the Imperial Cold Storage and Supply Company of South Africa, but private enterprise was unable to deal effectively with the problems of the cattle industry following the Depression, and so, in 1938, the Cold Storage Commission, a statutory body, took over the operations of the Export and Cold Storage Company and assumed sole responsibility for the marketing side of the cattle industry. During the subsequent years the Commission constructed a grid of abattoirs and meat works throughout the country which enabled the industry to meet the stringent hygiene standards of sophisticated importing countries in Europe and also to make the fullest use of by-products. The Commission is required to buy residual slaughter cattle at sales in the Tribal Trust Lands at minimum guaranteed prices, and has thus brought benefit to the African population. The stability and vigorous growth of the cattle industry of today is entirely due to the far-seeing step taken by the Huggins Government in 1938.

Another imaginative development was the setting up of the Electricity Supply Commission in 1937, the brain child of the then Minister of Mines, Captain W. S. Senior. Captain Senior was a mining man who realized the enormous value of electric power to mines and farms outside the range of the municipal power stations that served the main centres. Unfortunately, he did not live to see the E.S.C. develop beyond its infant stages, for he was killed in an air crash while piloting his own private aircraft. But he died knowing that he had created an invaluable stimulant to the development of his country.