P. S. GARLAKE

P.O. Box 3248, Bulawayo

P.O. Box 8006, Causeway, Salisbury

Published by The Historical Monuments Commission. P.O. Box 3248. Bulawayo, and printed by Mardon Printers (Pvt.) Ltd.. at their Belmont Factory. P.O. Box 8098. Belmont. Bulawayo. Rhodesia

Recompiled by Eddy Norris for use on ORAFs in May 2010

End of Page 4

IntroductionThe Eastern Highlands of Rhodesia, a mountainous backbone of rugged granite hills, deep gorges and numerous streams, rivers and waterfalls, contain some of the country's most beautiful scenery. Lying more than 1 500 m above sea level, they also enjoy a bracing climate. A magnet to the tourist today, with good, fast roads, hotels and many other amenities, yet not, one would think, an easy country in which one would choose to settle when in its original wild condition. On the other hand, for many people it would have provided an ideal area in which to retreat from the perils and bloodshed of rivalry for the areas of Rhodesia rich in game, agricultural land, and precious metals. Whatever the reason, this area contains relics not only of every period of man's existence in Rhodesia but also, from the later stages of prehistory, some of the most widespread and intensive occupation of any primitive community to be found anywhere in the world.

The Stone Age.Fifty thousand years ago man left his first traces in the area the crude, chipped stone tools of the "Sangoan period" of the Ear!y Stone Age, to be followed by the smaller, more varied, and finely made stone weapons and tools of the succeeding Middle and Late Stone Ages. Radiocarbon dating has shown that these span a period of 48 000 years, flourishing until the start of the Christian era. Despite their widespread presence in the Inyanga area however, these Stone Age sites arc of little interest to any but the true enthusiast and may safely be given only this brief mention — with one exception, the rock art.

Though Inyanga lacks the large, clear painted caves found elsewhere in Rhodesia, small, scattered scenes of animals and their hunters can be found throughout the granite hills between Rusape, Umtali and Inyanga, works of the last Late Stone Age peoples, who may well have survived the coming of more advanced people up till some 300 years ago. They were a people very like the Bushmen of today, so that the popular description — "Bushman

End of Page 5paintings" — is probably no misnomer. The cave on the farm

Diana's Vow contains a most complex painted scene and is described later. (Chap. 1.)

Quite different, artistically, are the small groups of

engravings: abstract motifs, mainly circles and dots, spirals and meanders, peeked into the flat surfaces of rocks. In Rhodesia, they seem to be largely confined to a few sites in the Eastern Highlands. They are not related to the Stone Age paintings and are most probably the work of a later people. Two small groups of these engravings occur in the Tsanga valley of the Inyanga Downs, but as they are on private, forested land and the roads are poor they are not described further.

The Iron Age and the Ruins.Two thousand years ago, the forerunners of a people with a more settled way of life started to infiltrate the country of these Stone Age hunting bands bringing with them domestic animals, cultivated crops and such equipment as pottery, iron tools and weapons. They were able to live as settled communities, and it is these people and their descendants who were responsible for the great number of prehistoric structures for which the Inyanga District is most famous.

The ruins of these were only discovered comparatively late in the opening up of Rhodesia. Soon after they were visited by two redoubtable and romantic German travellers,

Dr. Heinrich Schlichter in 1897 and

Dr. Carl Peters in 1900, who both proposed exotic theories of ancient Semitic origin.

R. N. Hall, Curator of Zimbabwe at the turn of the century, and the greatest advocate of grandiose antiquity to most Rhodesian ruins, correctly believed that they were different in style to and later than Zimbabwe and the many ruins of its type. He attributed them to "Arabs" of the eleventh or twelfth centuries from the East African metropoli of Mogadishu and Kilwa.

Dr. Randall Maclver, a professional archaeologist brought out by the Rhodes Trustees on a rapid tour of many Rhodesian ruins in 1905, used the logic of his comparatively new discipline in his book Mediaeval Rhodesia. Here he ascribed all the Rhodesian ruins to Bantu speaking peoples, living between the 13th and 17th centuries.

End of Page 6Bitter controversy between the disciples of Peters, Hall and MacIver continued until 1948 when the Inyanga Research Fund sponsored a series of excavations by

Roger Summers and

Keith Robinson. Their results were published in 1958 in Summers' monograph, Inyanga, Prehistoric Settlements in Southern Rhodesia. This is the last published work on the prehistory of the whole Inyanga area and this guide owes much to it. The subsequent work of

F. O. Bernhard has contributed much to the study of the earliest Iron Age peoples.

Study of the archaeologists' standbys — beads, pottery, bone and metal work — makes it quite clear that no site shows any exotic influence, let alone a single trace of occupation by an alien people. Indeed, the indications of even the slightest contact with more developed peoples arc so slight that the archaeologists have been forced to fall back largely on a study of the architecture and the techniques used in the stone buildings themselves to explain their origins and dates. As this is a study in which the visitor himself can join, it is used in some detail in this guide. If the romance of the early writers is forced to wither from lack of a single piece of supporting material evidence, the story that remains is still a complex one.

It is essential to realise that four distinct prehistoric Iron Age cultures have superseded one another within the bounds of the Inyanga district. Each culture is largely limited to its own distinctive area and is usually named after it. This is convenient also for this guide book as each chapter can deal with a separate culture. These are:—

1.

Ziwa. Fourth to eleventh century A.D. (Chap. 4.)

2.

Zimbabwe. A single ruin of a late Zimbabwe type is found on Harleigh Farm. Seventeenth century A.D. (Chap. 1.)

3. I

nyanga Uplands, sixteenth to seventeenth century A.D. (Chap. 2.)

4.

Inyanga Lowlands. Typified by the van Niekerk ruins. Seventeenth century to eighteenth century A. D. (Chap. 3.)

Some of the Bantu peoples of the Inyanga area built rough stone walling long after the earlier people had left the area.

End of Page 7

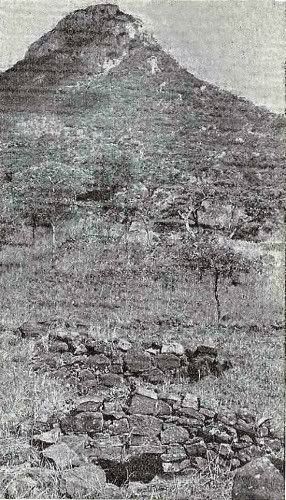

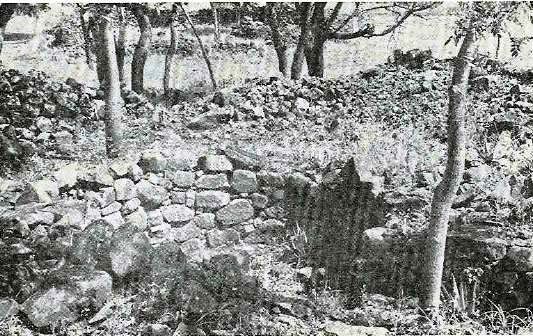

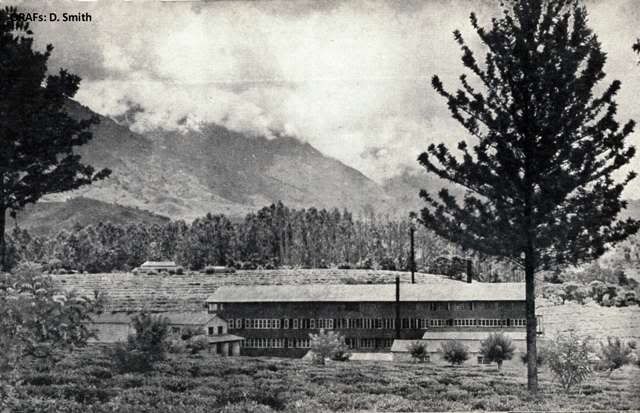

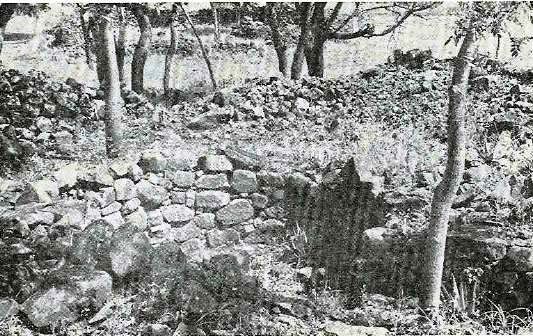

Plate 2

The First Ruins at Harleigh FarmEnd of Page 8CHAPTER 1Rock Paintings at Diana's Vow and Ruins on Harleigh FarmThese two sites are well worth visiting as they are unlike anything found in the Inyanga area proper and are able to give the visitor a quick glimpse of the two types of antiquities for which

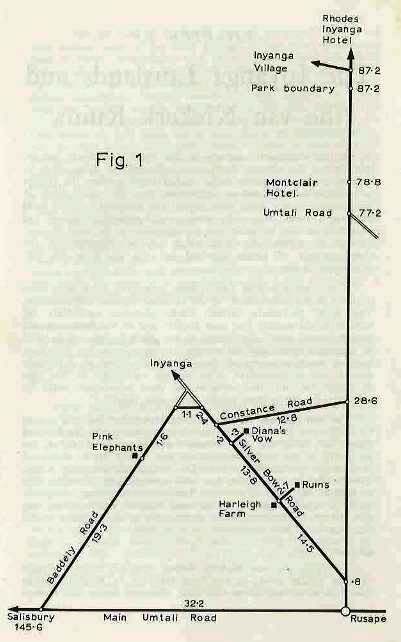

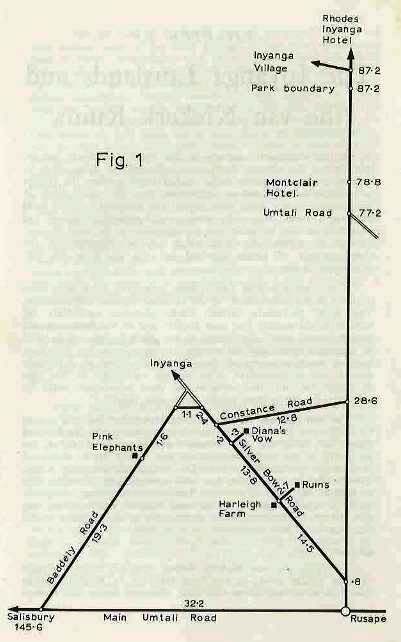

Rhodesia is most famous - the rock paintings and the many small ruins of similar style to Zimbabwe itself. The roads are good, though not tarred, and access to the sites themselves is easy and involves no climbing. The routes are shown on Fig. 1, p. 18

Visitors from

Salisbury intending to visit either of these sites are able to take a short alternative route to the main one, over good gravel roads. Leave the main Umtali Road 145 km from Salisbury and turn left along the Baddeley Road, following the signposts to Inyanga. After 19 km one reaches

"Pink Elephants". This is named after a rock painting, high above an overhanging shelter on the summit of the steep little kopje immediately west of the road. The path to the top is signposted. The paintings themselves arc simple, six elephants in a faded red pigment, not by any means great or unusual examples of the rock art but pleasing, full of life and very easily accessible. One and a half kilometres past this site, take the right hand fork to Rusape and after 3½ km the entrance to a much more important painting. Diana's Vow, is reached (see below). Harleigh Farm is a further 13¾ km along the same road.

For visitors starting at

Rusape, take the Inyanga road and turn left on the outskirts of town onto the Silver Bow Road; after 14½ km

Harleigh Farm is reached and the ruins are along a farm road 3 km to the north. A further 13} km along the Silver Bow Road brings one to D

iana's Vow Farm where a sign indicates a gate on the north of the road. Here a road leads down ½ km to the large rock under whose shelter the paintings arc to be found. Immediately past the paintings, Constance Road turns off north and provides a good return route to the main Inyanga

End of Page 9road, which it rejoins after 13 km, 29 km out of Rusape towards Inyanga.

The paintings at Diana's Vow (National Monument No. 64). are the only surviving fragment of a much larger scene, of which faint traces can still with difficulty be distinguished on the left of the rock. Nevertheless, the portion that remains is the most complex, clear and vivid example of the final splendid flowering of Rhodesian rock art. The main scene depicts two long friezes of human figures, emblazoned with white stripes, dots and head-dresses. Several are masked. Above them is laid out all the panoply of their equipment — baskets with handles, skins, bows, quivers, truncheons and a mass of edible fruits or roots. The whole scene is enclosed in a triple series of curved lines. Above this is a much larger reclining male figure, in similar style to the small ones below, also masked and clothed in an elaborate white dotted garment. Below him a simpler female figure echoes his posture. Dogs, a chicken, a snake and further humans adjoin the central scene. Underneath these figures can be seen isolated animal paintings in an earlier, simpler style — notably a buffalo. It is clear that all the human figures belong to a single scene. Such elaborate compositions only occur in the final phase of Rhodesian Rock Art. The white outlines and embellishments bear out that this is a late painting for white pigment is much more transient than the earth ochres that gave the reds, browns and yellows.

The interpretations of the scene have been many — notably that it represents the burial of a king — the large reclining figure — with his retinue presenting their funerary offerings*. It has also been suggested that it depicts newcomers of an Iron Age culture observed by the Stone Age artists and the apparently domestic dogs and chicken may confirm this. These interpretations may both be correct but neither is certain. Nevertheless, the event recorded remains unique and exciting.

Behind the boulder containing the painting the visitor will find a typical small w

alled kopje enclosure secluded among the boulders of a small plateau, with lintelled entrances, hut circles, platforms and daga floors. This is an example of a late ruin that nevertheless includes many of the features to be found at Inyanga itself. It is, of course, very much later in date than the paintings.

Harleigh Farm. (National Monument No. 72), contains two ruins of very different date and style. From where the visitor

*

This theory is discussed and the painting excellently illustrated in colour by the late Mrs. E. Goodall in Prehistoric Rock Art of Rhodesia and Nysaland, R. Summers ed.. National Publications Trait. Salisbury. 1959.End of Page 10

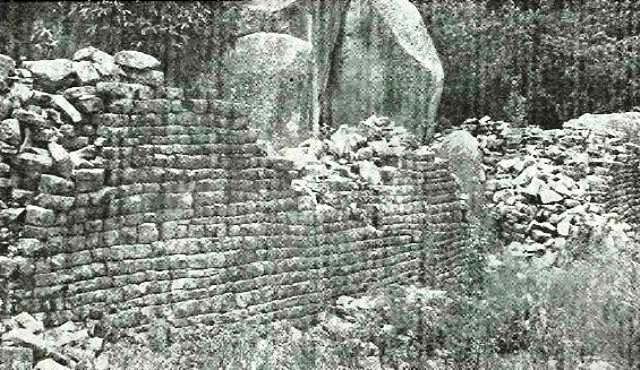

leaves his car, a path leads west through small wooded granite kopjes. After about 90 m the stone wall of the

First Ruin is visible on the north of the path (Plate 2). The granite blocks of the massive outer enclosure wall have been squared, trimmed and laid in straight, close fitting courses with a simple rounded entrance, all in a style very like the finest walling of Zimbabwe itself. Of the interior, little remains on the surface. When it was excavated in 1959 the pottery, finely made hut floors, benches and walls of daga that were revealed, confirmed that this is truly an outlying example of the late Zimbabwe ruin period, and so probably of the seventeenth century. Here also one of the very few skeletons of the period was recovered from a grave beneath a hut floor. After this building was deserted by the original builders, the area was later reoccupied briefly. The first European travellers, at the end of the nineteenth century, record that this ruin was held in great awe and a chief Chipadze was buried within it. Thatched pole mortuary huts were seen over his and three other graves. Their remnants are probably the stone circles to be seen today amongst the boulders beyond a second wall to the north east of the main wall.

Ninety metres further up the path just the

First Ruin a large boulder stands on a low outcrop of bare granite — on this will be found a few simple examples of

painted human figures.Returning to the car park, an isolated kopje with "balancing rocks" on its summit is visible beside a stream, across farmland 180 m to the north west. This is the site of the

Second Ruin. Two earth ditches surround the kopje, a very unusual feature. On the inner bank of the outer ditch the original wooden palisade has taken root to form the present line of trees. Within, the visitor will notice heaps of stone which would seem to be graves, but examination has shown that this is not the case — they are probably simply the result of clearing the land for building and cultivation. The central rocky outcrop is encircled by a wall with a lintelled entrance and on this kopje and the rocks adjoining it are many circular bases for both huts and grain stores while, under the highest rock, daga plastered walls enclose typical Shona graves.

This ruin has been described in detail by several travellers in the early 1890's including the famous explorer Selous*. They describe the palisade, ditches or "moat" and the ground within them heavily cultivated with tobacco and surrounded on the line of the ditch with a loopholed wall built of stone laid in mud mortar. It was known as "Chitekete and was the old kraal of Chipunza or Chipadze, chief of the Ungwe tribe who, under the same ruling dynasty (Makoni), still live in the area.

* F. C. Selous Travel and Adventure in South-East Africa. London. 1893. P. 340.End of Page 11

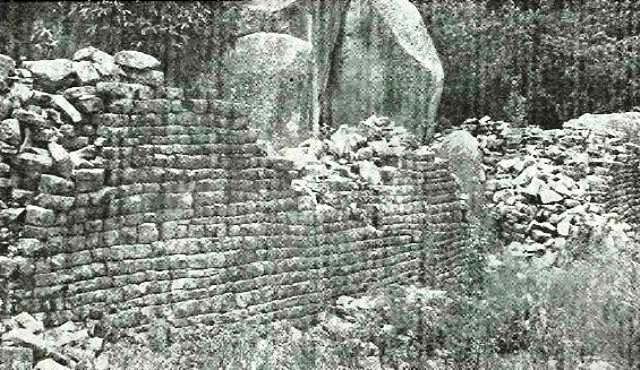

Plate 3 -

An upland Pit structure. Tunnel entrance,

platform and hut foundation are all visibleEnd of Page 12CHAPTER 2The Inyanga UplandsIn the sixteenth century, the climate of the high downs of Inyanga seems to have been generally somewhat drier than today, enabling grain crops to be cultivated. It was also a period of great tribal unrest. Probably as a result of these conditions people sought refuge in this comparatively inaccessible area. Many sites of this period are within easy reach of Troutbeck Inn and. more particularly, the Rhodes Inyanga Hotel.

Every visitor will have already heard of Inyanga's most famous feature named, from their first discovery, "Slave Pits". No evidence has ever been produced to support this popular name and so the less restrictive or dogmatic name "Pit Structures" is now used (Plate 3). Among many interpretations, the pits have also been considered fortified refuges for women and children in case of attack; grain stores; gold washing tanks; cattle, goat or sheep kraals; and. most recently and romantically of ail, as "symbolic representations of the Phoenician fertility goddess Astarte's womb". Let us examine all the features of a typical site to try to determine their true function.

The first thing that one notices is that they are almost always on sloping ground and are only partly, if at all. dug into the ground. Instead, they form the centre of an artificial platform, about 20 m across, which is retained by a stone wall on the lower slopes of the hill. On this platform will be found five or six stone circles of varying size linked by walls and forming the foundations of huts (daga floors, kerbs and low internal dividing walls still survive in the least disturbed examples). From the upper slope of the hill the pit itself is entered through a low tunnel, walled and roofed with flat stone slabs. The tunnels are curved so that the exit is never visible from the entrance. Halfway along, a gap in the roof now opens to the sky but this invariably originally opened into the centre of the door of the largest hut on the platform. This roof opening provided a method of closing the tunnel so that all access to the pit was controlled and protected by the occupants of the hut. The pits themselves arc beautifully made of close fitting stones laid without mortar. No traces of roofing have ever been found either round the tops of the pits or has fallen fragments, within them. They must always have been open. All this would seem to indicate that they could not have been intended for people to live in. Even should slaves have been housed in such cruelly exposed conditions.

End of Page 13the method of barring the tunnel would seem to be too insecure against a person intent on escape, for the tunnel is otherwise unguarded and undefended.

The floors of the pits were paved in stone, sloping down to a large stone lined drain, which ran under the platform and away. Frequently, large ditches lead from the drain to small earthwork dams or to the tunnel of a second pit, lower down the hill slope, and so through this pit and drain and away. This is evidence of a regular flow of water flushing the pits; and would seem to rule out any possibility of the pits being used for the storage of grain which would need, above all, protection from damp. The only reasonable explanation left is that the pit was used to house livestock. It has been suggested that dwarf cattlc were stalled in the pits but the only bones so far recovered from these structures give no support to this. It is more likely that the pit housed such animals as pigs, sheep or goats. In fact, Hall records that in the late nineteenth century, they were used precisely for this by Africans living in huts on the platforms. Pit structures, (singly, or more rarely, grouped in pairs in a single platform) occur alone or in groups of up to twelve or more. As one drives along the roads of this area, an isolated clump of trees or thick bushes can be taken as a strong indication that there is a pit beneath them. This is a country of intense grass fires and the pits provided good protection for saplings during the fire season.

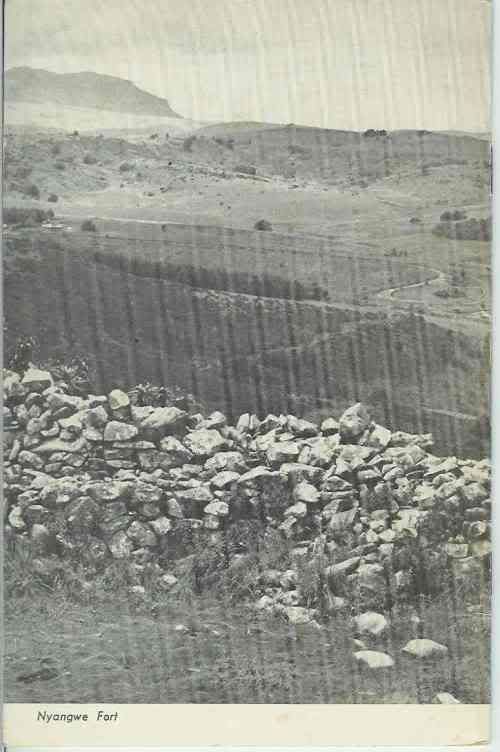

More dramatic, but much less common, are the

Forts. They are always in fine, commanding situations on hills and promontories, with wide views, and partially surrounded by steep rocky slopes. Their main features are the thick, high walls of large, close fitting, blocks of stone with low lintelled entrances, similar in size and construction to the pit tunnels. Frequently the walls are pierced at varying heights by small, square loopholes. These

loopholes seem strangely purposeless and even useless to modern eyes for they are not splayed and so give such a restricted view or field of fire that no weapon could be discharged effectively through them. The walls are often thickened to provide a raised walk inside, below the parapet. Usually there are low stone hut circles within the Forts.

The most convincing evidence of the engineering skill of the Upland builders are the

water furrows, simple earth ditches leading from perennial streams in a gradual gradient to the living sites. Often they run for several kilometres. Many have been destroyed and others adapted for use today, still feeding such places as the Rhodes Inyanga Hotel and several private houses and swimming pools. A little simple, shallow

terracing, built up only of earth, is sometimes found (for example, on the hillside behind Inyanga Township).

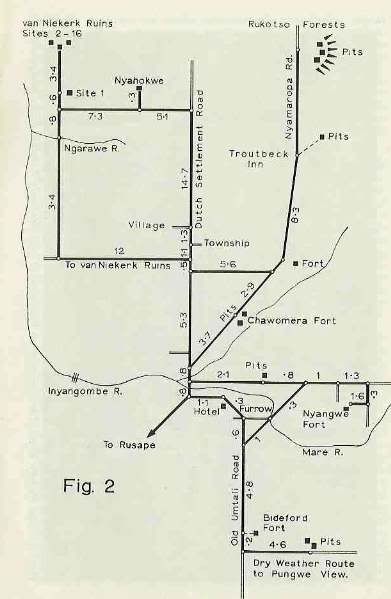

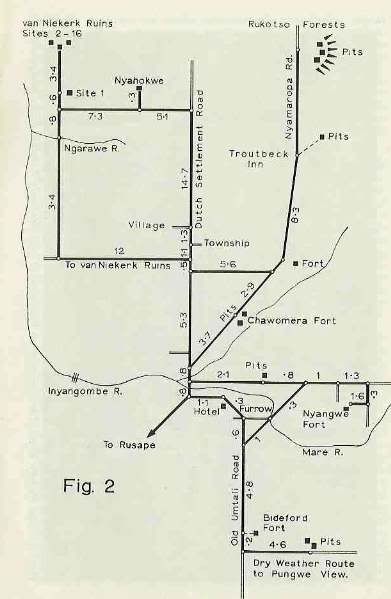

End of Page 14GUIDE (sec Fig. 2, p. 19).Rhodes Inyanga Estate (National Monument No. 10).The most easily accessible

Pit Structure near the

Rhodes Inyanga Hotel is reached by turning right from the Inyanga Village road (¾ km beyond the junction where the road to the Hotel meets the main Rusape — Umtali road). This Pit Structure, probably the one most closely examined by Maclver in 1905, has suffered greatly from constant visitors and the platform structures arc now scarcely visible. This also applies to a second pit in the trees a few yards north cast of this one.

If, from the Hotel, one takes the

Old Umtali Road, 275 m from the Hotel one crosses a large water furrow. This is still in use and can be followed along a picturesque footpath to its junction with the Mare river. Continuing along this road, 6 km from the Hotel, turn left along the

"Dry Weather Route to Pungwe View". Just under 5 km along this road there is a sign posted

Pit Structure immediately east of the road. It is intact and the massive stone foundation walls of three huts remain on the platform. Two-hundred and seventy five kilometres north east of it, across a small stream and valley, a clump of trees marks a pit where some of the very few remaining moulded daga walls divide two of the huts on the platform.

Returning by the same route to the Hotel, 3 km from the Pit one notices a small stone building, visible above the trees on the crest of a bare granite kopje. This is

Bideford Fort (MacIver's Southern Fort) and to visit it one must leave the car at the small stream, crossed immediately after rejoining the Old Umtali Road, and follow the stream in a steep climb up to the fort, now invisible from the road. This bleak, windswept little building, a single circular enclosure, is the simplest of the forts and seldom visited. It has all the features of a typical fort, in particular numerous loopholes.

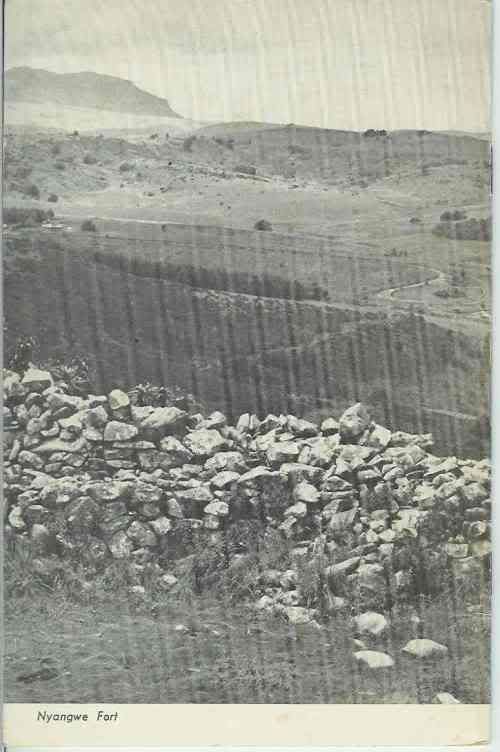

Nyangwe Fort, (MacIver's Eastern Fort), 5 km east of the

Rhodes Inyanga Hotel (see cover), is the most complex fort, crowning a rocky promontory with a steep drop to the streams below the northern and southern sides. The summit is crowned by the original enclosure, which is surrounded by five further enclosures. All of these have loopholes and most contain low stone circles of hut bases. The quarry from which the stone for the walls was probably obtained is the very overgrown pit on the east side of the fort. From a small enclosure 275 m west of the fort, Summers re- covered the only skeleton of the Upland Culture known. It is typically African and is discussed in detail by Professor Philip Tobias in the monograph Inyanga.

End of Page 15On the road to Troutbeck and the Inyanga Downs, 4 km after turning right off the main Inyanga Village road,

Chawomera Fort is visible immediately east of the road. (Maclver's North Eastern Fort, Summers' Site XXXV.) The single enclosure of the Fort has all the typical features seen before and so needs no further description. Notice, however, a few grooves, in which grain was ground, on the bare granite of the path leading from car park to fort. More important, strung along both sides of the road below the fort, there are at least twelve

pit structures which, with the fort, formed a complete village. Clumps of trees mark the positions of these pits. Particularly good examples are the pair just below the car park of the fort and the southern example of a further pair, 180 m further north along the road towards Troutbeck and just cast of it. Between each pair of pits one will notice earthern hollows or depressions, from which the earth fill of the pit platforms was dug. Continuing to Troutbeck or the Inyanga Downs, ¾ km after passing the road that leads down to Inyanga Village, a further Fort will be noticed. ½ km cast of the road. It is in the most dramatic position of all, with precipitous slopes on three sides, and connected only by a narrow ridge to the hills beside the road. It is however, scarcely worth visiting for it is very overgrown with aloes and access to it is difficult.

Inyanga Downs.From Troutbeck Inn, a well-known signposted path leads about 2½ km east through private lands to two typical

pit structures but these have been disturbed and the platform structures are no longer clear.

Much more worthwhile is the journey north along the Nyamaropa Road for 5 km from Troutbeck Inn. Here, just before entering Rukotso Forests, about ¾ km east of the road and lower than it, a level, uncultivated plateau will be visible, falling away in steep slopes on its eastern and southern sides to the Tsanga river valley below. In the clumps of trees on the edge of the plateau and fringing the cliffs, a great number of

pit structures occur in unspoilt surroundings*. Here will be found features not seen before. One platform contains two separate pits, each with its own tunnel. Most notable arc the large furrows linking the drain of one pit to the tunnel of a pit below and then leading to what seem to be earth dams, (though some of these are certainly pits robbed of their stonework). Notice how the tunnels often start from excavated hollows.

* Called Site D by Mrs. Enid Finch who described the area in a paper in Vol. XLII of the Proceeding of the Rhodesia Scientific Association. 1949End of Page 16CHAPTER 3The Inyanga Lowlands and the van Niekerk RuinsIn the seventeenth century, as the Inyanga Uplands became infertile and the climate deteriorated sufficiently to cause crops to fail, people moved westwards to the hill country below the Downs and established the Lowland settlements. Here the rocky slopes of almost every hill or kopje were cleared and encircled by stone built

terraces. It seems that every stone over hundreds of square km has been moved by man and incorporated in his vast designs. Though the quality of workmanship may be unexceptional, the sheer quantity of labour involved has put all. from the first discoverers, in awe.

It is often presumed that a huge population must have been involved in the construction of the Lowland terraces and buildings. This is by no means certain. Under primitive agriculture the terraces would quickly lose their fertility and so the farmers would have to move, after a few years, to new ground. This would again be cleared of stone and the terraces and enclosures may well have been as much a means of disposing of the stone as a strongly desired end in

themselves. With shifting agriculture in this type of terrain for. say. two centuries, no great population would be necessary for the striking results to be seen today.

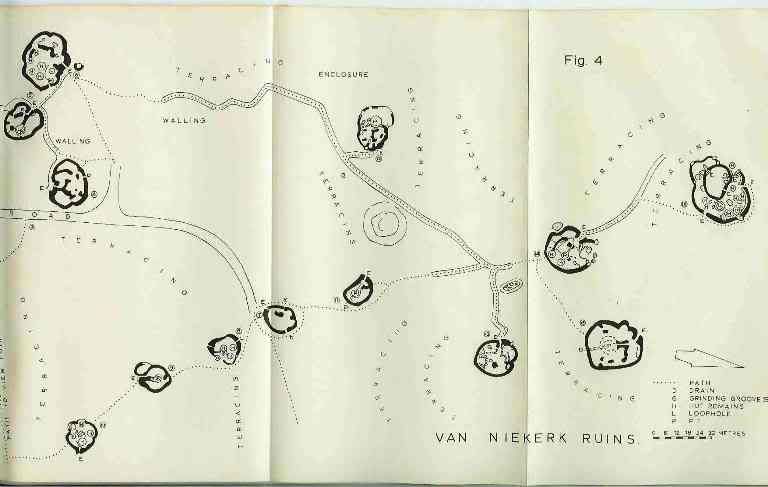

The

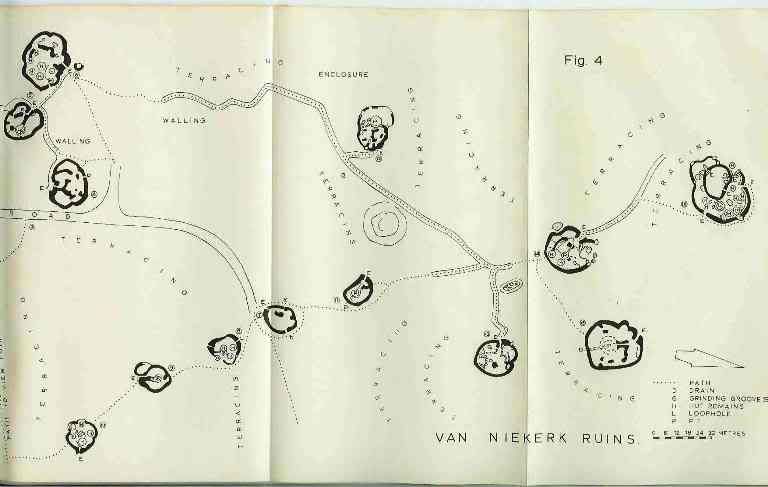

van Niekerk Ruins (National Monument No. 53), named by Maclver in 1905 after the early Inyanga settler who guided him round the ruins, are only a small portion of land 40 sq km in extent, in the ccntre of the ruin area, ceded to the Historical Monuments Commission in 1946. Even within this area only a tiny, though representative portion has been opened up to the visitor. The magnitude and scale of the total Lowland culture must always be borne in mind as one views the small fraction visible at any one time. Much is still unexplored and months could be spent in the examination of new areas.

GUIDE.To reach the

van Niekerk Ruins, turn left from the main Inyanga Village road. 7

¾ km from the fork to Rhodes Inyanga Hotel. A short way along this road, the view across the western

End of Page 17 End of Page 18

End of Page 18 End of Page 19

End of Page 19

Plate 4

van Niekerk Ruins. The typical pit of Enclosure II with Enclosure 7 visible in the

back ground.

End of Page 20lowlands opens out and to the north west the great conical, granite mountain,

Ziwa, will be seen, reaching 400 m above the plain. Just west of it and equally prominent, though 220 m lower,

Hamba rises; while stretching east the range rises to the further flat topped summit of

Nyahokwe, only 45 m lower than Ziwa itself. It is at the foot of these hills that the terraces and ruins lie. Following the signposted road, after a further 15{ km one crosses the Nyarewe river and enters the ruin field. 1± km further again (ignoring the turnoff to Ziwa and Nyahokwe) one reaches the first site. Posts will be seen marking and numbering the sites, and this numbering is followed in this guide.

Site 1 is an isolated granite kopje on the east of the road (Summers' Site III) and the walls defending it are clearly visible. The path leads up to a loop holed wall with low, lintelled

entrance. Here the horizontal slots for both a draw bar and a further bar to lock it in position can be seen. The entrance is protected by a small enclosure or

bastion immediately opposite, again entered through a lintelled doorway. Turning left and through vet a further lintelled entrance, one reaches the living area, a scries of asccnding platforms with the decomposed daga fragments of former huts upon them. From the top. looking south west, a stone walled lane can be seen leading to the rear entrance of the site,

cairns of piled stone adjoin it — probably only the result of clearing the land for cultivation.

One is now in the ruin area proper and the slopes of the kopjes all along the west of the road are

terraced from top to bottom, with retaining walls of untrimmed dolerite blocks following the contours. The terraces arc usually 2 —3 m apart and 1 m high. The soil they were intended to retain has largely disappeared through erosion leaving the walls free standing.

The road skirts the foot of Hamba and 3{ km beyond the fort

Enclosure 2 is found on the left of the road. This is a very well preserved, typical example of the simplest basic type of Lowland living site. Close fitting dolerite blocks face both sides of the circular

enclosure wall, and the space between is filled with dolerite chips and gravel. A typical lintelled entrance with draw bar led to a tiny enclosure, almost an

entrance hall, from which a

tunnel of exactly the same size as those in the Upland pit structures led down to a central

circular pit. This is much smaller and shallower than those of the Uplands but has the usual drain opposite the entrance, coming out at the base of the outer enclosure wall. The level of the ground within the enclosure is artificially raised well above that outside. It is immediately apparent that this typical Lowland enclosure has much in common with the Uplands pits. The great

End of Page 21difference is that the Lowland enclosures are built on level ground and make use of the very abundant stone. As a result, a free standing outer wall replaces the Upland platform, and protects the living area. The central pit, though small, must also have been used for keeping such livestock as sheep or goats. Of course, as the tunnel is above ground level, no hut could be built on it, so the sunken entrance hall and the doorway (with slots for a wooden draw bar) replace the security devices of an Upland Pit.

Such enclosures — homes of the people who worked the terraced lands — are scattered amongst the terraces, sometimes concentrated in certain areas and within easy reach of each other, but never forming true villages. Enclosure 4 marks the start of such a concentration of at least 15 enclosures. This area is right in the middle of the ruin field and since MacIver described it in 1905 (Area N.II) has been very frequently visited. A sad result is that little of the fragile daga structures of the interiors will be found.

Ignoring

Site 3 for the moment, the visitor may park his car near

Enclosure 4 and using the plan (Fig. 4) choose the extent of his tour. The enclosures numbered 4—16 have much in common with the typical enclosure already described. It is therefore not essential to visit all.

Enclosure 4 has no pit. The interior contains several lengths of wall and fragments of buttressing. These probably originally ran between hut walls and so formed separate divisions, one of which doubtless housed livestock and replaced the pit. The outer wall is greatly thickened at the entrance, and a tortuous approach results — a feature very common where there is no "entrance hall". Just within the entrance a low stone bench makes the approach even narrower. The walls pass over many large natural boulders and so incorporate them in the fabric.

Enclosure 5 has many interior walls, one of which bisects the original pit. Outside the entrance, a large upright stone or monolith was set up, probably as a marker. Such stone markers are a feature of both the Upland and Lowland buildings. The stone lined paths such as those connecting Enclosures 4, 5 and 6 will be described later.

Enclosure 6 is the largest enclosure and most worth visiting. Here the circles of at least seven huts can be traced and their method of construction clearly seen. Flat slabs were set on end in the ground and further slabs laid across them to form a horizontal platform clear of the ground. This was then thickly plastered with

End of Page 22daga to form the hut floor. The collapsed remains of several such floors can be seen. Grain stores today are constructed in a similar way and the smaller circles in this enclosure probably served a similar purpose. In the interior many natural flat rock surfaces bear

grooves caused by grinding grain, while several

quern stones lie loose in the enclosures. Grain must have formed the principal crop and diet. The inner dividing wall has a

semicircular recess with a raised floor, barred by two upright stones. These may have been the backrests of seats under a roofed

shelter or verandah. It again divides and destroys an early pit. Examination of the outer enclosure wall shows that it was not a single continuous circle but built as a series of separate adjoining arcs, often adapted to the curve of a hut. The huts were therefore sometimes built before the wall. These enclosures are not therefore primarily defensive but simply protective shelters from the penetrating winds and rain of the Inyanga winter. There is a single

loophole in the outer wall.

Enclosure 7 is very simple. The collapse of the two entrances reveals the draw bar slots particularly well.

Enclosure 8 has important historical associations, for it was probably here that MacIver in 1905, saw the many remains of hut daga and daga floors, and for the first time realised the strong relationship between the ruin builders and present Bantu techniques. As a result, for the first time he advocated an indigenous origin for all the Rhodesian ruins.

Enclosure 9 is a very simple one with pit and collapsed tunnel.

In

Enclosure 10 there is a large circle, built directly on the ground and clearly divided down the centre, with only the raised eastern half having a daga floor. This type of building is a

characteristic feature of the ruins and Summers has suggested that they were grinding and winnowing places, and, though the daga floor was protected by a low wall, that they were not roofed.

Retracing this path, one passes

Enclosure 11, very simple and typical, and continues up towards

Enclosures 13 and 14.

One is now clearly following the original stone lined trackways or lanes that are an outstanding feature of the Lowland Ruins. These narrow paths run for long distances through terracing, and connect the enclosures with open land. Here one soon reaches a main junction, from which one can go north to enclosure 14, east to 13, south to 12 or south east for several hundred metres past 12 to our starting point near 6, all following the original lane, still intact. Their purpose was mainly to protect the crops growing on the

End of Page 23terraces from the livestock as they were driven from grazing to shelter within the enclosures. A recent startling romantic explanation is that they were training tracks for domesticating the local African elephant by Phoenicians, apparently putting Hannibal's experiences in the Alps to local advantage. It seems however, that the admittedly more mundane reason given meets the problem rather better.

Enclosure 13 is interesting for the raised and sheltered grinding place on the right of the entrance and for the large circular cairn constructed in the centre. Such cairns have not been satisfactorily explained. In an enclosure such as this (without a pit) they were probably intended as granary bases out of reach of livestock.

Enclosure 14 adds nothing further, though it is large and elaborate and has terraced platforms for the huts.

Enclosure 15 adds little further. Its central pit appears again to have been abandoned and to have been purposely filled with stones.

Finally, one climbs to

Enclosure 16. This massive structure, much larger than any other enclosure, was most probably a Fort. It commands magnificent views over the ruins, particularly west towards the long mountain of Jowani, whose southern end is terraced from top to bottom. North west and northwards further terracing is clearly seen. Here we get some idea of the magnitude of the ruins. The

Fort has a massive external wall, stretching across large boulders, complete with parapet walk, but none of the loop-holes of the Upland forts. The interior has traces of several large huts, not all on stone bases. Within is a second complete stone enclosure; its main entrance, protected by a drawbar and horizontal lock is in a portion of wall added to the inside of the original wall to form a raised walk over the entrance.

One now returns past Enclosure 14 and then follows the long trackway to

Enclosure 12. This is of little interest save for the unusually large pit, again partially blockcd in its own separate lower enclosure. The main entrance to the enclosure has also been blocked. Continuing on the same trackway one reaches Enclosure 6 and the starting point.

It only remains to draw the visitors attention to

Site 3 from whence one can follow an original terrace towards the east and so see how well the terracing follows the contours. One then reaches a

viewpoint from which one sees something of the terraces stretching eastwards towards

Ziwa mountain.

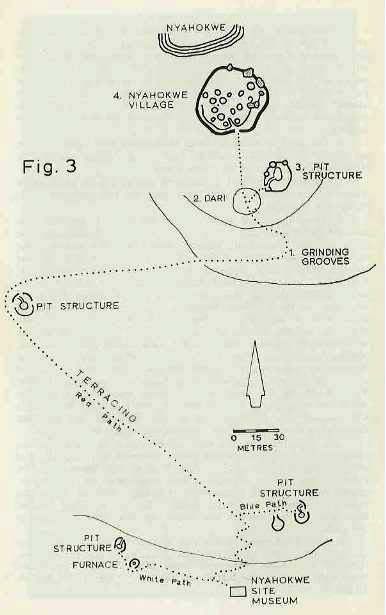

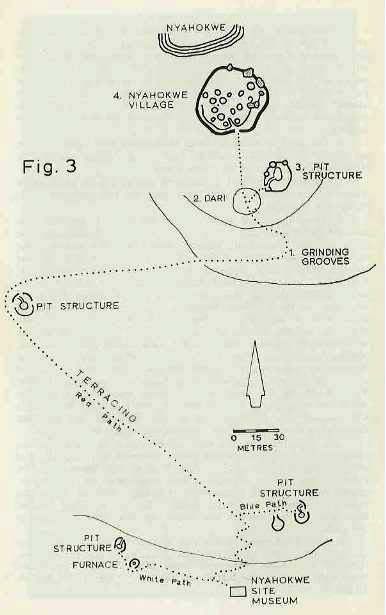

End of Page 24CHAPTER 4Ziwa, Nyahokwe Village and Site MuseumJust before entering the van Niekerk Ruins, a signposted road forks right to

Nyahokwe Site Museum. This is reached 8 km from the fork, the road passing through the Ziwa farm.

On this farm arc several sites of the

Ziwa people, the earliest Iron Age inhabitants of Mashonaland. In 1905 MacIver had found large quantities of their pottery at a place he consequently named the "Place of Offerings". (This is actually within the van Niekerk Ruins, about ¾ km north of the saddle between Ziwa and Hamba.) He did not however realise the full significance of his finds. Although the culture lasted for at least 700 years from 300 A.D., visible remains are very few for the people lived in flimsy huts on small secluded plateaux in the hills, and only rarely did they build rudimentary terraces in stone. Analysis of the bones from Ziwa graves shows the people to have been predominantly Negroid. Though these sites cannot be visited, examples of the Ziwa pottery and ironwork are exhibited in the Site Museum.

From the

Site Museum paths lead to several points of interest. The

white painted poles lead a few yards west to the reconstruction of an

iron smelting furnace. The low, circular stone enclosure wall, the size, daga fabric and supporting arms or buttresses of the furnace are typical of "Iron Age" and later Shona furnaces. The rectangular shape and particularly the small human figurine arc more unusual, though many Shona furnaces have human breasts and scarification modelled on them. Behind the furnace is a simple pit structure with an unusually small pit.

The red and blue poles lead the way up to Nyahokwe mountain. After a short distance the

blue poles diverge east to a further simple

enclosure and typical

pit structure. The red poles lead on a steep climb of about i km past terracing and a further pit structure to the

Nyahokwe Village site (National Monument No. 99), crouched under the cliff face of the very summit of the mountain. This is a complex settlement, not at all usual in the Lowlands, with several elements most commonly found in the Uplands. It may have formed the quarters of a ruling group or chief. Granite replaces the dolerite used in the van Niekerk Ruins. There are four separate elements.

End of Page 25 Nyahowke Village, below Nyahokwe Mountain. The "dari" is seen in the foreground.End of Page 26

Nyahowke Village, below Nyahokwe Mountain. The "dari" is seen in the foreground.End of Page 261. Just east of the path as it approaches the village, and about 100 m below it, the level plateau of bare granite is scarred by a great number of

grinding grooves, often six or more purposely grouped within reach of one person seated at their centre. It has been suggested that these were probably used in the preparation of ores for smelting rather than for grinding grain. The visitor will have already noticed the great number of loose querns in the area, which one would certainly think would have proved ample for any grain grinding.

2. The great level circle, 18 m in diameter, with upright stones set round its perimeter formed, from local African parallels, a "

dari" or meeting place of the village elders.

3. Leading off the

dari to the north east is a large pit structure whose typical features of tunnel, pit, platform and particularly hut circles are very clear.

4. The V

illage site itself is enclosed by a rough wall and entered through the usual lintelled entrance, which gives onto an inner passage. The sloping ground within contains numerous stone

slab foundations of what were probably grain stores and also one strange circular

cairn, almost a small "conical tower", whose real function is unknown. On the inner face of the outer wall are several small square niches or "cupboards" — a feature occasionally found elsewhere in the Lowland buildings. Evidence from the base of excavations of the village showed that the Ziwa culture preceded the stone building on this site and that from the eleventh century an apparently gradual and peaceful

Transitional phase occurred, marked by elements of both the Ziwa and Lowland cultures, from the eleventh to perhaps the fifteenth centuries, when the builders in stone took complete possession. The village was excavated by

Mr. F. O. Bernhard, the owner of Ziwa farm, who gave the land on which the village and museum stand to the Historical Monuments Commission. On returning, notice the

terracing of the hills immediately to the west of the museum and village site.

The

Site Museum provides exhibits, and a comprehensive summary, of the many cultural phases described in this guide. The exhibits, all of local origin, range through the Stone Age, the Ziwa culture, the two Inyanga cultures themselves, up to late nineteenth century Shona, particularly Unyama, material. Here are pottery, weapons, metal work, beads: the sparse relics of the households, whose remains and whose life have been glimpsed in this guide.

Instead of returning via the van Niekerk Ruins, the visitor may use a slightly shorter route and continue eastwards past the museum, reaching the

Dutch Settlement Road after 5i km, where one turns right to reach the turnoff to Inyanga Village after a further 15 km.

End of Page 27 Fig 3End of Page 28CHAPTER 5Cecil Rhodes and Inyanga

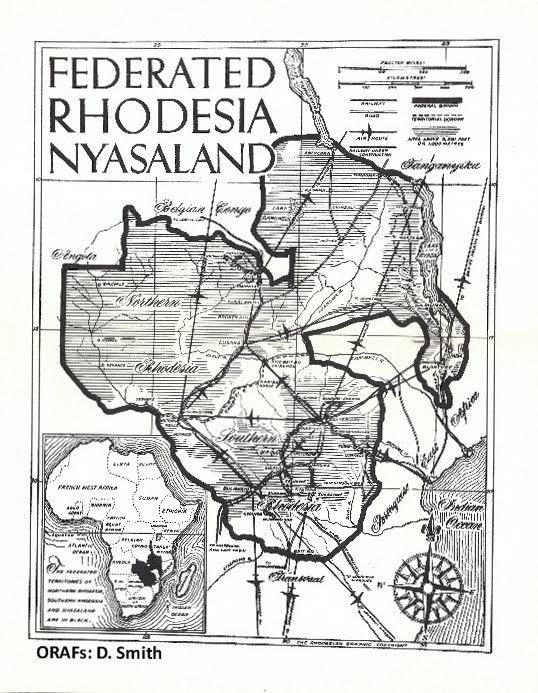

Fig 3End of Page 28CHAPTER 5Cecil Rhodes and InyangaCecil Rhodes, who first developed the Inyanga National Park, on which so many of the antiquities lie, found at Inyanga, as he did in the Matopos Hills, a place exactly in tune with his character. Here again the wide landscapes and rugged country exemplified, for him, his own Rhodesia and echoed his broad vision. Three times, at critical points in his career, he turned to Inyanga for rest and inspiration.

Early in 1896, after the debacle of the Jameson Raid, Rhodes had resigned as Premier of Cape Colony and came to Rhodesia, then in the throes of rebellion. At the end of October, he had personally and almost alone brought the Peace Indabas of the Matopos to a triumphant conclusion. He now had to face a Select Committee of the House of Commons enquiring into the Jameson Raid. On his way from Salisbury to Beira and then to England he was persuaded to visit Inyanga for the first time. Its attraction was immediate and his reaction characteristic. "Dear McDonald, — Inyanga is much finer than you described. I find a good many farms are becoming occupied. Before it is all gone, buy me quickly up to 100,000 acres and be sure you take in the Pungwe Falls. I would like to try sheep and apple growing. Do not say you are buying for me. Yrs. C. J. Rhodes." Thus he wrote to his Rhodesian agent while on his way to England.

At the end of 1897 Rhodes, the Enquiry over and his health failing, was on his way back from Rhodesia to re-enter politics and fight the Cape elections. Again he made for his new Inyanga estates. On the way from Salisbury, he was attacked by malaria. With a weakened heart, for several weeks he lay ill at his Inyanga

End of Page 29homestead with Jameson at his side, both as doctor and friend. As he recovered, they spent long periods in the veld riding, exploring shooting and initiating the experimental farming which the Estate still continues.

For a last time, after the relief of Kimberley where he had been besieged, Rhodes returned to the Eastern districts, and particularly Inyanga, during July and August of 1900, again riding and camping in the veld he loved.

On his death, eighteen months later, he left his Inyanga Estate to the people of Rhodesia to be used for the "help and instruction of the settlers". This Estate was proclaimed a National Monument and is now the centre of the Inyanga National Park. The homestead and stables built by Rhodes form the core of the present Rhodes Inyanga Hotel and still contain furniture and photographs of the period.

Characteristically, Rhodes actively encouraged and assisted the settlement of many Boer families at Inyanga, a fact commemorated in the name of the "Dutch Settlement Road". One such settler was Major P. H. van Niekerk, who had distinguished himself in both the Africander Corps in the Matabele Rebellion and in the Boer War. He was a friend of Rhodes and settled on Bideford Farm about 1903. His archaeological interests and assistance to MacIver are commemorated in the name van Niekerk Ruins.

AloeEnd of Page 30Man and Plant at Inyanga

AloeEnd of Page 30Man and Plant at InyangaBy

G.L. Guy B.Sc.

Visitors to the Ruins, particularly the Lowland area, often ask

"Why not date the ruins by tree rings?" "Haven't they done something like that in America.The truth is that it has been tried but the great majority of indigenous trees, either show no marked annual rings or put on false rings due to drought, or unseasonal rains, or defoliation caused by fire or insect attack. Ring counts of Mlanje cedar offered the greatest hopes, but present techniques are incapable of dealing with such resinous woods. Recent experiments with baobab are proving interesting, though, and this species may well prove to be the oldest living thing.

The Uplands of Inyanga are a sad reflection of what happens when man is unrestrained in his use of natural resources. It is probable that the vast grassy areas were clothed in the same type of forest that now clings in isolated patches to the eastern slopes of Mt. Inyangani, slopes too steep or inaccessible to make the exploitation of their timber worthwhile, even with modern methods. One of the world's finest timbers Mlanje cedar (Widdringtonia whytel) which must have been common in the original forests, is now found only as fire scarred stunted small trees in rocky places or along streams, while Rhodesia's other beautiful conifer, Yellowwood (Podocarpus rnilanjianus) is found only in the depths of the surrounding forest.

The forests have vanished mainly through fire, which must have been used to clear land for cultivation, to provide fuel for household purposes and for iron smelting. Once the forest was

replaced by grass, fires lit to provide fresh grass for domestic animals, to drive out game and other animals, and to make wide open short grass areas to prevent surprise attacks from invaders, the fires nibbled annually at the forest verge and each year the forest shrank a few feet, and the housewife had a few more yards to travel for her fuel.

Today, a few surviving tree ferns are found in the deeper stream beds, a few of the more fire-resistant trees such as Waxberry (Myrica pilulifera), white elder (Nuxia florlbunda), cabbage tree (Cussonia spicata) and Mlanje cedar survive on rocky outcrops where fires barely reach them, and the great forests have vanished. But those who have the time will be well repaid by visits to the surviving

End of Page 31

Plate 6

Terracing in the Inyanga lowlandsEnd of Page 32forests where such beautiful flowering trees as the Cape Chestnut (Calodendrum capense), Kannabast tree (Dais cotinifolla), Forest fever tree (Anthocleista grandiflora) with its giant leaves and sweet scented flowers, the brilliant Kaffirboom (Erythrina lysistemonl the shiny leaved Wild holly (Hex mitis), the tube flowered Notsung (Halleria lucida) arc to be found, together with a great wealth of annual flowers including a giant Haemanthus and a great variety of arboreal orchids. Among the trees without conspicuous flowers are the yellowwood Cape beech (Rapanea melanophloeos). Assegai wood (Curtisia dentata), with brown hairy twigs and opposite leaves, wild peach with crushed leaves smelling of almonds (Kiggelaria africana), wild lemon wood (Xymalos monospora), Croton sylvaticus and Macaranga mellfera.

The western slopes of the mountains carry "forests" of miniature Msasa (Brachystegia spiciformis), perfect in shape but only a few feet high, and nearly every rock outcrop carries clumps of the wild medlar (Vangueria infausta).

But the flowers of the Uplands are wonderful; flame lilies arc common, but are often more yellow than red, there are all sizes of Aloe, particularly in the ruins, and the red fire lily, which springs up on burnt ground is outstanding. Gladioli are worth looking for and so are the varieties of ground orchids, there are several heathers and the "everlastings" are also prominent. Wet places have sundew and other lovely flowers; as high as the summit of Inyangani are Chirona palustris and several of the Dissotis family. There are too many flowers to be listed here and visitors are advised to enjoy themselves by counting the number of species they can find. Those fortunate enough to come on the shy Streptocarpus cyanandrus will agree it has few equals.

In comparison with the indigenous forests, the man-made forests of wattle, pine and eucalyptus are dull indeed, but they do save the natural beauty from further spoliation.

The Lowland sites by contrast are well wooded with tree species much more resistant to fire and capable of springing up from the roots after being burnt or cut.

The dwellers in these parts were great fruit caters, if one can judge by the variety of edible fruit trees and shrubs found within the ruins. Not all arc palatable to those accustomed to cultivated apples, pears, peaches, plums, etc., but they are edible and many must have been brought in by parties of women and girls, to grow from discarded seeds. The few baobabs on the hills must have been brought in by human agency and the presence of the recently discovered juniper (Juniperus procera), is bound to cause argument:

End of Page 33it has previously been known only 1000 km to the north. But interested visitors should look for the more than 30 wild fruits to be found and in an area still to be properly covered botanically, some clues of the origins of the peoples may be found. Common fruits are muhash (Parinari curatcllifolia) mzhanzhc and mahobohobo (Uapaca kirkiana) numnum (Carissa edulis) — (Flacourtia indica) several wild figs and further north, the delicious marula (Sclcrocarya caffra).

The aloes of the lowland ruins arc particularly beautiful, the brilliant flowers set off by the dull rock walls, but in their season the equally beautiful but smaller Babiana hypogea, Bells of St. Mary richodesma physaloides), Rhodesian bluebell Lapeyrousia rhodesuina) some of the ground orchids (Eulophia spp) mostly the brilliant pimpernel (Worniskioldia longepedunculata), and a long list of others, are well worth looking for; even the parasitic witchwood (Striffa asiatica) has its beauties.

Further ReadingCarl Peter's The Eldorado of the Ancients (London 1902). contains the first full description of the exploration and antiquities of the Inyanga area. It is, besides, a very illuminating and entertaining example of the Victorian approach to travel in the interior and to the romantic origins and purpose of the ruins.

Dr. Randall MacIver's Medieval Rhodesia (London 1906) is the earliest description of the ruins to make real use of archaeological techniques. His descriptions, plans and photographs arc very detailed particularly for the van Niekerk Ruins while many of his conclusions have stood the test of time. It also studies Zimbabwe and many other well-known Rhodesian ruins.

Roger Summers' Inyanga, Prehistoric Settlements in Southern Rhodesia (Cambridge 1958) should be consulted by anyone wishing to understand the prehistory of this area. Not only does it give detailed accounts of a large number of excavations, with man} plans and diagrams, and the dating evidence gathered from them, but the pottery, beads, skeletal remains, botany and Stone Age remains are all separately analysed in detail by different specialists. Finally, a general picture of the place Inyanga holds in the pre-history of Rhodesia and further afield is reconstructed.

Since its publication, F. O. Bernhard has given an account of the earlier Iron Age period in a paper "Notes on the Pre Ruin Ziwa culture of Inyanga" in Rhodesiana (The Rhodesiana Society. P.O. Box 8628. Causeway. Salisbury. 1964).

End of Page 34 End of Page 35

End of Page 35 Back CoverEnd of Article

Back CoverEnd of ArticleThanks to P.S. Garlake and the Commission for the Preservation of Natural and Histrorical Monuments and Relics, and to the printers.

Thanks to Diarmid Smith for making a copy of this document available to me and thanks to Robb Ellis for his assistance.

Eddy Norris

Napier

May 20, 2010

This prototype of a Rhodesian car, with design and over-all concept at 80 per cent, local, is going through its final trials. The manufactured cost is 55 per cent. Rhodesian and the local weight content is 41 per cent.

This prototype of a Rhodesian car, with design and over-all concept at 80 per cent, local, is going through its final trials. The manufactured cost is 55 per cent. Rhodesian and the local weight content is 41 per cent.