Inyanga with special reference to Rhodes Inyanga Estate

INYANGA

by

R. W. Petheram on behalf of The National Trust of Rhodesia

1974

Foreward

It is with a deep sense of gratitude that the National Trust of Rhodesia acknowledges the work of Mr. R. W. Petheram in his preparation of this brochure. He spent many hours in research, made contacts with many people who had personal knowledge and experience of the early developments of Inyanga, and was tireless in his efforts to present as factual a history as possible, written in a style which would grip the imagination and the Interests of his readers.

This is the first publication of the National Trust the first of many it is hoped and it is fitting that it should be dedicated to the name of Mr. R. W. Petheram, to whose devotion and inspiration it belongs.

The National Trust are proud to present it to the public and trust It will be a source of pleasure and of great interest to all who will be privileged to share its contents.

Sir A. D. Evans, K.B.E., B.A., LL.B., President, The National Trust of Rhodesia.

Introduction

The Administrative District

The Native Commissioner's office was moved several times before it came to rest at its present site and the name followed it and was eventually applied to the whole district.'

The farm Sanyanga's Garden, mentioned in Mr. Reid's note, is within a few kilometres south-west of the Pungwe Falls. The association of this farm with the first Native Department camp is also recorded by R. Summer [2]

Inhabitants of the past.

There is evidence of very considerable settlement in days gone by, some of it of great antiquity.

Crude tools associated with the early Stone Age of some 40 000 to 50 000 years ago have been found [3] but the probes of the historian and the archaeologist have much to uncover in relation to the intervening centuries.

Some evidence of late Stone Age occupation is provided by "Bushman Paintings" not, perhaps, as numerous as in certain other parts of Rhodesia (there are large tracts without the caves and rock over-hangs favoured by those "artists") but none the less significant. C. B. Payne [4] has drawn attention to extensive paintings on the hill Nyapani in Bannockburn North, and isolated paintings in shelters near Sanyatwe and Inyanga Village.

R. E. Reid, to whom reference has already been made in connection with the origin of the name "Inyanga", has supplied the writer with a most interesting note on a cave, difficult of access, called "Jinjimavara" in the vicinity of Mt. Nani in the Inyanga North Tribal Trust Land. On its walls appear signs and symbols with possibly "magical" connotations, and numerous animal drawings including tsessebe, pig, rhino, zebra, kudu and wild dogs, and a scene depicting an elephant hunt. Mr. Reid adds that "Jinji Mavara" freely translated, would mean "many marks, lines or colours" and obviously refers to the paintings In the cave.

Speculation on the origin of the "ruins" of Inyanga is as rife and as controversial as speculation on the origin of Zimbabwe. In the opinion of some writers there is a direct connection between the two.

Theories of large scale exotic influence in the region arising, for example, from early colonization by the Phoenicians [5], from a possible Indian period at Inyanga about the time of Christ, or from subsequent Persian-Arab infiltration [6], are considered by archaeologists to have been discounted by lack of reliable evidence of occupation by any alien people7. Such theories nevertheless persist and are staunchly defended in print [5]. They add to the mystique of Inyanga.

Ruins in the vicinity of Nyahokwe HIM on Ziwa Farm below the Inyanga range, indicate the existence of a well established community between AD300 and AD1100' an Iron Age culture preceding that assigned by archaeologists to Zimbabwe. Skeletal remains (of which there have been very few indeed) have been found to be predominantly Negroid [10]. The ruined village was excavated by F. O. Bernhard who wrote a most informative paper on the subject and who has described some of the old Ziwa pottery as comparing favourably with the ceramics of much more advanced cultures11.

Among the picturesque and puzzling features of the district are the thousands of hill terraces, the wide-spread stone ruins and water furrows, and the many pits lined with stone. Some of the cleverly contrived irrigation furrows are in use to this day.

Rhodes referred to the pits as "slave pits" [12]. Many people still do so, maintaining that they were used as staging points by Arab slavers. Carl Peters, writing of them in 1902 [12], expressed the conviction that, in conjunction with the water furrows, they were used for washing quartz for gold. A. J. Bruwer [13] refers to them as (Phoenician) grain pits. To the archaeologists they are known simply as "pit structures" or "stone lined pits"" built for the purpose of housing sheep or goats and, less probably, pigs [15].

The vast areas of terraces give the impression of having supported a large population. Indeed, A. J. Bruwer and R. Gayre maintain that they served not only a local purpose but supported, agriculturally, the builders or occupiers of Zimbabwe and other related ruins all over Rhodesia. Here again, there are conflicting theories. P. S. Garlake suggests that the lowland ruins represent an elaborate form of shifting cultivation [16].

Leading through some of the terraces are stone lanes. They are generally assumed to have served as paths for livestock passing through the terraced crops, but Bruwer advances the fascinating theory that the Phoenicians used them as training tracks for the domestication of African elephants [17].

Introduction

Inyanga is an area of charm and of mystery. Rugged mountains and rolling downs combine to present an ever-changing scene. The highest mountain In Rhodesia, Inyangani, stands sentinel over far-flung peaks and valleys, impressive river gorges and waterfalls. Miles of undulating, grass-covered slopes, par¬ticularly in the higher reaches, are seasonally enriched with masses of wild flowers. Tree ferns enhance the beauty of the river courses and patches of indigenous trees, which also thrive in small clusters in protected hollows, suggest the possibility of a wealth of timber cover many years ago. Today, forests of wattle and of pine, planted in more recent times, stretch for miles. Striking boulder-topped kopjes of infinitely varied shape and formation, rich in vegetation and in Intriguing nooks and caves, feature along some of the main approaches to the mountainous area, while remnants of old settlements, stone fortifications, ancient terraces and pits, bear evidence of various cultures including some of the oldest in the country.

Nestling In the sheltered valleys or stretching over the plains of this lovely region are farm lands, both high-lying and low, orchards, plantations, tea estates and residential retreats. Man made lakes and holiday resorts help to attract the traveller, the rambler, and the fisherman. Here flow the sparkling streams which are the Mecca of the 'Rhodesian trout angler and here, in a lovely setting, lie the homes of many Rhodesians in their retirement.

The Administrative District

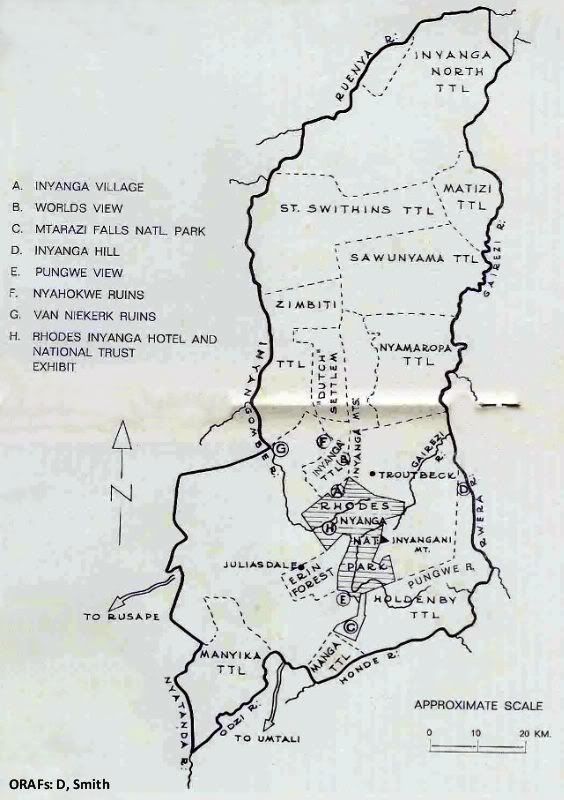

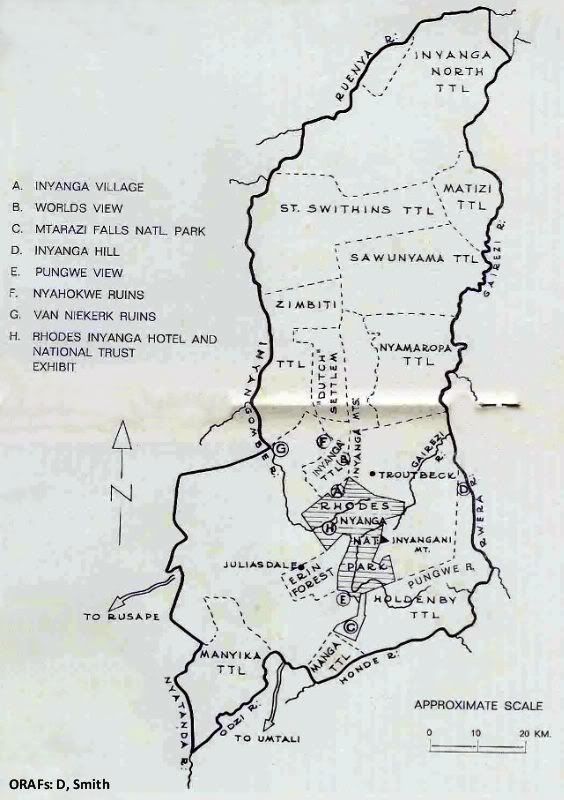

The notes in this brief section and the section which follows, being largely historical in character, refer to the administrative area of Inyanga as officially recognized until 1973, when some of the boundaries were changed. Until then the administrative district of Inyanga covered 647500 hectares (2 500 square miles). It embraced no less than ten areas of Tribal Trust Land, together with European farming land, forest reserves and National Parks, thriving villages and holiday centres.

While it is not unusual for boundaries to run along river courses, the topography of Inyanga is such that there was more than passing many miles. The district was bounded to the north by the Ruenya, and rivers such as- the Ruenya again, the Inyangombl and the Nyatanda featured prominently along its western boundary. Part of the southern boundary followed the Honde River. (Map: Pages 12 and 13)

African Tribes

The principal African tribes of the area, scattered throughout the ten Tribal Trust Lands, were the vaHwesa and vaBarwe in the north, the vaUnyama in the central region, and the vaManyika and vaBarwe in the south.

Population density ran from high in the Holdenby, Manga and Manyika tribal Trust Lands in the south, to low in the arid low- veld of the north. Altitude varied from about 600 metres in parts of Inyanga North to over 2100 metres in the highlands of Sawunyama Tribal Trust Land.

Four Chiefs and eleven Headmen held sway over 78 900 tribesmen and about 404 000 hectares (a million acres) of land.

Crops grown varied from maize and sorghum in the northern region to tea, coffee, cotton and burley tobacco in the higher rainfall central and southern regions.

Handcrafts included fine traditional blacksmithing, basket weaving and soapstone carving, and the Zuwa Weaving Centre near the Administrative Offices produced finely hand-woven wool rugs, bedspreads, table mats and other articles in traditional and modern patterns, using natural veld dyes.

Origin of Name

There are at least three slightly differing versions of the Origin of the name "Inyanga". For the one which follows, the writer is indebted to R. E. Reld.

Mr. Reid was, for some time District Commissioner at Inyanga and subsequently Provincial Commissioner for the Midlands, Ministry of Internal Affairs. He took, and still retains in retirement, a deep interest In the history of the district, and as an outstanding linguist has gained considerable knowledge of its folk lore.

Mr. Reid writes as follows:

'If you look at a map of the Inyanga district and follow the eastern boundary of Holdenby Tribal Trust Land northwards from the source of the Rwera River up past Mt. Tsuwe, you will come to a hill called Nyanga — It Is right on the international boundary and It is called Nyanga because It has two little peaks on its summit which, from a certain angle, look like the horns of a small buck . . . ("runyanga" — a horn; plural — "nyanga" . . . R.W.P.).

In the Chimanyika dialect there is a prefix "SA" which is very commonly used amongst the Vamanylka and it means "the guardian of" or "the keeper of" or someone particularly associated with a certain thirig. For instance a Kraalhead in the Inyanga Tribal Trust Land who lives, or used to live, or whose ancestors used to live, close to the mountain named Nyahokwe is called Sanyahokwe — "The guardian of Nyahokwe". And in the Inyanga North Reserve there is a great granite mountain called Nani — the Headman living near it is called Sanani . . .

Long ago, before the white man came to Rhodesia, a famous herbalist of the Barwe tribe lived at the foot of Mt. Nyanga and his name'—for the reasons given above was Sanyanga. He was a very famous doctor and people came from far and wide to consult him.

'One day Chief Mutasa, who lived at the hill called Binga Guru in what is now the Mutasa South Tribal Trust Land in Umtali district, fell ill and summoned Sanyanga to attend upon him.

'Sanyanga cured Mutasa, who was so pleased with him that he made him his court physician with the rank of Headman and gave him a "dunhu" (district) in the area hear the farm now called Sanyanga's Garden.

"When the first Native Commissioner was sent to Inyanga he established his camp and office in the vicinity of Headman Sanyanga's Kraal, which was referred to by the early European settlers as "Sanyanga's", and finally abbreviated to "Inyanga".

African Tribes

The principal African tribes of the area, scattered throughout the ten Tribal Trust Lands, were the vaHwesa and vaBarwe in the north, the vaUnyama in the central region, and the vaManyika and vaBarwe in the south.

Population density ran from high in the Holdenby, Manga and Manyika tribal Trust Lands in the south, to low in the arid low- veld of the north. Altitude varied from about 600 metres in parts of Inyanga North to over 2100 metres in the highlands of Sawunyama Tribal Trust Land.

Four Chiefs and eleven Headmen held sway over 78 900 tribesmen and about 404 000 hectares (a million acres) of land.

Crops grown varied from maize and sorghum in the northern region to tea, coffee, cotton and burley tobacco in the higher rainfall central and southern regions.

Handcrafts included fine traditional blacksmithing, basket weaving and soapstone carving, and the Zuwa Weaving Centre near the Administrative Offices produced finely hand-woven wool rugs, bedspreads, table mats and other articles in traditional and modern patterns, using natural veld dyes.

Origin of Name

There are at least three slightly differing versions of the Origin of the name "Inyanga". For the one which follows, the writer is indebted to R. E. Reld.

Mr. Reid was, for some time District Commissioner at Inyanga and subsequently Provincial Commissioner for the Midlands, Ministry of Internal Affairs. He took, and still retains in retirement, a deep interest In the history of the district, and as an outstanding linguist has gained considerable knowledge of its folk lore.

Mr. Reid writes as follows:

'If you look at a map of the Inyanga district and follow the eastern boundary of Holdenby Tribal Trust Land northwards from the source of the Rwera River up past Mt. Tsuwe, you will come to a hill called Nyanga — It Is right on the international boundary and It is called Nyanga because It has two little peaks on its summit which, from a certain angle, look like the horns of a small buck . . . ("runyanga" — a horn; plural — "nyanga" . . . R.W.P.).

In the Chimanyika dialect there is a prefix "SA" which is very commonly used amongst the Vamanylka and it means "the guardian of" or "the keeper of" or someone particularly associated with a certain thirig. For instance a Kraalhead in the Inyanga Tribal Trust Land who lives, or used to live, or whose ancestors used to live, close to the mountain named Nyahokwe is called Sanyahokwe — "The guardian of Nyahokwe". And in the Inyanga North Reserve there is a great granite mountain called Nani — the Headman living near it is called Sanani . . .

Long ago, before the white man came to Rhodesia, a famous herbalist of the Barwe tribe lived at the foot of Mt. Nyanga and his name'—for the reasons given above was Sanyanga. He was a very famous doctor and people came from far and wide to consult him.

'One day Chief Mutasa, who lived at the hill called Binga Guru in what is now the Mutasa South Tribal Trust Land in Umtali district, fell ill and summoned Sanyanga to attend upon him.

'Sanyanga cured Mutasa, who was so pleased with him that he made him his court physician with the rank of Headman and gave him a "dunhu" (district) in the area hear the farm now called Sanyanga's Garden.

"When the first Native Commissioner was sent to Inyanga he established his camp and office in the vicinity of Headman Sanyanga's Kraal, which was referred to by the early European settlers as "Sanyanga's", and finally abbreviated to "Inyanga".

The Native Commissioner's office was moved several times before it came to rest at its present site and the name followed it and was eventually applied to the whole district.'

The farm Sanyanga's Garden, mentioned in Mr. Reid's note, is within a few kilometres south-west of the Pungwe Falls. The association of this farm with the first Native Department camp is also recorded by R. Summer [2]

Inhabitants of the past.

There is evidence of very considerable settlement in days gone by, some of it of great antiquity.

Crude tools associated with the early Stone Age of some 40 000 to 50 000 years ago have been found [3] but the probes of the historian and the archaeologist have much to uncover in relation to the intervening centuries.

Some evidence of late Stone Age occupation is provided by "Bushman Paintings" not, perhaps, as numerous as in certain other parts of Rhodesia (there are large tracts without the caves and rock over-hangs favoured by those "artists") but none the less significant. C. B. Payne [4] has drawn attention to extensive paintings on the hill Nyapani in Bannockburn North, and isolated paintings in shelters near Sanyatwe and Inyanga Village.

R. E. Reid, to whom reference has already been made in connection with the origin of the name "Inyanga", has supplied the writer with a most interesting note on a cave, difficult of access, called "Jinjimavara" in the vicinity of Mt. Nani in the Inyanga North Tribal Trust Land. On its walls appear signs and symbols with possibly "magical" connotations, and numerous animal drawings including tsessebe, pig, rhino, zebra, kudu and wild dogs, and a scene depicting an elephant hunt. Mr. Reid adds that "Jinji Mavara" freely translated, would mean "many marks, lines or colours" and obviously refers to the paintings In the cave.

Speculation on the origin of the "ruins" of Inyanga is as rife and as controversial as speculation on the origin of Zimbabwe. In the opinion of some writers there is a direct connection between the two.

Theories of large scale exotic influence in the region arising, for example, from early colonization by the Phoenicians [5], from a possible Indian period at Inyanga about the time of Christ, or from subsequent Persian-Arab infiltration [6], are considered by archaeologists to have been discounted by lack of reliable evidence of occupation by any alien people7. Such theories nevertheless persist and are staunchly defended in print [5]. They add to the mystique of Inyanga.

Ruins in the vicinity of Nyahokwe HIM on Ziwa Farm below the Inyanga range, indicate the existence of a well established community between AD300 and AD1100' an Iron Age culture preceding that assigned by archaeologists to Zimbabwe. Skeletal remains (of which there have been very few indeed) have been found to be predominantly Negroid [10]. The ruined village was excavated by F. O. Bernhard who wrote a most informative paper on the subject and who has described some of the old Ziwa pottery as comparing favourably with the ceramics of much more advanced cultures11.

Among the picturesque and puzzling features of the district are the thousands of hill terraces, the wide-spread stone ruins and water furrows, and the many pits lined with stone. Some of the cleverly contrived irrigation furrows are in use to this day.

Rhodes referred to the pits as "slave pits" [12]. Many people still do so, maintaining that they were used as staging points by Arab slavers. Carl Peters, writing of them in 1902 [12], expressed the conviction that, in conjunction with the water furrows, they were used for washing quartz for gold. A. J. Bruwer [13] refers to them as (Phoenician) grain pits. To the archaeologists they are known simply as "pit structures" or "stone lined pits"" built for the purpose of housing sheep or goats and, less probably, pigs [15].

The vast areas of terraces give the impression of having supported a large population. Indeed, A. J. Bruwer and R. Gayre maintain that they served not only a local purpose but supported, agriculturally, the builders or occupiers of Zimbabwe and other related ruins all over Rhodesia. Here again, there are conflicting theories. P. S. Garlake suggests that the lowland ruins represent an elaborate form of shifting cultivation [16].

Leading through some of the terraces are stone lanes. They are generally assumed to have served as paths for livestock passing through the terraced crops, but Bruwer advances the fascinating theory that the Phoenicians used them as training tracks for the domestication of African elephants [17].

The terraces and ruins are estimated to cover something like 500 000 to 800 000 hectares18, and are scattered over areas both close to Nyahokwe (although not necessarily associated with the Ziwa culture of that site), and very much further afield. As already indicated, there are. theories of origin reaching back to the years B.C. Archaeologists however, favour the 14th -18th centuries [19], With the ruins of the uplands ante-dating those in the lower-lying country. The latter include the Van Niekerk Ruins, named after Major P. H. van Niekerk, who settled at Inyanga following service In the Matabele Rebellion and the Boer War [20]. Van Niekerk showed considerable interest in the archaeology of Rhodesia21 and assisted D. Randall-MacIver in his researches in 1905. The ruins were named after him by Randall-MacIver. They could possibly be the same extensive ruins as were briefly reported by Mining Commissioner N. Macglashlan after a visit to the Inyanga area from Umtali in 1894 [22].

The loopholes in the walls of many of the fort ruins of Inyanga are found in few other ruins in Rhodesia {23]. Of even greater rarity in the Rhodesian context is the ingenious bolt, lock and slot device incorporated in some of the stonework of the lowland ruins, whereby a timber beam could be moved backwards or forwards to open or bar the entrance and, when closed, locked in position by another beam inserted In a vertical slot [21].

Interesting exhibits of various cultures may be seen in the small field museum built by the National Museums and Monuments Commission at the Nyahokwe site.

The Portuguese must have found themselves very close to Inyanga in their early travels. Between 1511 and 1514, Antonio Fernandes, a Portuguese "degredado" undertook a series of journeys from the east coast which took him far into the interior25. Old documents indicate that he came into contact with the vaBarwe and, possibly, the vaHwesa who now inhabit the area, but it is important to note that it seems probable that these tribes were at the time resident further to the east or north-east.

Carl Mauch [26], the industrious German explorer, traversed the northern part of what is now Inyanga in June 1872, crossing the Gaerezi (travelling east) on 1st July. He wrote of alluvial gold in the area and of intriguing references, by the inhabitants, to "white men who lived in this country a long, long time ago" . . . who "dug in the stones" and who would be welcomed back to give protection against marauding tribes,

The Turn of the Century

In the early 1890's the rather inaccessible area of Inyanga began to attract the attention of the pioneers. F. C. Selous [27] wrote of the "magnificently watered . . . little known . . . very fine tract of country" to the east and south-east of the road between Salisbury and Umtali. He had, he said, travelled a good deal in that direction (he had, in fact, reached the village of Sitanda, an important chief in the Manica country, in 1878) [28], and he gave a glowing account of the extensive views from the summit of Dombo which he climbed In February 1891.

Douglas McAdam, an Umtali resident [29], is attributed with having played a prominent part in arousing initial interest in the prospect of modern-day settlement in the area. After a journey of exploration in 1892, McAdam spread the news of the attractions of this lovely part of the country, and in 1893 guided to it a party of men who thereupon pegged farms [30].

McAdam's farm was appropriately named Inyanga Farm. It was eventually bought by Rhodes.

A schedule of farms and original occupants is listed as an appendix to this article. As far as can be ascertained from one source or another, this list is applicable to the 1890's . Dates of title are not given because they do not reflect the dates on which the farms were pegged or occupied. Formal title normally replaced some other form of right of tenure such as a Certificate of Occupation. Survey dates are not a good guide either. Survey frequently took place after the occupation of the holdings, and even then not necessarily in the order in which the farms were occupied. A form of purchase-installment (quit rent) was paid in most cases. The earliest that can be traced is that paid by the Zambesi Exploration Company Limited at Mt. Dombo, with effect from January, 1892 (presumably preceding McAdam) followed by those of G. D. Fotheringhame on Fruitfield and J. Turner on "Turners" from January, 1893.

It would seem that there were no less than six members of the 1890 Column32 amongst the early landowners — B. Bradley, C. Bradley and A. Tulloch, who jointly owned the farms Inyanga Valley and Inyanga Slopes; J. Corderoy (Gaerezi and Inyangombi); W. Auret (Rhino Valley); and L. Cripps to whom, as manager of the Manhattan Syndicate of Mashonaland, the earliest official land titles in the area (other than that for Mt. Dombo) were issued in June, 1894 in respect of the farms Rupanga, Pungwe Falls, Inyawari, Iron Cliffs, Chipungu Waterfall, The Downs and Frobisher [33].

Other early landowners associated with pioneering exploits of note up to the time of McAdam's journey were J. W. Nesbitt and J. B. Moodie [34] members of the Moodie Trek as far as Fort Victoria, whence the remaining members of the Trek pressed on eastward to the Chipinga-Melsetter area. Nesbitt, who pegged the farm Warrendale, became Native Commissioner for the Umtali district including Inyanga. Moodie, who named his farm Claremont, after Mrs. Moodie's birthplace in the Cape, is credited with the distinction of having grown the first apples [36] in a district which is now noted for the quality of its fruit.

Another early landowner who distinguished himself in the sphere of fruit growing was W. Leckie Ewing of Ruparara [36].

Fruit growing was, however, not the sole, nor, probably, the predominant activity over the area as a whole. Grain crops and stock ranching commanded attention [37]. With locust scares and threats of rinderpest38, life must have been full of incident. Sheep also brought their problems.

Although Inyanga today produces fine sheep, it was years before the most suitable breeds were proved. Mrs. A. M. Harmer, a member of the Moodie family, recorded that some types of sheep imported at the time were unsuited to the indigenous grasses and to the climate[39]. Years later in 1918, the Director of Agriculture was still debating the advisability of replacing one breed with another [40]. Horses seemed at first to do well' [11] but were adversely reported on in later years [40].

Perhaps, in the midst of their tribulations, the landowners might have taken heart had they but known that after becoming an Inyanga landowner, the millionaire, the Rt. Hon. C. J. Rhodes himself, was to receive (In 1898) a rather curt note from the acting manager of the Standard Bank, Umtali, to the effect that he was overdrawn in the sum of ten pounds nine shillings and three pence [42]. It would be a little unfair, perhaps, to attribute this solely to his Inyanga enterprises!

The reference above to the late Mrs. Harmer, serves as a reminder that, as Manica Moodie, she was the first girl of European parentage to be born in Manicaland [43]. This was by no means the only "first" of its kind achieved by Inyanga landowners. A. Tulloch's eldest son, Alastair Rhodes Tulloch, was the first white child to be born in Mashonaland and was the recipient of a special land grant from Rhodes [44].

Several of the early landowners were resident in Umtali and played a useful part in the commercial, mining and social life of that community [43]. Some were also prominent in the Volunteer Forces [46] of that period of rebellion. Descendants of the Moodies 'state that they (the Moodie family) had to go into laager at Old Umtali in 1896 [69] A party including four women and twelve children reached Umtali from Inyanga for refuge on the 25th June, 1896 [47].

The loopholes in the walls of many of the fort ruins of Inyanga are found in few other ruins in Rhodesia {23]. Of even greater rarity in the Rhodesian context is the ingenious bolt, lock and slot device incorporated in some of the stonework of the lowland ruins, whereby a timber beam could be moved backwards or forwards to open or bar the entrance and, when closed, locked in position by another beam inserted In a vertical slot [21].

Interesting exhibits of various cultures may be seen in the small field museum built by the National Museums and Monuments Commission at the Nyahokwe site.

The Portuguese must have found themselves very close to Inyanga in their early travels. Between 1511 and 1514, Antonio Fernandes, a Portuguese "degredado" undertook a series of journeys from the east coast which took him far into the interior25. Old documents indicate that he came into contact with the vaBarwe and, possibly, the vaHwesa who now inhabit the area, but it is important to note that it seems probable that these tribes were at the time resident further to the east or north-east.

Carl Mauch [26], the industrious German explorer, traversed the northern part of what is now Inyanga in June 1872, crossing the Gaerezi (travelling east) on 1st July. He wrote of alluvial gold in the area and of intriguing references, by the inhabitants, to "white men who lived in this country a long, long time ago" . . . who "dug in the stones" and who would be welcomed back to give protection against marauding tribes,

The Turn of the Century

In the early 1890's the rather inaccessible area of Inyanga began to attract the attention of the pioneers. F. C. Selous [27] wrote of the "magnificently watered . . . little known . . . very fine tract of country" to the east and south-east of the road between Salisbury and Umtali. He had, he said, travelled a good deal in that direction (he had, in fact, reached the village of Sitanda, an important chief in the Manica country, in 1878) [28], and he gave a glowing account of the extensive views from the summit of Dombo which he climbed In February 1891.

Douglas McAdam, an Umtali resident [29], is attributed with having played a prominent part in arousing initial interest in the prospect of modern-day settlement in the area. After a journey of exploration in 1892, McAdam spread the news of the attractions of this lovely part of the country, and in 1893 guided to it a party of men who thereupon pegged farms [30].

McAdam's farm was appropriately named Inyanga Farm. It was eventually bought by Rhodes.

A schedule of farms and original occupants is listed as an appendix to this article. As far as can be ascertained from one source or another, this list is applicable to the 1890's . Dates of title are not given because they do not reflect the dates on which the farms were pegged or occupied. Formal title normally replaced some other form of right of tenure such as a Certificate of Occupation. Survey dates are not a good guide either. Survey frequently took place after the occupation of the holdings, and even then not necessarily in the order in which the farms were occupied. A form of purchase-installment (quit rent) was paid in most cases. The earliest that can be traced is that paid by the Zambesi Exploration Company Limited at Mt. Dombo, with effect from January, 1892 (presumably preceding McAdam) followed by those of G. D. Fotheringhame on Fruitfield and J. Turner on "Turners" from January, 1893.

It would seem that there were no less than six members of the 1890 Column32 amongst the early landowners — B. Bradley, C. Bradley and A. Tulloch, who jointly owned the farms Inyanga Valley and Inyanga Slopes; J. Corderoy (Gaerezi and Inyangombi); W. Auret (Rhino Valley); and L. Cripps to whom, as manager of the Manhattan Syndicate of Mashonaland, the earliest official land titles in the area (other than that for Mt. Dombo) were issued in June, 1894 in respect of the farms Rupanga, Pungwe Falls, Inyawari, Iron Cliffs, Chipungu Waterfall, The Downs and Frobisher [33].

Other early landowners associated with pioneering exploits of note up to the time of McAdam's journey were J. W. Nesbitt and J. B. Moodie [34] members of the Moodie Trek as far as Fort Victoria, whence the remaining members of the Trek pressed on eastward to the Chipinga-Melsetter area. Nesbitt, who pegged the farm Warrendale, became Native Commissioner for the Umtali district including Inyanga. Moodie, who named his farm Claremont, after Mrs. Moodie's birthplace in the Cape, is credited with the distinction of having grown the first apples [36] in a district which is now noted for the quality of its fruit.

Another early landowner who distinguished himself in the sphere of fruit growing was W. Leckie Ewing of Ruparara [36].

Fruit growing was, however, not the sole, nor, probably, the predominant activity over the area as a whole. Grain crops and stock ranching commanded attention [37]. With locust scares and threats of rinderpest38, life must have been full of incident. Sheep also brought their problems.

Although Inyanga today produces fine sheep, it was years before the most suitable breeds were proved. Mrs. A. M. Harmer, a member of the Moodie family, recorded that some types of sheep imported at the time were unsuited to the indigenous grasses and to the climate[39]. Years later in 1918, the Director of Agriculture was still debating the advisability of replacing one breed with another [40]. Horses seemed at first to do well' [11] but were adversely reported on in later years [40].

Perhaps, in the midst of their tribulations, the landowners might have taken heart had they but known that after becoming an Inyanga landowner, the millionaire, the Rt. Hon. C. J. Rhodes himself, was to receive (In 1898) a rather curt note from the acting manager of the Standard Bank, Umtali, to the effect that he was overdrawn in the sum of ten pounds nine shillings and three pence [42]. It would be a little unfair, perhaps, to attribute this solely to his Inyanga enterprises!

The reference above to the late Mrs. Harmer, serves as a reminder that, as Manica Moodie, she was the first girl of European parentage to be born in Manicaland [43]. This was by no means the only "first" of its kind achieved by Inyanga landowners. A. Tulloch's eldest son, Alastair Rhodes Tulloch, was the first white child to be born in Mashonaland and was the recipient of a special land grant from Rhodes [44].

Several of the early landowners were resident in Umtali and played a useful part in the commercial, mining and social life of that community [43]. Some were also prominent in the Volunteer Forces [46] of that period of rebellion. Descendants of the Moodies 'state that they (the Moodie family) had to go into laager at Old Umtali in 1896 [69] A party including four women and twelve children reached Umtali from Inyanga for refuge on the 25th June, 1896 [47].

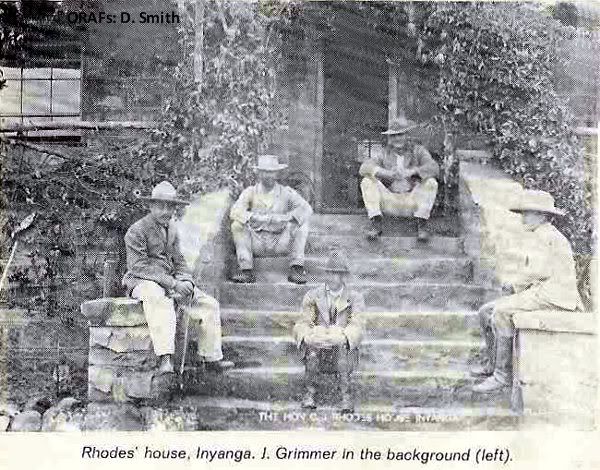

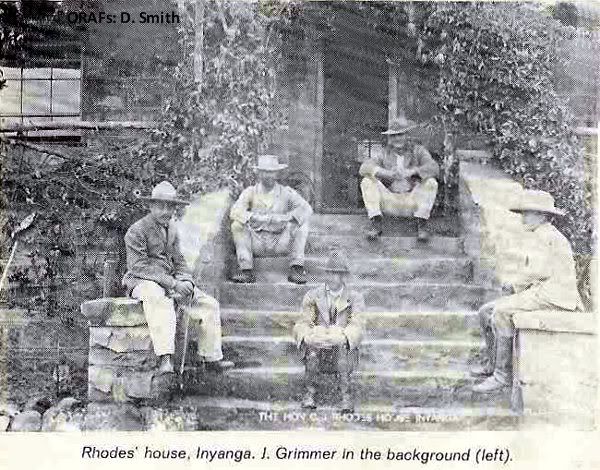

The Inyanga homestead of one of the Umtali residents, G. D. Fotheringhame, the owner of Pungwe Source and Fruitfield, was mentioned in the press in 1895 as a "commodious" residence [48]. Rhodes bought both farms and it is Fotheringhame's homestead on Fruitfield which is thought to have been occupied by him later, and around which the Rhodes Inyanga Hotel was ultimately built [49]. Rhodes is said [50] to have employed, after his purchase, a stonemason by the name of Dickie Marks from Umtali, to do further building on the site. There is an architect's certificate on record [51] authorising the payment to R. Marks of two hundred and thirty- three pounds ($466) on behalf of Rhodes "under the conditions of contract". Judging by early photographs of the homestead and its surrounds, the present substantial stone barn, with loft, originally used as a stable, probably featured among the additions erected by Marks. So unexpectedly imposing was it to visitors to the rugged fastnesses of Inyanga that it was described by one enthusiast at the time as the best building in Rhodesia [52]. Another builder and stone-mason by the name of G. W. Jonas was sent up from South Africa in 1899 and worked on the Estate until 1901[52]. To him must go the credit for some of the stonework on the hotel site.

Whether resident at Inyanga or not, these pioneering land¬owners were prepared to take active steps to remedy the comparative isolation of their farms, and the building of the road from Umtali was an excellent example of self-help [53]. It was built in the main in 1895 under an arrangement whereby "Government", through the agency of G. Pauling, the Commissioner of Works, undertook to supply labour and materials such as tools and explosives. A committee of landowners was responsible for the raising of funds at three pounds ($6) per 1 500 morgen (about 1 285 ha), and for the implementation of the road work. The work was supervised by Fotheringhame.

In addition, the re-alignment of the transcontinental telegraph took place in those early days [54]. The old line, spanning the country between Salisbury and Mount Darwin, crossed some unhealthy territory. The timber poles had not proved durable; nor had they been treated with marked respect by tribesmen during the days of the rebellion. The new line was routed from Umtali via Inyanga to the Zambesi at Tete, and thence to Nyasaland, with the ultimate object of connecting up with Uganda and Egypt. Arrangements for this project were entrusted by Rhodes to Jameson in 1897, the latter having just returned to Rhodesia depressed both in spirit and in health after a spell of Imprisonment in England for his part in the Jameson Raid [55]. G. H. Tanser records that Jameson set up a store for the project on the site of the present Anglers Rest Hotel [56]. The resilient and adventurous Jameson, after negotiating with the Portuguese for the telegraph route, embarked on an arduous journey by dugout down the Zambesi from Tete to the sea [55].

Inyanga's Van Niekerk is reported to have played a part in the installation of the telegraph offices at Inyanga and at Tete, thereafter proceeding to Blantyre [57].

By April 1898, communication with Blantyre was established [58].

Government officials of the period must also have undertaken some challenging trips, and one imagines that the most knowledgeable of all as regards both the glory of the views and the difficulties of the terrain must have been H. J. Pickett, who surveyed the great majority of the farms and ultimately became an Inyanga landowner himself, when he took over the farm Albany. In his surveys he had to contend not only with mountains and gorges (and one can say with confidence, rain and mist), there was also the sensitive question of the border with Portuguese East Africa to be taken carefully into account. Some 3 500 morgen (3 000 ha) of the Inyanga Block were found to intrude into Portuguese territory [33].

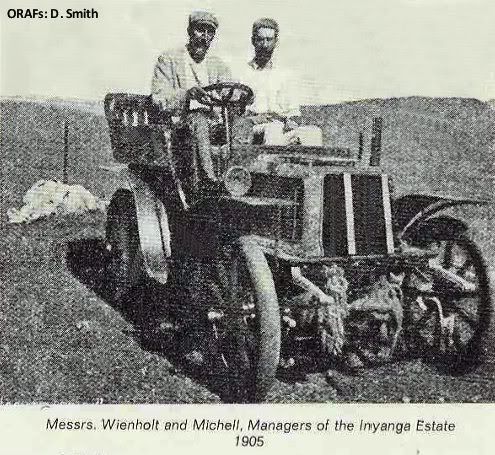

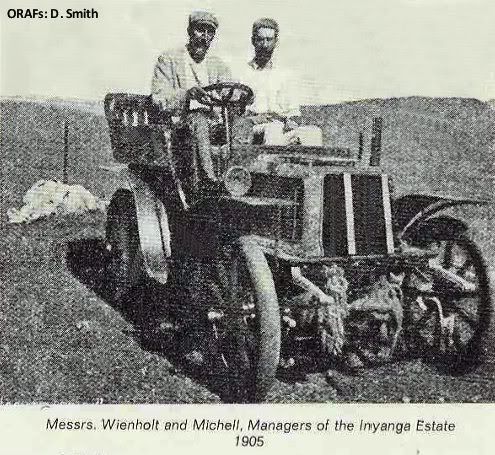

The administration of African affairs, police work, and other services also demanded some challenging and wide-ranging journeys. At first these involved tours of duty from temporary camps and from centres such as Umtali. There is a reference in the records, to a Police station in the region in July, 1898 and Native Department officials operated from hut camps. The first Native Commissioner with responsibility for Inyanga from Umtali headquarters was, nominally at least, E. H. Compton Thomson. However, after a spell of duty of less than three months between September and December, 1894, Compton Thomson was transferred to the Range and it is his successor J. W. Nesbitt (owner of the Inyanga farm Warrendale) who is generally acknowledged as the first Native Commissioner for Inyanga, although stationed at Umtali. After an early visit In his official capacity he sent to Inyanga, as resident Assistant Native Commissioner, J. W. Gray, who was there until 1899. The first substantive Native Commissioner resident in the area was T. B. Hulley, who was transferred there temporarily from Umtali in 1902 and returned to his former station in 1903. By this time the Native Department had moved from the vicinity of Sanyangas Garden. Hulley had built a new hutted camp and his office was a small cottage lent by Weinholt and Michell, managers of Rhodes Estate [60].

Rhodes and Inyanga

Rhodes' interest in Inyanga was inspired by J. G. (later Sir James) McDonald, who became one of his Trustees, and wrote one of the most popular of Rhodes' many biographies.

In 1896, fresh from his historic "indabas" in the Matopos with the rebellious Matabele, but still beset by problems arising from the Jameson Raid and by anxieties arising from the Mashona Rebellion, Rhodes visited Inyanga for the first time61. He gloried in the change of scene, was deeply impressed with the grandeur and promise of the area, and instructed the purchase of up to 100 000 acres (about 40 000 hectares) [62].

He visited Inyanga again in 1897, and because of illness stayed for some time. Jameson, returning from his journey down the Zambesi following the telegraph line negotiations, immediately took over attendance oh him and during the long weeks of recuperation the two men became fully reconciled; a blessing to both after the strain to which their friendship had been Subjected by the Raid and its consequences. Full of schemes for the running of livestock and experiments with a variety of crops, ideas which found expression in the subsequent activities of his managers and in the terms of his will some five years later Rhodes was able, during his recovery, to spend some time in developing his ideas further, and in getting to know the area more intimately by riding over it [63]. Colvin writes of him that he and Jameson explored the country with schoolboy zest [55] and McDonald records that he spent many hours with the local farmers, never grudging the time given to finding a solution to their difficulties [64].

Rhodes' final visit to Inyanga was in 1900 after his frustrating experience in the siege of Kimberley [65]. For the last time, in July and August of that year, he immersed himself in the tranquility of the area he had grown to love.

His early managers at Inyanga were J. Grimmer and J. Norris [66]. For a considerable period they were together on the Estate an arrangement not entirely to the liking of either of them. Like many farmers before and since, they went through some torrid times. A doleful report by Norris to Rhodes in May, 1899, refers to deaths among the livestock, failure of the wheat and oats crops due to bad seed; barley and vegetables swamped by heavy rains; potatoes diseased; fig and pear trees disappointing. Six months

before, the locusts had "eaten everything off". Rhodes' impatience at this time engendered a certain amount of bitterness [52]. Nevertheless they persevered. By 1901, under their direction, an afforestation programme was under way in the orchards about 1 400 fruit trees were doing well and were expected to bear In that year; among the sheep it had been found that Merinos were not thriving but that Cape sheep crossed with Persian rams did better; and of the 400-500 head of cattle which were being ranched, Herefords and Devon’s seemed better suited than Shorthorns, Frieslands' and other stock [68].

It was during Norris' period as manager that J. C. Johnson, his brother-in-law (subsequent owner of Glen Spey and Oakvale) is reputed [69] to have brought up from the Cape, at Rhodes' instigation, the acorns from which were planted the oak trees which grace the entrance to Rhodes Inyanga Hotel. Previous consignments of acorns had failed.

Norris later farmed on his own account [33] in the Inyanga area for a few years (acquiring Sophiendale and, for a time in partner¬ship with Johnson, Glen Spey), before settling permanently in or near Umtali (farms Agnes, gifted to him by Rhodes [42]; and later Devonshire).

Grimmer, whose management of Rhodes' farms at Inyanga formed only a minor part of a wide range of services to his chief, was left a large legacy when Rhodes died, together with the use of the Inyanga farms for life [70]. He did not live to enjoy these expressions of affection and gratitude. He contracted fever at the time of Rhodes' funeral and died two months later [71].

Twenty-five years later, when E. B. Allen became manager of Rhodes Estate, the older Africans still called the estate "Grimmer" [72]. It is known in fact that this old association of Grimmer's name with the land which he and his successors developed, persisted at least Into the 1950's [73].

The farms purchased by Rhodes in his quest for 100 000 acres are listed in a second appendix to this paper. For the total of 38 800 ha [74] (just under 96 000 acres), the price paid was 15 260 pounds sterling [52] (say $30 520 although, of course, this bears only the remotest relationship to the value of the pound sterling in those days). Le Sueur, one of Rhodes' Private Secretaries, mentions a sum of 19 500 pounds sterling for some 81 000 morgen" (over 69 000 ha) but in the preface to his book he admits that it was written largely from memory. Certainly the farms purchased in the Inyanga area, even with the addition of three lying a little outside the district boundary (Faith, Hope and Agnes) did not cover anything like 81 000 morgen. Some of the farms which interested Rhodes did not come his way and this might easily have lent confusion to Le Sueur's recollections. For example J. B. Moodie of Claremont declined to sell, and so at the time did Nesbitt on Warrendale. Both considered that they had been let down in the matter of land grants at the time of the Moodie Trek. (There was, nevertheless, warm friendship between Rhodes and the Moodie family in later days3y n). Rhodes also toyed with the Idea of buying the huge Inyanga Block (73 600 morgen") which in more recent years, under new ownership and subdivision, has been the scene of very considerable and, in part, spectacular development.

One of Rhodes' dreams for the future was that there would One day be a sanatorium at Inyanga. The site he had in mind was on the boundary of Claremont, just off the Pungwe road [77]. Another of his wishes was to include within his land acquisitions the magnificent Pungwe Falls, but later it was found that they were just outside the southern boundary of his Estate. This was eventually remedied when (in 1938) a small area surrounding the Falls was purchased and was incorporated in the Estate [78]. In the meantime the Trustees had added to the Estate, Nesbitt's farm Warrendale and Timaru, a farm in the Rusape district [74], and all these acquisitions completed the complex of holdings known today as Rhodes Inyanga Estate.

Rhodes not only farmed his own property; he also organised the settlement of a number of families at Inyanga, on what has become known as the Dutch Settlement [75], although there are in fact as many traditionally English names in the block as there are Afrikaans ones. The area concerned lies to the north of the Estate and to the north of Inyanga Village, and it provides an interesting contract to the high-lying and broken country which forms a considerable part of the Estate itself.

On Rhodes' death, his Inyanga Estate was bequeathed to the people of Rhodesia in the following terms: "I give free of all duty whatsoever my landed property near Bulawayo . . . and my landed property at or near Inyanga ... to my Trustees . . . upon trust that my Trustees shall in such manner as in their uncontrolled discretion they shall think fit, cultivate the same respectively for the instruction of the people of Rhodesia . . . For the guidance of my Trustees I wish to record that in the cultivation of my said landed properties, I include such things as experimental farming, forestry, market and other gardening and fruit farming, irrigation and the teaching of any of those things [70].

Wide range of early agricultural experiments

'

'

Change of Policy

Experiments of one sort or another continued, however. Cattle were run on the Estate for some time88. Attempts were made to Introduce game birds. All the English pheasants introduced at One stage were killed by leopards [87]. So were the Chikor, the Indian partridge [88]. Experimental plots, of blackberries, raspberries, strawberries, currants and gooseberries were established, and trial plantings of nut-bearing trees were also made [87].

REFERENCES

The list of references contains several abbreviations, the key to which is as follows:

"T. W. Baxter/E. E. Burke (1970):

"Guide to the Historical Manuscripts in the National Archives of Rhodesia.

"F. O. Bernhard (1960)

“"The Ziwa ware of Inyanga" NADA Vol. 38(1961): pp 84-92.

"F. O. Bernhard (1964):

"Notes on the Pre-Ruin Ziwa Culture of Inyanga"; Rhodesiana: No. 11 Dec. 1964. pp 22-30

"A. J.. Bruwer (1965)"

"Zimbabwe, Rhodesia's Ancient Greatness" Hugh Keartland.

"T. V. Bulpin (1965)" "P. S. Garlake"

'To the Banks of the Zambezi" Nelson.

“P.S. Garlake”

A Guide to the Antiquities of Inyanga" published by Historical Monuments Commission.

"P. S. Garlake (1970)"

"The Zimbabwe Ruins re-examined" Rhodesian History. Vol. 1. pp 17-29.

"R. Gayre (1972)"

R. Gayre of Gayre. "The Origin of the Zimbabwean Civilisation" Galaxie Press.

"Mrs. A. M. Harmer"

Archives interview ORAL/HA6

"G. lie Sueur"

"Cecil Rhodes". John Murray, London, 1913

"Carl Mauch"

The Journals of Carl Mauch 1869- 1872" Transcribed from the original by Mrs. E. Bernhard. translated from the German by F. 0. Bernhard. Edited by E. E. Burke. National Archives of Rhodesia 1969.

"J. G. McDonald (1941)"

'Rhodes—A Life" Chatto & Windus 6th Edition.

"D. Randall-Maclverers "

D, Randall-Maclver during British Assn. visit quoted in "The African World" Vol. 12. Sept. 1905.

J. B. Moodie"

"'Dr. Carl Peters (1902)"

refers to Appendix to Archives Interview. ORAL/HA6.

Dr. Carl Peters (1902)

"The Eldorado of the Ancients"

George Bell &Sons.

R/A"

"The Rhodesia Advertiser".

"R. Summers (1958)"

"Inyanga — Prehistoric Settlements in Southern Rhodesia" Cambridge University Press:

"R. Summers (1971)"

"Ancient Ruins and Vanished Civilizations of Southern Africa" T. V. Bulpin.

"U/A"

"The Umtali Advertiser".

1. Contributed by District Commissioner's Office, Inyanga.

2. R. Summers (1958); p. 6.

3. P. S. Garlake, p. 5.

4. Personal correspondence! C. B. Payne. Officer in Charge, Horticultural Experiment Station, Inyanga.

5. e.g. T. Bent as quoted by R. Summers (197,1), p. xvl; Also A. J. Bruwer (1965).

6. H, Von Sicard "Tentative Chronological Tables" NADA 1946, pp. 30/31; Similar theory In "Southern Rhodesia" 1929, p. 51.

7. D. Randall-Maclver, p. 258; P. S. Garlake (1970); R. Summers (1971), pp. 102/103.

8. e.g. J. E. Mullan 1969, "The Arab Builders of Zimbabwe" Rhodesia Mission

Press; R. Gayre (1972).

9. Garlake, pp7,25. F.O. Bernhard (1964) pp 28-30

10. P. S. Garlake, p. 25; F. O. Bernhard (1964), p. 28; H. De Villiers in "The South African Archaeological Bulletin" Vol,, xxiv (Parts III and IV) No's 95 and 96.

11. F. O. Bernhard (1960), p. 89; F. O. Bernhard (1964), p. 23.

12. Dr. Carl Peters (1902), pp. 170; 177/178.

13. A. J. Bruwer (1965), p. 111.

14. P. S. Garlake,, p. 14; R. Summers (1,971), p. 33.

15. R. Summers (1971), p. 153.

16. A. J. Bruwer (1965). p.26; R, G$ye (1972), p. 1?6; P. S- Garlake, p. 17.

17. A. J. Bruwer (1965). p: 20.

18. R. Summers (1958). p. 1.

19. P.S. Garlake. p. 7; R. Summers (1. 971) pp: 103 and 107.

20. T. V. Bulpin (1965), pp. P. S. Garlake, p; 17.

21. T. W. Baxter/E. E. Burke (1970), p, 485.

22. U/A 4/12/1894.

23. R. Summers (1971) p 31

24. R. Summers (1971) pp 35/36

25. R. W. Dickinson: "Antonio Fernandes— a re-assessment", Rhodesiana No. 25. 1971: pp. 45-52

26. Carl Mauch, pp. 234/235.

27. F. C. Selous "Travel and Adventure in South East Africa" Rowland Ward & Go. Ltd., 1893, pp. 328/329.

28. T. W. Baxter/E. E. Burke (1970), p. 423.

29. Several references In U/A and R/A; more specifically R/A 24/2/1898.

30. J. B. Moodie; T Bulpin (1965), p. 372.

31. Archives S 253(3) and Archives Ledger 7/12/23; Registry of Deeds; Survey Notices In U/A and R/A, e.g. U/A 16/10/1894.

32. Medal Roll: Pioneer Column and Police: 1890.

33. Archives S 253(3); Archives Ledger 7/12/23.

34. J. B. Moodie; Moodie Trek pps, Archives L2/2/95/21.

35. Asst. Dis. Comm. Inyanga — Personal communication; U/A 15/7/95 R/A 28/2/96.

36. C. B. Payne "'What happened to Wienholt?" in Inyanga Show Catalogue 1972, pp. 7/8; W. Leekle-Ewlng In Rhod. Agric. Jnl. Vol 5, 1907-8; pp. 223-228.

37. Archives NO. 5/1/1; R/A 24/1/1896.

38. R/A various, e.g. 6/8/1897 and 15/10/1897; Mrs. A, M, Harmer.

39. Mrs. A. M. Harmer.

40. Archives T 2/29/57.

41 R/A 17/3/1898.

42. Archives-DT 2/8/11.

43. Mrs. A: M. Harmer.

44. T. W. Baxter/E. E. Burke (1970), p. 473.

45. Numerous references in U/A and R/A 1893-1900.

46. R/A 30/10/1896,12//2/1897; Archives V.A. 1/1/1.

47. B.S.A. Company Report on the ''Native Disturbances In Rhodesia, 1896-97", p. 65.

48. R/A23/9/1895.

49. T. V. Bulpin (1965), p. 378; J. B. Moodie; Rhod. Agric. Jnl. Vol. 36, 1939, p. 431

50. The Rhodesia Herald, 9/3/1959.

51. Archives DT 2/8/11.

52. Archive's Microfilm MF 207.

53. U/A 4/6/1895; R/A 23/9/1895.

54. R/A 27/1/1898; 3/3/1898; J. G. McDonald (1941). p. 282.

55. Ian Colvin "The' Life of Rhodes" Vol II. Edward Arnold & Co 1922 pp, 173- 176

56. "Tony" Tanser: "Rhodes and Inyanga" in Rhodesia Calls Jan-Feb 1974 pp 15-22

57. R/A 27/1/98.

58. R/A/ 27/4/98.

59. R/A 15/7/98.

60. Archives NUA 2/1/1 - 2/1/4 and T 1/2/3 and 1/2/4.

61. J. G. McDonald (1941), p. 216, R/A4/12/1896; J. B. Moodie.

62. J. G. McDonald (1941), p. 217.

63. R/A 1/10/1897, 8/10/1897, 15/10/1897, 29/10/1897, 12/11/1897; J. G. McDonald (1941), pp. 287/8; P. Jourdan "Cecil Rhodes — His Private Life"; John Lane "The Bodley Head" 1910, pp. 55/56.

64. J. G. McDonald (1941), p. 284.

65. J. G. McDonald (1941), pp. 321-328, 344.

66. J. G. McDonald (1941), p. 338; T. W. Baxter/E. E. Burke (1970) p. 354; Archives NO. 5/1/1; Archives Microfilm MF 207.

67. J. G. McDonald (1941), p. 365.

68. "Rhodesia" Vol. 8, 1901, p. 357.

69. Archives WO 5/9/1.

70. "Will and Codicils of the Rt. Hon. Cecil John Rhodes", University Press Oxford 1929.

71. G. Le Sueur: pp. 193-197.

72. Letter from Mrs. E. Allen in response to questionnaire. (Archives).

73. C. B. Payne: Personal communication.

74. Deeds Registry.

75. G. Le Sueur: p. 166.

76. J. B. Moodie.

77. R. N. Hall "A Region of Mystery" in Pall Mall Magazine, Sept. 1905, pp. 353- 358; Mrs. A. M. Harmer.

78. J. G. McDonald (1941), p. 217; Rhodesia Agricultural Journal Vol. 36, 1939. p. 431.

79. R. Summers (1958), p. 6.

80. F. E. Wienholt; Article in "South Africa" Vol. 3, July/Sept. 1905, pp. 272-274.

81. Archives NUC 7/2/1.

82. Archives T 2/29/57.

83. Archives G 1/7//2/5.

84. Archives T 2/29/57; J. W. Barnes; Archives Interview ORAL/BA 3.

85. Archives NO. 5/1/1.

86. J. W. Barnes: Archives Interview ORAL/BA 3.

87. Rhodesia Agricultural Journal Vol. 36, 1939, pp. 430-435.

88. Personal communication: G. M. McGregor.

89. C. N. Hayter in Rhodesia Agricultural Journal Vol. 51 of 1954, pp. 187-192.

90. Ministry of Lands: Personal communication.

91. Guide to Rhodes Inyanga Experiment Station p. 3.

92. G. M. McGregor: Oral communication.

93. R/A 2/4/1895.

94. P. S. Garlake, p. 25.

APPENDIX 1

The following farms in the district appear from old records to have been settled in the 1890

Farm: Aberdeen*. Owner: J. G. McDonald

Farm: Albany. Owner: H. K. Brown

Farm: Barrydale (D/S). Owner: D'Urban Barry

Farm: Bideford (R). Owner: 0. J. Morris

Farm: Britannia : Owner: J. A. Stevens

Farm: Cheshire (D/S). Owner:Estate W. Gambell

Farm: Chipazi Owner. J. S. Maritz

Farm: Chipunga Waterfall. Owner: Manhattan Syndicate of Mashonaland Ltd.

Farm: Claremont. Owner: J. B. Moodie

Farm: Doornhoek (D/S). Owner: C. J. Strydom

Farm: The Downs. Owner: Manhattan Syndicate of Mashonaland Ltd.

Farm: Erin (R). Owner: E. Vigne

Farm: Flaknek (D/S). Owner: J. N. Strydom

Farm: Foxhill. Owner: Rhodesian Exploration & Development Co. Ltd.

Farm: Frobisher. Owner: Manhattan Syndicate of Mashonaland Ltd.

Farm: Fruitfield (R). Owner: G. D. Fotheringhame

Farm: Gaerezi (R). Owner: J. Corderoy

Farm: Glen Spey. Owner: J. W. Hudson

Farm: Holdenby**. Owner: Matabeleland Exploring Syndicate Ltd.

Farm: Inverness**. Owner: Scottish African Corporation Ltd.

Farm: Inyanga (R). Owner: D. McAdam

Farm: Inyanga Block. Owner: Anglo French Matabeleland Co. Ltd.

Farm: Inyanga Slopes (R). Owner: B. and C. K. Bradley and

Farm: Inyanga Valley (R). Owner: A. Tulloch

Farm: Inyangombi (R). Owner: J. Corderoy

Farm: Inyawari. Owner: Manhattan Syndicate of Mashonaland Ltd.

Farm: Iron Cliffs. Owner: Manhattan Syndicate of Mashonaland Ltd.

Farm: Lawley's Concession. Owner:A. L. Lawley followed by Monomatapa Development Co.

Farm: Liverpool. Owner: Manhattan Syndicate of Mashonaland Ltd.

Farm: London. Owner: Manhattan Syndicate of Mashonaland Ltd.

Farm: Lucan. Owner: White's Syndicate Ltd.

Farm: Milton. Owner: M. S. Tait

Farm: Mt. Dombo. Owner: Zambesia Exploring Co. Ltd.

Farm: Mt. Pleasant (D/S). Owner: W. Brown

Farm: Nyagadzi. Owner:Goldfields of Matabeleland Ltd.

Farm: Placefell (R). Owner: J. W. Pattinson

Farm: Pommeru. Owner: C. G. Dabis

Farm: Pungwe Falls (Part R). Owner: Manhattan Syndicate of Mashonaland Ltd.

Farm: Pungwe Source (R). Owner: G. D. Fotheringhame

Farm: Rathcline. Owner: Rathcline Syndicate Ltd.

Farm: Reenen. Owner: J. A. Muller

Farm: Rhino Valley (D/S). Owner: W. H. Auret

Farm: Rupanga. Owner: Manhattan Syndicate of Mashonaland Ltd.

Farm: Ruparara. Owner: W. Leckie Ewing (Manager, Norman McDonald)

Farm: Sanyanga's Garden. Owner: F. H. Barber

Farm: St. Swithins**. Owner: Chartered Goldfields Ltd.

Farm: St. Triashill. Owner: Trappist Community of Marianshill near Pinetown, Natal

Farm: Shitowa. Owner: F. H. Barber

Farm:Sophiendale. Owner; A. Buring

Farm: Sterkstrbom (D/S). Owner: R. Botha

Farm: Summershoek (D/S). Owner J. Bekker

Farm: Turners (D/S). Owner J. Turner:

Farm:Warrendale (R). Owner J.W. Nesbitt

Farm:Wheatlands (D/S). Owner J.B.J. Barry

Farm:Wicklow (R): Owner. F. Thompson

Farm:Withington (R)***. Owner: W. G. Holford

Farm:York. Owner: Manhattan Syndicate of Mashonaland Ltd

* Appears to have reverted to B.S.A. Company

** Now wholly or partly Tribal Trust

*** Originally called "Holford".

(D/S. Signifies Dutch Settlement

(R) Bought by Rhodes or by Rhodes Trustees

APPENDIX II FARMS IN THE INYANGA AREA PURCHASED BY RHODES

Inyanga Farm

Bought from: D. McAdam:

Extent in hectares: 1 580

Purchase Price in Pounds Sterling: 1 000

Gaerezi Farm

Bought from J. Corderoy:

Extent in hectares: 1 175

Purchase Price in Pounds Sterling 3 000

(Price Includes Inyangombi)

Inyangombi Farm

Bought from J. Corderoy

Extent in hectares 6 085

Purchase Price in Pounds Sterling See Gaerezi

Inyanga Valley Farm

Bought from Bradley Bros

Extent in hectares: 1 941

Purchase Price in Pounds Sterling 550

Inyanga Slopes Farm

Bought from Bradley Bros and A. Tulloch:

Extent in hectares: 1 448

Purchase Price in Pounds Sterling 550

Bideford Farm

Bought from O. J. Morris:

Extent in hectares 1 836

Purchase Price in Pounds Sterling 500

Erin Farm

Bought from E. Vigne

Extent in hectares 6 106

Purchase Price in Pounds Sterling 2 831 and 10/-

Withington Farm

Bought from W. G. Holford

Extent in hectares 1 298

Purchase Price in Pounds Sterling 250

Wicklow Farm

Bought from F. Thompson

Extent in hectares 1 893

Purchase Price in Pounds Sterling 400

Placefell Farm

Bought from J. W. Pattinson

Extent in hectares 1 699

Purchase Price in Pounds Sterling 700

Fruitfield Farm

Bought from G.D. Fotheringhame

Extent in hectares 2 730

Purchase Price in Pounds Sterling 1 600

Pungwe Source

Bought from G. D. Fotheringhame

Extent in hectares 1 284 for 675 Pounds Sterling

and Public Auction 7 704 hectare for Pounds Sterling 3 035

and BSA. CO. 1 964 hectare for Pounds Sterling 172 and 1/-

Total Hectares 38 743 Purchase Price in Pounds Sterling 15 263 and 11/-

* An additional three hundred and ninety-two pounds was claimed by the seller and correspondence hints that It was paid, but no such payment was reflected In the title deeds.

** Four thousand pounds in all was paid to Fotheringhame for Fruitfield and his section of Pungwe Source and other assets Including the house around which the Rhodes Inyanga Hotel was later developed.

*** This section of Pungwe Source remained unclaimed and unoccupied after the rest of the block consisting of seven farms had been bought by Rhodes, and It was slid to him at one shilling and sixpence par morgen (17 and 1/2 cents per hectare).

End of Article

Back Cover

FOOTNOTE

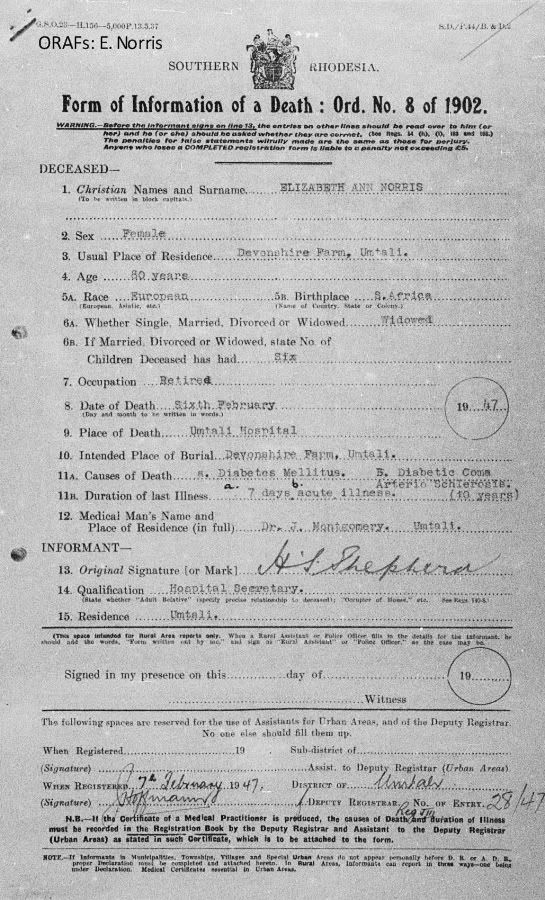

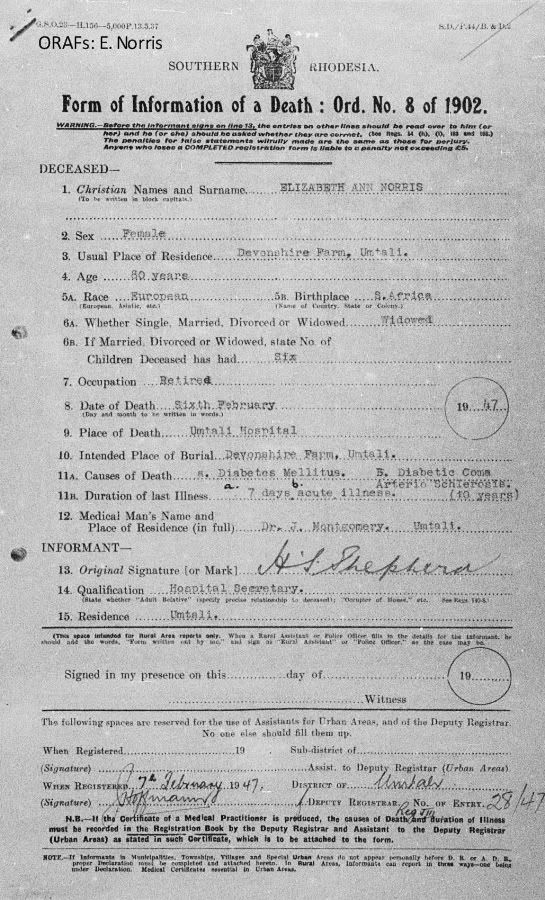

The Norris Connection

In this article there are references to John Norris and as all my work on Rhodesia are completed to leave a legacy of Rhodesia to my children, Denise and Paul I ask all to please bear with me as I include a bit on the Norris family role in the Eastern Districts of Rhodesia.

John Norris and Elizabeth Norris died on Devonshire Farm. I am currently trying to establish the dates of death. They were buried on Devonshire in an area we referred to as "The Top Lands"

During the period late 1960's the Top Lands were sold to Liebiegs and they used this as an experimental farm. With this, John and Elizabeth were exhumed and laid to rest in the Umtali Cemetery.

Denise re-compiled the content of a newspaper cutting in her possession in Canada on the death of John Norris. There is no daye and it is thought to be either the Umtali Post or Rhodesia Herald.

It reads:-

JOHN NORRIS DEAD

FORMER VALET OF RHODES

Salisbury, Wednesday ??

Mr. John Norris of Devonshire Farm, Umtali, died at his home last night after a long illness.

The last survivor of those who knew Rhodes really intimately, Mr. Norris was for eight years his personal servant during Rhodes's greatest years and, though the bitter years of his fall, Mr. Norris was staunch

to his master's memory throughout his life. In the dining-room of his house hung a large signed photograph of Rhodes, which several of the pictures on the walls and various knick-knacks were presents from

Rhodes to Mrs. Norris.

Also in a storeroom Mr. Norris had a large collection of letters written to and by Rhodes, none of them perhaps of great historical value but carefully preserved through the years as a token of respect and regard he had for his master.

He refused to read books on Rhodes written by people who had not known him and to see the "Rhodes" film. In short, if ever a man was a hero to his valet, Rhodes was to Norris.

HE MET RHODES.

Born at a place within a stone throw of Rhodes's birthplace, Norris had to seek his own living at the age of 12, and four years later, out of work and penniless, enlisted in the Inniskilling Dragoons. After ----- months training he was drafted to South Africa, arriving at Cape Town in the Grantully Castle on December 6, 1884. He first me Rhodes in 1885 when he was in Bechuanaland as personal servant to Sir Charles Warren. Five years later, when he obtained his discharge, Norris met Rhodes again and was offered a position to accompany him with the Pioneer Column to Rhodesia. Other things, intervened, and

Rhodes became Prime Minister f the Cape, retaining Norris as his servant. He remained with Rhodes at Groote Schuur till October, 1898, when was he was sent up to Inyanga, in Rhodesia to manage Rhodes's experimental farm, on which he had poured out a great deal of money.

The year before, Norris had some months at the Matope estate in Matabeleland. He remained in Inyanga for four or five years and in 1907 commenced farming very close to Umtali. Here he built a magnificent dairy farm, and was freely recognised as one of the more progressive farmers in the district.

At one time Mr. Norris bred sheep and won a cup at the Salisbury Show with some of his exhibits, but gave up on this cult. He once owned other holdings in the Umtali area but he disposed of them in order to concentrate on intensive farming at Devonshire. He took a deep interest in agricultural matters, and was a foundation member of the Umtali Agricultural Society, and for many years a member of the committee.

A FINE SHOT.

Mr. Norris was an exceptionally good shot, especially at bird. In the Inniskillings he was one of the marksmen in the regiment, and was in the regimental shooting team.

Mr. Norris was married in 1891 to Miss Elizabeth Johnson, of Cape Town, and had issue three sons and three daughters. The eldest son,Mr John Norris, proceeded overseas and joined the King's Royal Rifles. He was a sniper, and was killed at Loos in 1916.

Mr. Norris naturally could relate the most, interesting stories of Rhodes. His principal recollections of Rhodes was that he did everything to the advancement of South Africa, the Empire, and humanity, and nothing for himself. Rhodes treated him like a son, and told him he was to apply to his trustees for help if in any need. He told Mr. Norris this in the presence of Alfred Beit, but Mr. Norris never felt the necessity of approaching the trustees, simply because he had made good by his own ability.

HIS HERO.

The following remarks of his throw interesting light on Rhodes and in particular illustrate the latter's extreme consideration for those who worked well for him:

"What manner of man was he to work for? Well, there is a saying a man is a hero to valet. This I do not agree with; at any rate he was my hero and baas, very considerate if you worked hard but not otherwise:

if he disliked anyone he was very hard, and it was useless to try to please him. At times he was very irritable with everyone, but afterwards always made up for it by being very kind, especially if he had really upset anyone.

"Speaking of Rhodes's friends, it was very hard to give any impression on Rhodes and Jameson as they stood ---- alone in their relations to one another. He often said "Jameson is one in a million." The only thing I cannot imagine is Rhodes and Jameson squabbling; they were dedicated to one another.

Although I have read nasty remarks of Milner towards Rhodes, of one thing I am positive, Milner did not have a more loyal follower that Rhodes. He was one of the very few men whom I did not hear Rhodes speak against. This loyalty existed until the last year of his life, of which I had proof on his last visit to Rhodesia, when he spent three days with me in Inyanga, and he was annoyed at the Cape elections, and dictated a telegram to me to end saying he only insisted on them supporting Milner's policy. Rhodes was not the man to hide his dislike of any person to me. His likes and dislikes were more often than not extreme; if he really cared for anyone he always overlooked their insults.

Thus it was very hard for him after the Raid to find his life long friends throwing him over. He was so cynical over some that it preyed on his mind till the last.

"Two telegrams I always remember taking down and sending off were one to arrest Siqcase, the Pondo chief (before sending it he said it was not constitutional and that the Chief Justice would release him, which he did, and on my asking the reason, he replied "It will save bloodshed," which also happened, and the other one was to Jameson quoting St. Luke, about a king going to war, in connection with the Matabele murders at Victoria.

"Now both these telegrams were sent after two or three hours' most serious thought. He came home on both occasions from sitting in Parliament in the afternoon, and neither was sent until just on closing time at 5 o'clock. Mitchell says he laconically replied to Jameson "Read Luke XIV 31." I mention these two cases because to my mind they were two of the most serious decisions he had to make during his life, and to both of which he gave very serious thought, and no one except myself can record the true facts."

END OF TEXT FROM THE NEWSPAPER CUTTING

Denise found this link on the Wills of Cecil Rhodes and it reads:-

“314 CECIL JOHN RHODES

5. I give an annuity of £100 to each of my servants Norris and the one called Tony during his life free of all duty whatsoever and in addition to any wages due at my death.”

End of quote

On the death of John my Dad, Charles, inherited Devonshire at the expense of giving up the house he had built for my mother, Violet May. This home went to his sister Marjorie as he inherited the farm.

Death Certificate of Mrs. E.R. Norris

Charles was born on Rhodes's Estate on 6 February, 1900. As children we were told that he was the first male white to be born in the Eastern Districts. I cannot prove this

Charles and Violet Norris Wedding in 1933

Charles married Violet May Emery, the daughter of a Railway Train Driver, who was also born in Umtali on 22 May 1912. Yes, you guessed it, they were married in Umtali in 1933. The house mentioned above was his wedding present to Mom and he also gave a .25mm Mauser Pistol which is still in the family.

Another family story was that my Mother's Dad, Frank, drove the first train across the Victoria Falls but I have no proof of this.

Their children, all born on Devonshire Farm were, Charles, John Frank (Jack), Robert Harry (Bob), Violet May (Vi), Edward Leslie (that’s me), Lawrence Ernest (Pookie) and Elizabeth Rose (Nina)

Charles (Dad) was a very active member of the Sons of England (SOE) and I was an active Freemason for many years in South Africa. When I fell ill (in 2002) the Freemasons did not support me or my family and that is the reason why I no longer participate, I do however believe in the principles. Members of the Rhodesian Air Force never once failed in their support and my thanks to them all.

For many years I have been recording the memories of the Rhodesian Air Force and on the Umtali Folk, this has been a labour of love and will hopefully prove that Rhodesians were not the bad folk as many were led to believe by Britain, America and the Communist World.

It has been established that John (Jack) Norris was Killed in Action in Loos, France on May 17, 1916 and aged 22, It is thought he was born in Cape Town. I will endeavour to confirm this.

Grave of John (Jack) Norris in Loos, France

My hope has been to live up to the high standards of the Pioneers of Rhodesia, and my parents Very high standards, but I try.

The two most important days in my life are September 12, our Pioneer Day and November 11, Rhodesia Day, the day Rhodesia went alone and were condemned by the very folk that my Uncle and many Rhodesian gave their lives for in WW 1 and WW 2.

I conclude by saying that I was told in the 1980's that I never qualified to become a member of the Rhodesian Pioneer and Early Settlers Association, I leave it to you to answer that!

I also hope my friends now know why I love Umtali and Rhodesia with a passion.

I thank you for your time

Eddy Norris

Whether resident at Inyanga or not, these pioneering land¬owners were prepared to take active steps to remedy the comparative isolation of their farms, and the building of the road from Umtali was an excellent example of self-help [53]. It was built in the main in 1895 under an arrangement whereby "Government", through the agency of G. Pauling, the Commissioner of Works, undertook to supply labour and materials such as tools and explosives. A committee of landowners was responsible for the raising of funds at three pounds ($6) per 1 500 morgen (about 1 285 ha), and for the implementation of the road work. The work was supervised by Fotheringhame.

In addition, the re-alignment of the transcontinental telegraph took place in those early days [54]. The old line, spanning the country between Salisbury and Mount Darwin, crossed some unhealthy territory. The timber poles had not proved durable; nor had they been treated with marked respect by tribesmen during the days of the rebellion. The new line was routed from Umtali via Inyanga to the Zambesi at Tete, and thence to Nyasaland, with the ultimate object of connecting up with Uganda and Egypt. Arrangements for this project were entrusted by Rhodes to Jameson in 1897, the latter having just returned to Rhodesia depressed both in spirit and in health after a spell of Imprisonment in England for his part in the Jameson Raid [55]. G. H. Tanser records that Jameson set up a store for the project on the site of the present Anglers Rest Hotel [56]. The resilient and adventurous Jameson, after negotiating with the Portuguese for the telegraph route, embarked on an arduous journey by dugout down the Zambesi from Tete to the sea [55].

Inyanga's Van Niekerk is reported to have played a part in the installation of the telegraph offices at Inyanga and at Tete, thereafter proceeding to Blantyre [57].

By April 1898, communication with Blantyre was established [58].

Government officials of the period must also have undertaken some challenging trips, and one imagines that the most knowledgeable of all as regards both the glory of the views and the difficulties of the terrain must have been H. J. Pickett, who surveyed the great majority of the farms and ultimately became an Inyanga landowner himself, when he took over the farm Albany. In his surveys he had to contend not only with mountains and gorges (and one can say with confidence, rain and mist), there was also the sensitive question of the border with Portuguese East Africa to be taken carefully into account. Some 3 500 morgen (3 000 ha) of the Inyanga Block were found to intrude into Portuguese territory [33].

The administration of African affairs, police work, and other services also demanded some challenging and wide-ranging journeys. At first these involved tours of duty from temporary camps and from centres such as Umtali. There is a reference in the records, to a Police station in the region in July, 1898 and Native Department officials operated from hut camps. The first Native Commissioner with responsibility for Inyanga from Umtali headquarters was, nominally at least, E. H. Compton Thomson. However, after a spell of duty of less than three months between September and December, 1894, Compton Thomson was transferred to the Range and it is his successor J. W. Nesbitt (owner of the Inyanga farm Warrendale) who is generally acknowledged as the first Native Commissioner for Inyanga, although stationed at Umtali. After an early visit In his official capacity he sent to Inyanga, as resident Assistant Native Commissioner, J. W. Gray, who was there until 1899. The first substantive Native Commissioner resident in the area was T. B. Hulley, who was transferred there temporarily from Umtali in 1902 and returned to his former station in 1903. By this time the Native Department had moved from the vicinity of Sanyangas Garden. Hulley had built a new hutted camp and his office was a small cottage lent by Weinholt and Michell, managers of Rhodes Estate [60].

Rhodes and Inyanga

Rhodes' interest in Inyanga was inspired by J. G. (later Sir James) McDonald, who became one of his Trustees, and wrote one of the most popular of Rhodes' many biographies.

In 1896, fresh from his historic "indabas" in the Matopos with the rebellious Matabele, but still beset by problems arising from the Jameson Raid and by anxieties arising from the Mashona Rebellion, Rhodes visited Inyanga for the first time61. He gloried in the change of scene, was deeply impressed with the grandeur and promise of the area, and instructed the purchase of up to 100 000 acres (about 40 000 hectares) [62].

He visited Inyanga again in 1897, and because of illness stayed for some time. Jameson, returning from his journey down the Zambesi following the telegraph line negotiations, immediately took over attendance oh him and during the long weeks of recuperation the two men became fully reconciled; a blessing to both after the strain to which their friendship had been Subjected by the Raid and its consequences. Full of schemes for the running of livestock and experiments with a variety of crops, ideas which found expression in the subsequent activities of his managers and in the terms of his will some five years later Rhodes was able, during his recovery, to spend some time in developing his ideas further, and in getting to know the area more intimately by riding over it [63]. Colvin writes of him that he and Jameson explored the country with schoolboy zest [55] and McDonald records that he spent many hours with the local farmers, never grudging the time given to finding a solution to their difficulties [64].

Rhodes' final visit to Inyanga was in 1900 after his frustrating experience in the siege of Kimberley [65]. For the last time, in July and August of that year, he immersed himself in the tranquility of the area he had grown to love.

His early managers at Inyanga were J. Grimmer and J. Norris [66]. For a considerable period they were together on the Estate an arrangement not entirely to the liking of either of them. Like many farmers before and since, they went through some torrid times. A doleful report by Norris to Rhodes in May, 1899, refers to deaths among the livestock, failure of the wheat and oats crops due to bad seed; barley and vegetables swamped by heavy rains; potatoes diseased; fig and pear trees disappointing. Six months

before, the locusts had "eaten everything off". Rhodes' impatience at this time engendered a certain amount of bitterness [52]. Nevertheless they persevered. By 1901, under their direction, an afforestation programme was under way in the orchards about 1 400 fruit trees were doing well and were expected to bear In that year; among the sheep it had been found that Merinos were not thriving but that Cape sheep crossed with Persian rams did better; and of the 400-500 head of cattle which were being ranched, Herefords and Devon’s seemed better suited than Shorthorns, Frieslands' and other stock [68].