The Mazoe Patrol

By Lindsay Fourie

(Photographs by courtesy of the National Archives)

The following story is the main part of a prize-winning project written four years ago, by Lindsay Fourie, while she was still a pupil at Blakiston School in Salisbury. Lindsay, now studying for "O" Levels at Queen Elizabeth School, wrote this project to mark the anniversary of the Mazoe Patrol, which is celebrated by the staff and pupils of Blakiston School every year at this time.

Chapter 1

MY NAME IS Mrs. Salthouse, and the story I'm going to tell you is one of the unbelievable courage of the men in the Mazoe Patrol.

It all started in June, 1896:—

The Mashonas had risen unexpectedly to help their former oppressors, the Matabele. From the 15th to the 18th of June, and many days after, almost every hour brought tragic tidings.

Unsuspecting prospectors, miners and travellers were being attacked and slaughtered from all directions.

Stores and lonely houses were taken after the owners were killed. Refugees were cut off in attempting to come in.

Various outlying communities were besieged, and all the occupants cruelly slaughtered and assegaied.

Judge Vincent, the Chartered Company's acting administrator, could only get 250 men and 80 rifles to protect the 300 women and children in Salisbury. Desperate efforts were being made to divert a column on its way to the front from Natal, but transport difficulties were likely to delay their arrival.

Mr. Dan Judson, chief inspector of the Chartered Company's Telegraphs, was one of the few men who had predicted the Matabele rebellion. He had recently performed the daring feat of riding alone at night through the enemy's camp fires from Gwelo, across country into Mashonaland, and he had observed the armed watchfulness among the Mashonas.

Mr. Judson wired to my husband. Manager of the Goldfields Mazoe Company, the news of the murders as it came in. This was to put him on guard against treachery.

When, early on Wednesday, June 17th, Mr. Judson had occasion to wire us the list of the terrible Norton Massacre, he suggested that we, the three women, had better come into Salisbury, where a strong laager was being constructed. Later that evening the Government received the news that a large Impi, responsible for many massacres including the Norton, was marching on to Mazoe. On hearing this news, Mr. Judson went to Judge Vincent and obtained his permission to take a conveyance to Mazoe, as this was the only way to get

the women into Salisbury quickly. At midnight a wagon and six mules left the telegraph office in charge of Mr. John Blakiston, Mr. Judson's clerk, and Trooper Zimmerman of the Rhodesia Horse. Blakiston, a young man of 27 years, persuaded Mr. Judson to let him take Judson's place. He had pleaded hard for indulgence, saying, "Let me go, Mr. Judson. I have had no excitement since I came to this country; there is sure to be some now. Let me go this once!"

The party at Mazoe consisted of some Cape boys 14 Mashonas, Mr. and Mrs. Dickenson, Messrs Archer-Burton, Spreckley, Fairbairn, Pascoe, Stoddart Fault, Goddard, Darling, my husband, and myself. Except for Mr. Cass, who was a farmer, and Mr. Rout ledge, who was with the Telegraph Department, most of our party were connected with the mines. At 9 a.m. on the 18th June, a telegram arrived from Blakiston, announcing that he had arrived safely and that he was ready to leave with us women after breakfast.

On going to the office, Mr. Judson was astonished, believing Mazoe to have been deserted since morning, to hear the instrument clicking. It ceased as he entered, and Lieutenant Harnson silently handed him this message:

"BLAKISTON TO INSPECTOR JUDSON. THREE MEN KILLED. ALICE MINE SURROUNDED. SEND HELP AT ONCE. OUR ONLY CHANCE. GOODBYE."

Three minutes after the instrument stopped clicking, the heroic signaller of that message was lying dead on the grass.

Just before sunset, the little patrol of one officer and four men rode out of town on its forlorn errand. The party consisted of Judson, and Troopers Honey Guyon, Godfrey Kind, and Hendriks, and three miles out was joined by Captain Stamford-Brown.

The wagonette in which the women and wounded men were brought from the Alice Mine

Five miles out, the patrol met two Salisbury outposts, who reported that they had been ten miles along the road without seeing a sign of anything coming in the distance. This was bad news. The fact that there was no sign of the refugees meant that either they had been slaughtered, or were in laager somewhere and in urgent need of help.

Chapter 2

When it was decided that we Mazoe people should go to Salisbury, a party of men, with fourteen natives and a cart, drawn by two donkeys, to carry provisions, started on ahead. At about 11 o'clock in the morning they left the rough laager which had been constructed the day before. They had not gone three miles when the native carriers led them into an ambush. Messrs. Cass and Dickenson were killed on the grass with assegais and knobkerries, while the rest turned the cart and jumped in. They had not gone far, however, when Faull, who was driving, was shot by a concealed native, and almost at the same moment one donkey was killed, and the other wounded. The surviving men abandoned the cart and ran for their lives.

They met the wagonette containing Mrs. Cass, Mrs. Dickenson, and myself. Shooting for all they were worth at the fifty or so natives who pursued us, the men drove us safely to the shelter of the laager.

And then we realised that a message had to be wired to Salisbury for relief. All of us knew that it was certain death for whoever took the message.

Then Mr. John Blakiston volunteered to take the message if Routledge, who was a telegraph operator,would accompany him to transmit the message. These brave men knew too that they would surely die, yet they were prepared to give their lives to save others.

Mr. Blakiston was wounded in the foot before he reached the telegraph office, but he sent his message and, with it, his goodbye.

We saw Blakiston and Routledge on their return journey, when they were about 1 700 yards away.Blakiston fell in the road, he and his horse riddled with bullets. Routledge ran for refuge in the bush, but we never saw him again.

All through that dreadful day, the rebellious Mashonas, led by the Matabele warriors, fired into the laager. But the men in the laager shot well, and by killing a number of the enemy, prevented them from rushing the laager. When it was dark the rebels did not fire at us, but resumed at dawn. Unfortunately they had crept up to within 150 yards of the laager and, at this close range, fired with tremendous vigour. Our narrow escapes were miraculous, but we were exhausted, and suffered from lack of food and drink. However, at two o'clock the relief arrived, and the enemy practically ceased firing.

Mr. Judson and his patrol were obviously heading for the telegraph office. We all joined in one loud shout, in order to attract their attention. Fortunately they heard us, and turned around. They then shot a pathway for themselves, and, still firing at masses of enemy that surrounded the laager, they galloped up the kopje, and soon we were all united.

But Judson and his patrol also had a long story to tell.

Thomas George Routledge, seated at the instrument in the Transcontinental Telegraph Office, Mazoe, where he sent the message to Salisbury for relief of help, he ordered Trooper King to ride back to Salisbury with a letter to the Commandant, describing the situation.

Chapter 3

When Mr. Judson realised that we had either been slaughtered or were in the laager in urgent need.

The patrol then pushed on and, after one brief halt to loosen girths, and allow men and horses a hasty meal, rode on to Mount Hampden, and again halted, keeping a sharp look-out all the time. Here, at half past three in the morning, they were joined by a reinforcement from Salisbury, consisting of Troopers Finch, Pollett, Niebuhr, Coward, Mulvaney, and King. At a quarter past four the whole party made a start and, after a series of mishaps, reached the Mazoe River. They then proceeded to the farm house, which was found to have been recently deserted. There the men and horses had a two hour rest. This was absolutely necessary due to the fatigue of both. A plentiful supply of food and drink was taken by both men and horses.

The vedettes, posted during the halt as guards, reported that they had seen swarms of natives running about on the distant kopjes in a great state of excitement.

Before starting, Judson addressed his comrades, pointing out that they were about to enter what might prove a death trap. Not a man, however, tried to shrink from the mission.

Descending the rise on which the farm stands, they crossed the Tatagora River,and proceeded in Indian file, Judson leading the patrol.

After covering a mile or more, they entered a stretch of very tall, dense grass, in length about 300 yards, terminating in a perfect jungle. This was obviously an ideal spot from which the natives could fire at the patrol, and Judson realised this. Turning in his saddle, he gave the abrupt order, "Gallop!" Still in single file they tore along. Judson dashed through the worst patch about ten yards ahead of Brown, who was closely followed by the others. Then he wheeled his horse around and, raising his gun, covered the thickest clump of grass, past which Niebuhr and Pollett were then galloping. As they did so, a dozen shots rang out in rapid succession, killing two horses, and injuring Niebuhr severely. Pollett was badly shaken. While the others captured the enemy's attention, Judson got Niebuhr on to his horse. They then started off at a gallop. Before they had gone very far a large party of natives was seen running parallel with them, obviously to cut them off. Judson immediately stopped the party, and fired volley after volley into the enemy, thus forcing them to retreat.

Once more the party started forward, but this time at a gentle canter, emptying their rifles as they rode. On approaching thick clumps of grass, among which many natives were concealed, the party fired into them as they neared the danger spots, and then rushed past at a flying gallop.

About four miles on they saw a wrecked cart with a dead donkey in the traces. A wounded donkey stood a few yards off. Near the cart was the body of a white man, neatly covered with branches. The party found the body to be that of Faull.

At this, the instant thought of all was that Mazoe had been wiped out, and therefore their ride had been in vain. Judson told his comrades that if they did not find their friends alive, they were to ride to the telegraph office somehow, and inform the authorities of their plight. They would then laager as best they could. The fact that they had no food and little ammunition forced them to realise that this would mean certain death.

The fire that was opened on them as they approached the end of the valley was simply terrific, and if they had not returned fire and used good galloping tactics, not a man of them would have lived through it.

Then, just as they were heading for the telegraph office, they heard a great shout behind them. Looking around they saw, waving frantically from a laager on a kopje near Alice Mine — us!

Chapter 4

A Hottentot boy named Hendrik, induced with the promised reward of £100, rode to Salisbury with a despatch asking for a reinforcement of forty men He set off at about 2 a.m. and, I suppose due to the fact that he looked so unlike a courier, he got through the enemy without being touched.

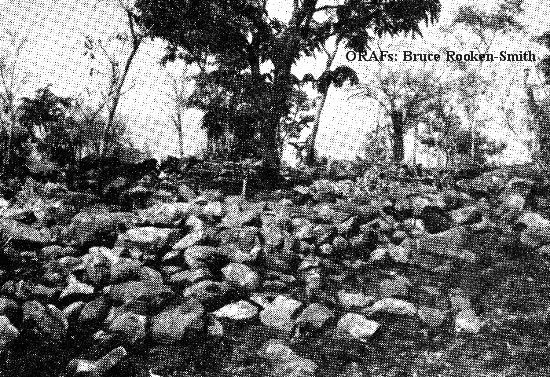

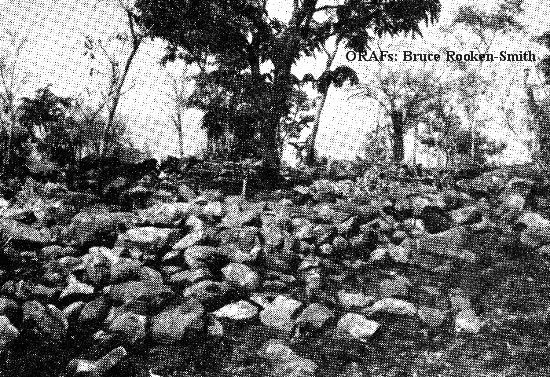

Fort Mazoe (1970), showing the graves of Blakiston and Routledge

In this photograph, Mr. and Mrs. Salthouse are seated on the extreme right and Dan Judson on the left

On the Gwebi Flats he met Inspector Nesbitt, of the Police, and his patrol of twelve men. Troopers Ogilvie, Harbord, McGregor, Byron, Edmonds, Arnott, A. Nesbitt. Berry, Van Staaden, Zimmerman, McGreer and Jacobs.

The Inspector decided not to wait for further reinforcements, but to start off for Mazoe at once and, partly because of the darkness, they reached Mazoe without fighting. The party reached the laager just before dawn on the 20th, and once more we broke the ominous stillness with a great shout of joy. The party now numbered thirty men and three women, including myself; and after the new arrivals had fed and rested their horses, we all set about preparing for departure.

The wagonette was armoured with sheet-iron which, as we observed at the time, fitted so well that it seemed to be made for the purpose. This sheetiron undoubtedly saved the lives of us women and the wounded. The mules had all been shot or lost, so six men were dismounted, and the six troop horses inspanned in their place, though they had never been harnessed before.

Five mounted men went in front, and behind them eight men on foot, and then seven mounted men and eight footmen behind the wagonette. We started off before noon.

The enemy had again opened fire while the wagonette was being fortified, and this was kept up for the first mile or more of the route. But this was nothing compared to the fire that was opened on us when we reached the first donga, near Vesuvius Mine.

At this donga Mr. Pascoe, who was formerly a member of the Salvation Army, climbed to the roof of the wagonette, where he was a good target for the enemy, and remained there to the end, so that he could report as to where the enemy were.

Then Lieutenant McGreer fell, and his horse bolted, but it was pluckily recaptured and ridden by Hendriks. Then two of the patrol had their horses shot under them. Judson and Stamford-Brown ran back to see McGreer, and found him lifeless, with bullets through his head.

Half mad with thirst and weariness, we struggled forward; the men and horses growing weaker all the time. At times many of the men became too exhausted to lift their rifles, and had to hang on to some part of the wagonette until they regained enough strength to carry on.

The continuous hailstorm of bullets made a deafening rattle against the iron plates, denting it as well. But amid the dreadful uproar, we women uttered no sound, and made no movement, besides passing out handful after handful of cartridges to the men.

Next, Troopers van Staaden and Jacobs were killed, the former falling with the side of his head blown away.

Hendriks, in the front, was shot through the jaws and mouth, and was ordered to abandon the convoy and save himself.

Ogilvie was shot and severely injured, and Mr. Burton, receiving a terrible wound through his face, just managed to clamber into the wagonette, and fell bleeding, to our horror.

Then, at the end of that terrible valley, a plan was hit upon. The mounted men rode forward, cheering wildly as if they had seen the relief coming towards them. The cheering was taken up by the rest of us, and we succeeded!

The enemy's firing slackened, and soon stopped altogether; and before we reached the Gwebi River they were not pursuing us at all. Near this river we unharnessed the wounded leader, who had stood by us so gamely when we needed it so badly.

We then started off painfully to cover the remaining seventeen miles. We reached the Salisbury Laager at about ten o'clock. Our journey was over at last. We received an indescribable welcome, it having been reported that we were all killed.

The survivors of the party of fourteen who took refuge at the Alice Mine, and the two relief forces.

Names, reading from the left

Bottom row: Edmonds, Greer, Mrs. Cass, Mrs. Salthouse, Mrs. Dickenson, Judson and Pollett

Standing: R. Nesbitt Arnott A. Nesbitt Harbord, O. Rawson, Ogilvie, Salthouse, Fairbaim, Spreckley, Niebuhr, Darling, Coward, Hendriks, Hendrik (Hottentot driver) and Honey

Top row. Berry, H. Rawson, Pascoe (on roof), and George (African driver)and one Maxim gun.

Eight men had been killed outright, and six wounded. Six mules, two donkeys, and eleven horses were killed, while most of the remaining horses were wounded.

Chapter 5

Inspector Nesbitt was given a Victoria Cross, but he was the only member of the band whose services were recognised by the Government.

But the brave deeds of all the other gallant men will be remembered — how Dan Judson rode miles to rescue us, how John Lionel Blakiston and Thomas George Routledge volunteered to ride to the telegraph office, how John Pascoe sat on the top of the wagonette, and lastly, the courage and endurance of all those men who took part.

The End

Extracted and recompiled by Eddy Norris from the magazine Rhodesian Knowledge Number 2, Winter Issue 1977, which was made available to ORAFs by Bruce Rooken-Smith. Thank you Bruce.

Sincere thanks to Lindsay Fourie for her wonderful story.

Please note that this publication was directed to the youth of Rhodesia.

Comments are always welcome, please send them to Eddy Norris at orafs11@gMail.com

(Photographs by courtesy of the National Archives)

The following story is the main part of a prize-winning project written four years ago, by Lindsay Fourie, while she was still a pupil at Blakiston School in Salisbury. Lindsay, now studying for "O" Levels at Queen Elizabeth School, wrote this project to mark the anniversary of the Mazoe Patrol, which is celebrated by the staff and pupils of Blakiston School every year at this time.

Chapter 1

MY NAME IS Mrs. Salthouse, and the story I'm going to tell you is one of the unbelievable courage of the men in the Mazoe Patrol.

It all started in June, 1896:—

The Mashonas had risen unexpectedly to help their former oppressors, the Matabele. From the 15th to the 18th of June, and many days after, almost every hour brought tragic tidings.

Unsuspecting prospectors, miners and travellers were being attacked and slaughtered from all directions.

Stores and lonely houses were taken after the owners were killed. Refugees were cut off in attempting to come in.

Various outlying communities were besieged, and all the occupants cruelly slaughtered and assegaied.

Judge Vincent, the Chartered Company's acting administrator, could only get 250 men and 80 rifles to protect the 300 women and children in Salisbury. Desperate efforts were being made to divert a column on its way to the front from Natal, but transport difficulties were likely to delay their arrival.

Mr. Dan Judson, chief inspector of the Chartered Company's Telegraphs, was one of the few men who had predicted the Matabele rebellion. He had recently performed the daring feat of riding alone at night through the enemy's camp fires from Gwelo, across country into Mashonaland, and he had observed the armed watchfulness among the Mashonas.

Mr. Judson wired to my husband. Manager of the Goldfields Mazoe Company, the news of the murders as it came in. This was to put him on guard against treachery.

When, early on Wednesday, June 17th, Mr. Judson had occasion to wire us the list of the terrible Norton Massacre, he suggested that we, the three women, had better come into Salisbury, where a strong laager was being constructed. Later that evening the Government received the news that a large Impi, responsible for many massacres including the Norton, was marching on to Mazoe. On hearing this news, Mr. Judson went to Judge Vincent and obtained his permission to take a conveyance to Mazoe, as this was the only way to get

the women into Salisbury quickly. At midnight a wagon and six mules left the telegraph office in charge of Mr. John Blakiston, Mr. Judson's clerk, and Trooper Zimmerman of the Rhodesia Horse. Blakiston, a young man of 27 years, persuaded Mr. Judson to let him take Judson's place. He had pleaded hard for indulgence, saying, "Let me go, Mr. Judson. I have had no excitement since I came to this country; there is sure to be some now. Let me go this once!"

The party at Mazoe consisted of some Cape boys 14 Mashonas, Mr. and Mrs. Dickenson, Messrs Archer-Burton, Spreckley, Fairbairn, Pascoe, Stoddart Fault, Goddard, Darling, my husband, and myself. Except for Mr. Cass, who was a farmer, and Mr. Rout ledge, who was with the Telegraph Department, most of our party were connected with the mines. At 9 a.m. on the 18th June, a telegram arrived from Blakiston, announcing that he had arrived safely and that he was ready to leave with us women after breakfast.

On going to the office, Mr. Judson was astonished, believing Mazoe to have been deserted since morning, to hear the instrument clicking. It ceased as he entered, and Lieutenant Harnson silently handed him this message:

"BLAKISTON TO INSPECTOR JUDSON. THREE MEN KILLED. ALICE MINE SURROUNDED. SEND HELP AT ONCE. OUR ONLY CHANCE. GOODBYE."

Three minutes after the instrument stopped clicking, the heroic signaller of that message was lying dead on the grass.

Just before sunset, the little patrol of one officer and four men rode out of town on its forlorn errand. The party consisted of Judson, and Troopers Honey Guyon, Godfrey Kind, and Hendriks, and three miles out was joined by Captain Stamford-Brown.

The wagonette in which the women and wounded men were brought from the Alice Mine

Five miles out, the patrol met two Salisbury outposts, who reported that they had been ten miles along the road without seeing a sign of anything coming in the distance. This was bad news. The fact that there was no sign of the refugees meant that either they had been slaughtered, or were in laager somewhere and in urgent need of help.

Chapter 2

When it was decided that we Mazoe people should go to Salisbury, a party of men, with fourteen natives and a cart, drawn by two donkeys, to carry provisions, started on ahead. At about 11 o'clock in the morning they left the rough laager which had been constructed the day before. They had not gone three miles when the native carriers led them into an ambush. Messrs. Cass and Dickenson were killed on the grass with assegais and knobkerries, while the rest turned the cart and jumped in. They had not gone far, however, when Faull, who was driving, was shot by a concealed native, and almost at the same moment one donkey was killed, and the other wounded. The surviving men abandoned the cart and ran for their lives.

They met the wagonette containing Mrs. Cass, Mrs. Dickenson, and myself. Shooting for all they were worth at the fifty or so natives who pursued us, the men drove us safely to the shelter of the laager.

And then we realised that a message had to be wired to Salisbury for relief. All of us knew that it was certain death for whoever took the message.

Then Mr. John Blakiston volunteered to take the message if Routledge, who was a telegraph operator,would accompany him to transmit the message. These brave men knew too that they would surely die, yet they were prepared to give their lives to save others.

Mr. Blakiston was wounded in the foot before he reached the telegraph office, but he sent his message and, with it, his goodbye.

We saw Blakiston and Routledge on their return journey, when they were about 1 700 yards away.Blakiston fell in the road, he and his horse riddled with bullets. Routledge ran for refuge in the bush, but we never saw him again.

All through that dreadful day, the rebellious Mashonas, led by the Matabele warriors, fired into the laager. But the men in the laager shot well, and by killing a number of the enemy, prevented them from rushing the laager. When it was dark the rebels did not fire at us, but resumed at dawn. Unfortunately they had crept up to within 150 yards of the laager and, at this close range, fired with tremendous vigour. Our narrow escapes were miraculous, but we were exhausted, and suffered from lack of food and drink. However, at two o'clock the relief arrived, and the enemy practically ceased firing.

Mr. Judson and his patrol were obviously heading for the telegraph office. We all joined in one loud shout, in order to attract their attention. Fortunately they heard us, and turned around. They then shot a pathway for themselves, and, still firing at masses of enemy that surrounded the laager, they galloped up the kopje, and soon we were all united.

But Judson and his patrol also had a long story to tell.

Thomas George Routledge, seated at the instrument in the Transcontinental Telegraph Office, Mazoe, where he sent the message to Salisbury for relief of help, he ordered Trooper King to ride back to Salisbury with a letter to the Commandant, describing the situation.

Chapter 3

When Mr. Judson realised that we had either been slaughtered or were in the laager in urgent need.

The patrol then pushed on and, after one brief halt to loosen girths, and allow men and horses a hasty meal, rode on to Mount Hampden, and again halted, keeping a sharp look-out all the time. Here, at half past three in the morning, they were joined by a reinforcement from Salisbury, consisting of Troopers Finch, Pollett, Niebuhr, Coward, Mulvaney, and King. At a quarter past four the whole party made a start and, after a series of mishaps, reached the Mazoe River. They then proceeded to the farm house, which was found to have been recently deserted. There the men and horses had a two hour rest. This was absolutely necessary due to the fatigue of both. A plentiful supply of food and drink was taken by both men and horses.

The vedettes, posted during the halt as guards, reported that they had seen swarms of natives running about on the distant kopjes in a great state of excitement.

Before starting, Judson addressed his comrades, pointing out that they were about to enter what might prove a death trap. Not a man, however, tried to shrink from the mission.

Descending the rise on which the farm stands, they crossed the Tatagora River,and proceeded in Indian file, Judson leading the patrol.

After covering a mile or more, they entered a stretch of very tall, dense grass, in length about 300 yards, terminating in a perfect jungle. This was obviously an ideal spot from which the natives could fire at the patrol, and Judson realised this. Turning in his saddle, he gave the abrupt order, "Gallop!" Still in single file they tore along. Judson dashed through the worst patch about ten yards ahead of Brown, who was closely followed by the others. Then he wheeled his horse around and, raising his gun, covered the thickest clump of grass, past which Niebuhr and Pollett were then galloping. As they did so, a dozen shots rang out in rapid succession, killing two horses, and injuring Niebuhr severely. Pollett was badly shaken. While the others captured the enemy's attention, Judson got Niebuhr on to his horse. They then started off at a gallop. Before they had gone very far a large party of natives was seen running parallel with them, obviously to cut them off. Judson immediately stopped the party, and fired volley after volley into the enemy, thus forcing them to retreat.

Once more the party started forward, but this time at a gentle canter, emptying their rifles as they rode. On approaching thick clumps of grass, among which many natives were concealed, the party fired into them as they neared the danger spots, and then rushed past at a flying gallop.

About four miles on they saw a wrecked cart with a dead donkey in the traces. A wounded donkey stood a few yards off. Near the cart was the body of a white man, neatly covered with branches. The party found the body to be that of Faull.

At this, the instant thought of all was that Mazoe had been wiped out, and therefore their ride had been in vain. Judson told his comrades that if they did not find their friends alive, they were to ride to the telegraph office somehow, and inform the authorities of their plight. They would then laager as best they could. The fact that they had no food and little ammunition forced them to realise that this would mean certain death.

The fire that was opened on them as they approached the end of the valley was simply terrific, and if they had not returned fire and used good galloping tactics, not a man of them would have lived through it.

Then, just as they were heading for the telegraph office, they heard a great shout behind them. Looking around they saw, waving frantically from a laager on a kopje near Alice Mine — us!

Chapter 4

A Hottentot boy named Hendrik, induced with the promised reward of £100, rode to Salisbury with a despatch asking for a reinforcement of forty men He set off at about 2 a.m. and, I suppose due to the fact that he looked so unlike a courier, he got through the enemy without being touched.

Fort Mazoe (1970), showing the graves of Blakiston and Routledge

In this photograph, Mr. and Mrs. Salthouse are seated on the extreme right and Dan Judson on the left

On the Gwebi Flats he met Inspector Nesbitt, of the Police, and his patrol of twelve men. Troopers Ogilvie, Harbord, McGregor, Byron, Edmonds, Arnott, A. Nesbitt. Berry, Van Staaden, Zimmerman, McGreer and Jacobs.

The Inspector decided not to wait for further reinforcements, but to start off for Mazoe at once and, partly because of the darkness, they reached Mazoe without fighting. The party reached the laager just before dawn on the 20th, and once more we broke the ominous stillness with a great shout of joy. The party now numbered thirty men and three women, including myself; and after the new arrivals had fed and rested their horses, we all set about preparing for departure.

The wagonette was armoured with sheet-iron which, as we observed at the time, fitted so well that it seemed to be made for the purpose. This sheetiron undoubtedly saved the lives of us women and the wounded. The mules had all been shot or lost, so six men were dismounted, and the six troop horses inspanned in their place, though they had never been harnessed before.

Five mounted men went in front, and behind them eight men on foot, and then seven mounted men and eight footmen behind the wagonette. We started off before noon.

The enemy had again opened fire while the wagonette was being fortified, and this was kept up for the first mile or more of the route. But this was nothing compared to the fire that was opened on us when we reached the first donga, near Vesuvius Mine.

At this donga Mr. Pascoe, who was formerly a member of the Salvation Army, climbed to the roof of the wagonette, where he was a good target for the enemy, and remained there to the end, so that he could report as to where the enemy were.

Then Lieutenant McGreer fell, and his horse bolted, but it was pluckily recaptured and ridden by Hendriks. Then two of the patrol had their horses shot under them. Judson and Stamford-Brown ran back to see McGreer, and found him lifeless, with bullets through his head.

Half mad with thirst and weariness, we struggled forward; the men and horses growing weaker all the time. At times many of the men became too exhausted to lift their rifles, and had to hang on to some part of the wagonette until they regained enough strength to carry on.

The continuous hailstorm of bullets made a deafening rattle against the iron plates, denting it as well. But amid the dreadful uproar, we women uttered no sound, and made no movement, besides passing out handful after handful of cartridges to the men.

Next, Troopers van Staaden and Jacobs were killed, the former falling with the side of his head blown away.

Hendriks, in the front, was shot through the jaws and mouth, and was ordered to abandon the convoy and save himself.

Ogilvie was shot and severely injured, and Mr. Burton, receiving a terrible wound through his face, just managed to clamber into the wagonette, and fell bleeding, to our horror.

Then, at the end of that terrible valley, a plan was hit upon. The mounted men rode forward, cheering wildly as if they had seen the relief coming towards them. The cheering was taken up by the rest of us, and we succeeded!

The enemy's firing slackened, and soon stopped altogether; and before we reached the Gwebi River they were not pursuing us at all. Near this river we unharnessed the wounded leader, who had stood by us so gamely when we needed it so badly.

We then started off painfully to cover the remaining seventeen miles. We reached the Salisbury Laager at about ten o'clock. Our journey was over at last. We received an indescribable welcome, it having been reported that we were all killed.

The survivors of the party of fourteen who took refuge at the Alice Mine, and the two relief forces.

Names, reading from the left

Bottom row: Edmonds, Greer, Mrs. Cass, Mrs. Salthouse, Mrs. Dickenson, Judson and Pollett

Standing: R. Nesbitt Arnott A. Nesbitt Harbord, O. Rawson, Ogilvie, Salthouse, Fairbaim, Spreckley, Niebuhr, Darling, Coward, Hendriks, Hendrik (Hottentot driver) and Honey

Top row. Berry, H. Rawson, Pascoe (on roof), and George (African driver)and one Maxim gun.

Eight men had been killed outright, and six wounded. Six mules, two donkeys, and eleven horses were killed, while most of the remaining horses were wounded.

Chapter 5

Inspector Nesbitt was given a Victoria Cross, but he was the only member of the band whose services were recognised by the Government.

But the brave deeds of all the other gallant men will be remembered — how Dan Judson rode miles to rescue us, how John Lionel Blakiston and Thomas George Routledge volunteered to ride to the telegraph office, how John Pascoe sat on the top of the wagonette, and lastly, the courage and endurance of all those men who took part.

The End

Extracted and recompiled by Eddy Norris from the magazine Rhodesian Knowledge Number 2, Winter Issue 1977, which was made available to ORAFs by Bruce Rooken-Smith. Thank you Bruce.

Sincere thanks to Lindsay Fourie for her wonderful story.

Please note that this publication was directed to the youth of Rhodesia.

Comments are always welcome, please send them to Eddy Norris at orafs11@gMail.com

Readers may also like to view the 75th Anniversary of the Mazoe Patrol Brochure by visiting the link below:-

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home