(Development with a national purpose)

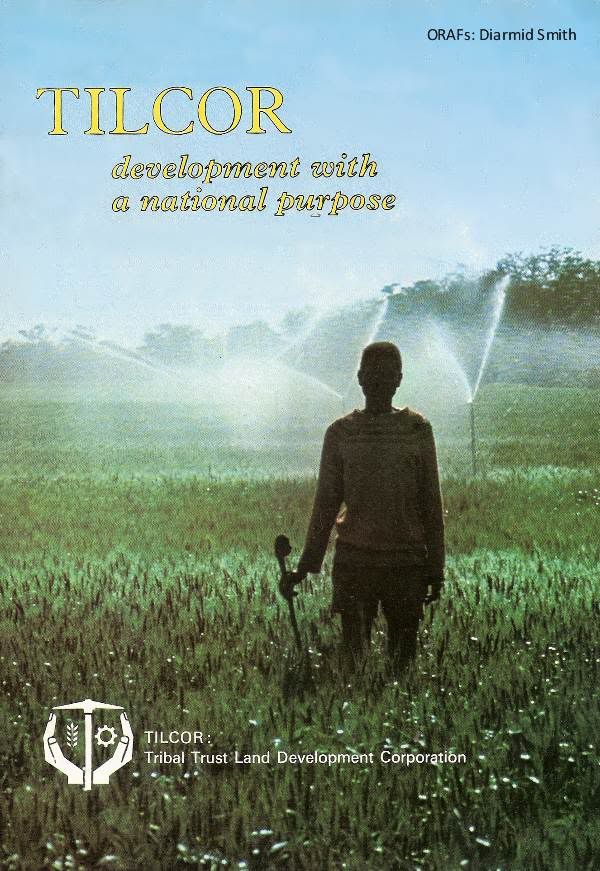

Cover: Irrigation and wheat — new methods and new crops are transforming and improving the life of the traditional tribesman.

Above: The wheat harvest at Chisumbanje, the main winter crop. Cotton is grown in summer. The 41 000 ha of black basalt soil is fertile and holds water well, while the flat nature of the area is ideally suited for large estate management.

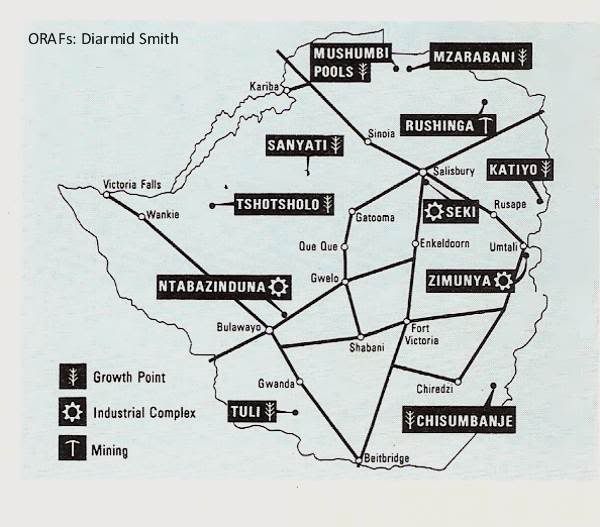

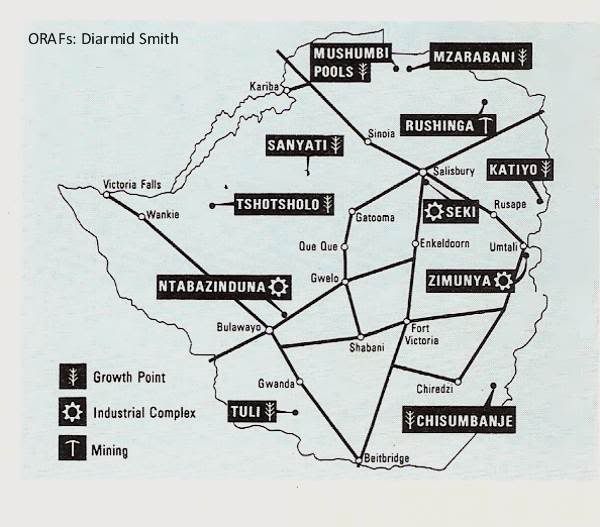

The capital, provided by Government, which has been invested in the creation of growth-points by Tilcor, exceeds R$20 million.

Some of the amounts invested in various areas are:

Seki : R$11.5 million

Chisumbanje: R$8 million

Sanyati: R$I,5 million

Katiyo: R$l,15 million

Tuli: R$300 000

Tshotsholo: R$200 000

All profits from the sale of crops is ploughed back into further group development. Tilcor's ultimate aim is that growth-points, with all= their facilities, will be controlled by the local Africans.

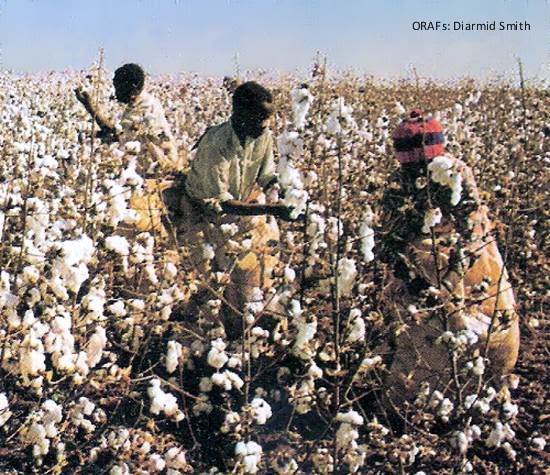

Below: Cotton is a money-maker, both at Chisumbanje and Sanyati. At Sanyati the creation of a central collection and marketing system has encouraged the continued growth of this important crop in the surrounding tribal trust lands. A ginnery for this area is now planned.

In Rhodesia there are 18 million hectares of land reserved for the African, within which a largely traditional way of life continues to exist. By contrast, in the areas dominated by Europeans, due to their more materialistic background and ability to attract and generate capital, development has been rapid and efficient.

The country, therefore, faces an imbalance of development and standards of living — due to the inability of the traditional African areas to organise the capital necessary for growth.

To assist the transition from a subsistence to a cash economy was the essence of the mandate given to Tilcor (Tribal Trust Land Development Corporation) by an Act of Parliament in 1968. In specific terms, to plan, promote, assist and carry out development, in the Tribal Trust Lands, for the benefit of the tribesman.

There are, of course, within tribal areas, a network of Government facilities such as schools, health clinics, and agricultural and community advisory services. But these are barely able to cope with their ever-increasing work — and Government is not entrepreneurial in spirit.

Tilcor's task is to find suitable areas where capital development in an activity in which the rural African can play a full part would lead to a natural development of urban complexes closely related, economically and socially, to the surrounding area.

To establish the magnitude of the task, a survey of all 167 tribal areas of Rhodesia was carried out. During the same period, two large-scale agricultural development projects at Katiyo and Chisumbanje were set in motion.

The three year survey (1969-1972) gave rise to a new policy concept for Tilcor — the Growth Point policy. In simplest terms, this involves the setting-up of profitable development projects in areas remote from existing main centres, whose natural resources can be processed conveniently on site and then transported. Such projects would in turn stimulate general development in the areas. Most important, they would promise increasing employment opportunities for all sectors of the tribal community. Because Tilcor operates on commercial lines, the accent of these growth points is on sustained profitability.

The Eastern Highlands of Rhodesia were already known to be of good tea-producing potential and was the area selected for Tilcor's earliest projects.

From virgin bush in 1969, the Katiyo project, totally undertaken by Tilcor, now has 300 ha under tea. This crop is being processed through a modern tea factory, which when geared to full production will turn out over 1 million kg. of made tea yearly.

New areas being opened up at Katiyo will be supplied from the 2 million cutting nursery of high-yield clonal

Above: The introduction of a cash economy system leads to immediate improvements in living standards, and women particularly are relieved of their traditional labour and acquire modern mother craft and social skills at organised clubs.

Above: Immense capital expenditure in dams, canals, pumping equipment and piping are incurred by Tilcor — to bring water to the land all year round.

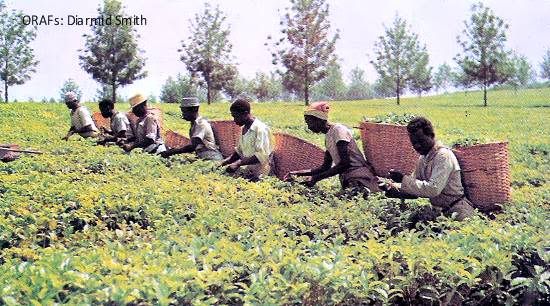

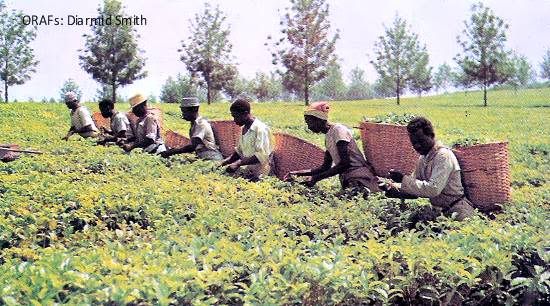

Above: Gathering tea at Katiyo, where the yield has been so encouraging that a processing factory has been installed a year ahead of schedule.

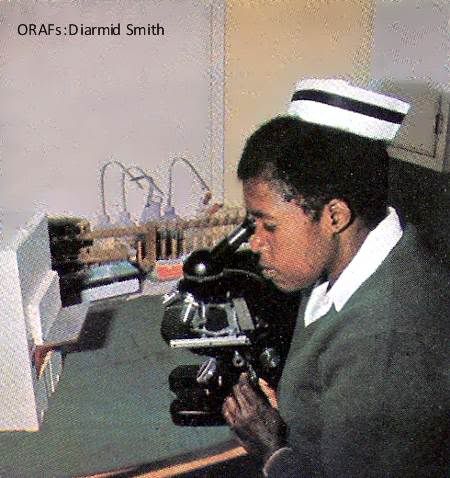

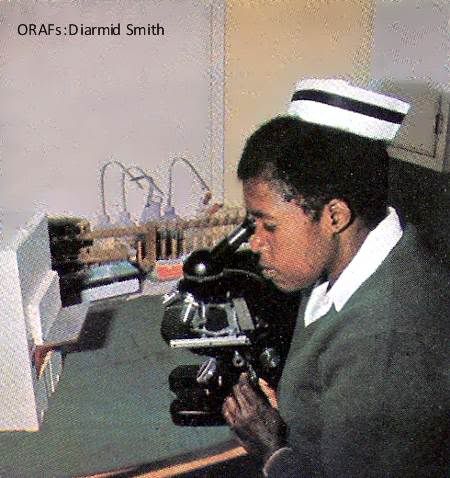

(Above): The creation of rural centres has led to improved health and social services for the previously dispersed tribesmen — a feature envisaged in the Tilcor philosophy, material, the largest of its kind in Southern Africa.

Coffee trees, already planted, warrant the building of a factory to process the crop and the 16 tonnes of coffee beans that it is estimated will be harvested in the first season starting May 1976 will be processed here.

At the opposite end of the Eastern Border from Katiyo is another vast development — Tilcor Chisumbanje Irrigation Estate. The present irrigated area of 2 450 ha of black basalt soil is used to grow cotton in summer and wheat in winter. This is as large an area as can be managed by drawing water from the Sabi River, but the recently completed Ruti Dam will allow a further 10 000 ha to be put to the plough.

Local participation is encouraged in the project. An initial 125 tenant farmers reaped net profits for the 1973-74 season of between $700 and $1 100 each, an extremely satisfactory return when the base rental of $160 plus a cropping cost per hectare has already been deducted from the gross profit. This year the number of tenants has risen to 145.

Local enterprise has already moved into the area with ancillary services such as stores and grinding mills, following the growth-point policy pattern.

The menfolk are not the only ones to benefit from the estate. The women adapt rapidly to their improved financial status and participate eagerly in women's club activities and adult literacy classes.

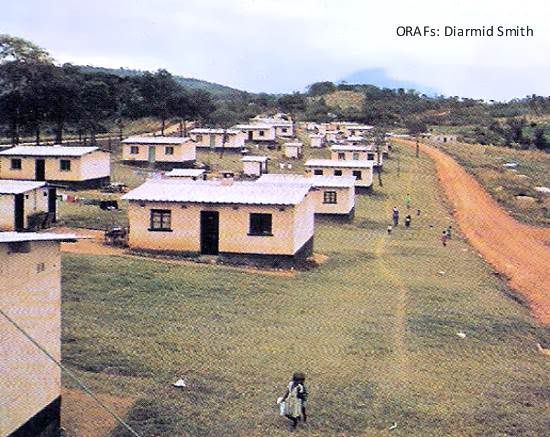

One of the newer projects is the Sanyati Agricultural Scheme. Situated on the banks of the Umniati River, 1 000 ha of old alluvial soils have been cleared, ploughed and planted. This year there are 975 ha of cotton and 101 ha of groundnuts, the balance taken up with trial crops. No development of this size could be complete without housing, and 225 permanent housing units have recently been completed in a fully planned township.

The immediate development planned for Sanyati is a cotton depot now being built in the industrial area of the scheme. A cotton gin in the same area will provide the next development. This would cater for the processing needs of not only the Sanyati area, but also neighbouring proven, high-yield cotton areas — the growth-point concept at work.

Two pilot schemes that envisage crop processing as their major activity have been started in Matabeleland. In the Lupane area is the Tshotsholo scheme. With cotton the main crop on the 100 ha scheme, trials on maize, onions, tomatoes, rice, beans, groundnuts, grapes, citrus and

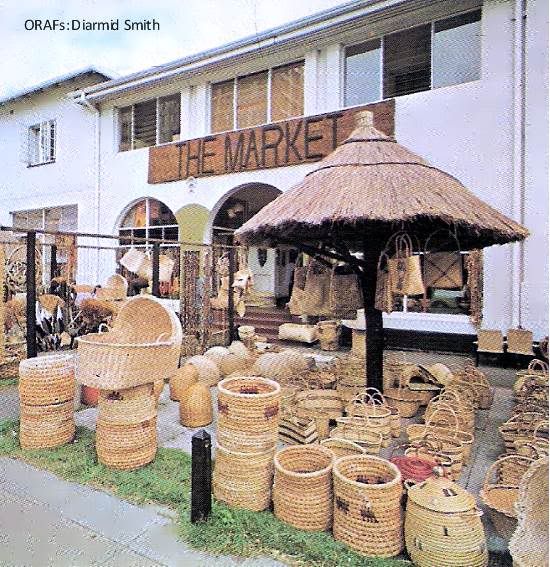

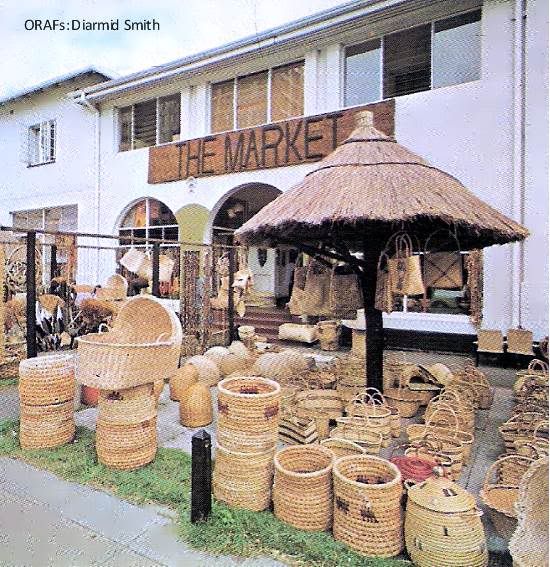

Above: The Market in Salisbury is the focal point for handicrafts produced in remote areas of Rhodesia by tribesmen. Made from natural materials, in traditional fashion, the sale of these goods is often the first step out of a subsistence economy

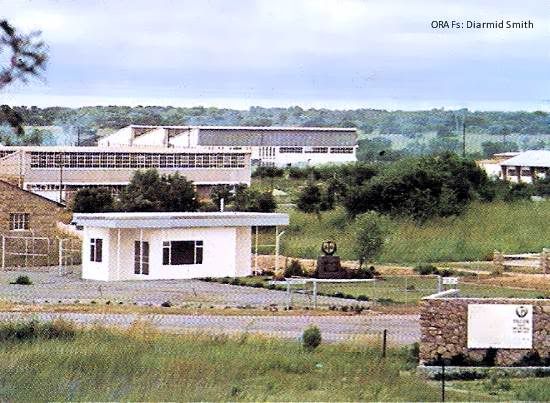

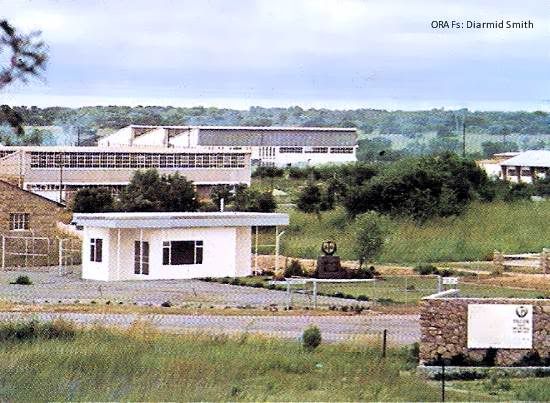

(Below) : Seki Industrial Area, near Salisbury, is the first Tilcor essay into the provision of factories for industrialists in areas where there are large pools of labour. This enables the African to enjoy regular work without deserting his home and family for a distant city.

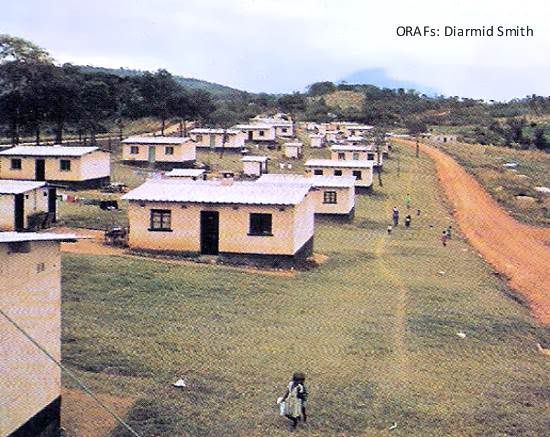

(Above) : The provision of adequate housing, with water and electricity is a key part of Tilcor growth points. The traditional housing may have been more picturesque, but the people who live in these new houses are enthusiastic about the improvement.

Guavas are in progress to establish which can be grown most profitably by tribesmen in the surrounding areas.

Already, very successful dehydration of tomatoes and onions has been carried out at the sister scheme at Tuli in the Gwanda area.

Each project operated by Tilcor has, either on the ground or as part and parcel of its projected planning, proper residential villages with well-built, permanent housing, stores, clinics, beer halls and a full range of sporting and social amenities.

Moving from the agriculturally orientated to industrial schemes, there are three industrial complexes either operational or planned in tribal areas in close proximity to Salisbury, Umtali and Bulawayo. The emphasis of these schemes is that they are actually situated within tribal areas, thereby ensuring a higher rate of cash flow into the surrounding villages.

This also has the effect of stemming the drift of the population to the urban areas, as they now have their town with all its amenities and services in the tribal area.

All this seems to be an impressive list of achievements and plans, but some gaps are obvious. What, one might ask, about the people living in remote, or dry and un-irrigable areas? What about tapping Rhodesia's vast mineral wealth? Both these aspects are being planned for.

In the more remote areas over 2 000 families are engaged in the production of traditional tribal home crafts. Of these, about 800 carry on their activities on a regular basis, using their industry as a main source of income. The remaining 1 200 only use their craft as supplementary income. Items produced find a ready local and tourist acceptance and sale at "The Market", a Tilcor subsidiary outlet for crafts, in Salisbury.

From the beginning of recorded history in Rhodesia, the African people have been known as miners of metals and minerals, and this is being further encouraged and developed in areas where agricultural potential is low.

Time and people do not stand still and this is the focal point of all Tilcor's operations. Future profitable schemes will be of greater value to all sectors of the African population and ultimately to the Rhodesian national economy as a whole.

Tea is a refreshing drink to most people — but a new way of life at KATIYO

(Above): Pickers pluck only the two leaves and a bud at the end of every twig. It is hard work, but it enables the young men to earn a wage without leaving their homes.

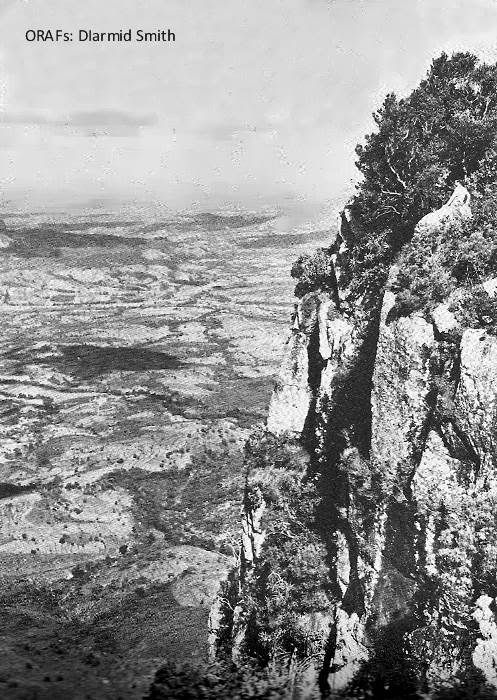

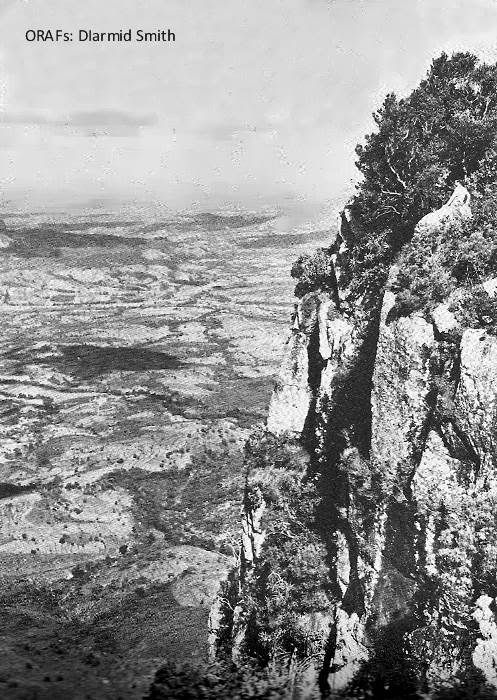

(Below): A tourist's view of the broad Honde Valley from the Inyanga escarpment. There are numerous viewpoints within 30 km of this holiday area's hotels and cottages.

NESTLED at the foot of Rhodesia's highest mountain range, at Inyanga, is a valley of incredible beauty. Lush, fertile plains sweep upwards, in a living canvas of colour, to meet the forbidding grandeur of majestic peaks.

Dropping steeply from the Inyanga escarpment to an altitude of only 700 metres above sea level, the Honde Valley, in the Holdenby Tribal Trust Land, runs eastwards to the Mocambique border. Its fertile abundance comes from the waters of the Honde, Pungwe, Nyakombe and Ruwere rivers.

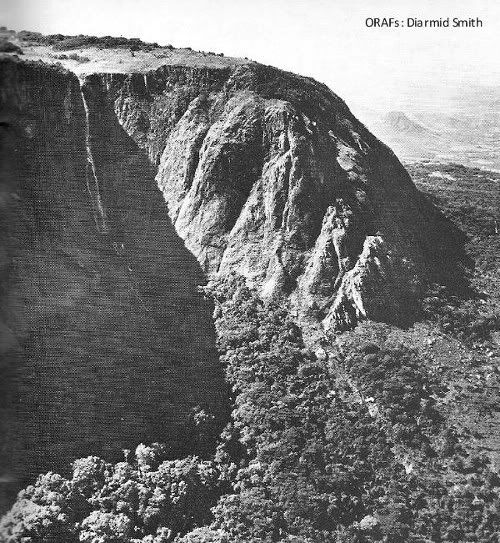

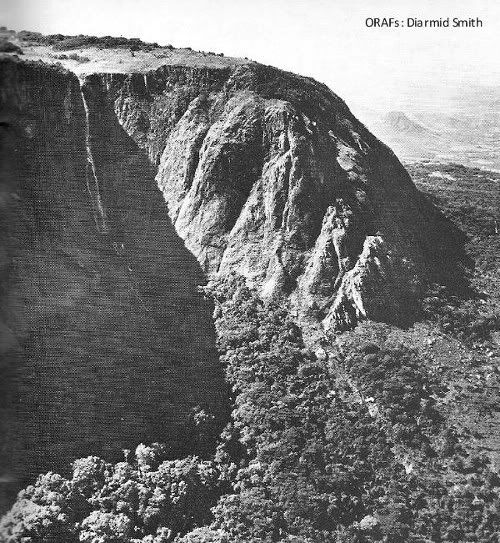

(Above) : The Mtarazi Falls, claimed to be the second highest falls in the world, hurtle over the edge of the Inyanga Escarpment into the thickly wooded slopes below. These dense woodlands are the haunt of the rare blue duiker.

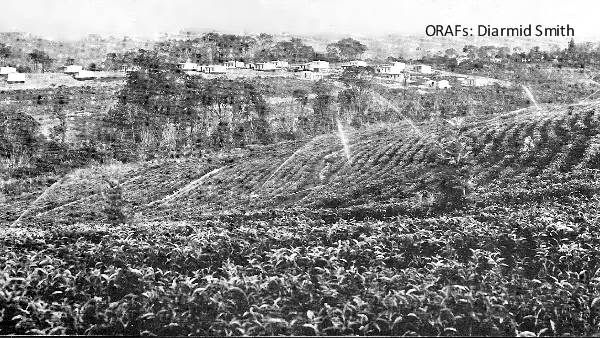

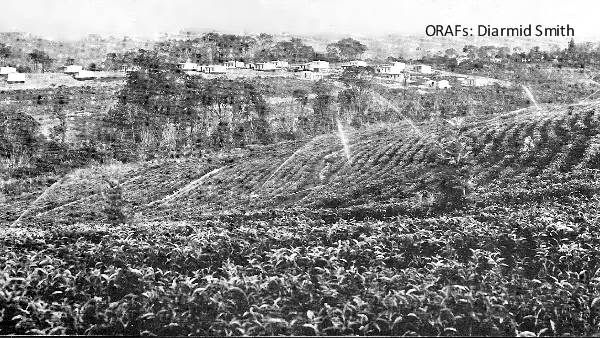

(Below) : Even in the high-rainfall Honde Valley irrigation is needed in the dry season to keep the tea in perfect condition. Beyond this section of the estate are some of the new houses for workers.

It is the home of immense specimens of the African Mahogany tree (.Khaya nyasica), one of which is referred to as the "Big Tree" as it stands some 55 metres tall. It is the setting for the Mtarazi Falls, second highest in the world, which come tumbling 500 metres down to the valley floor.

The tribal population of the valley has never been large, the majority being of Shona extraction. There are a few Ndebele, descendents of Lobengula's impis who, when they failed to carry out his orders in the area, decided to settle rather than return to Matabeleland and face the royal wrath!

One of the biggest problems which faced this underdeveloped area, was the steady exodus of young people to the larger centres of the country.

To counteract this and, at the same time, develop its massive agricultural potential, an investigation was launched, in early 1969, into the possibilities of growing tea. As a result, the Ministry of Internal Affairs, which had for some six or seven years operated a plot-holder

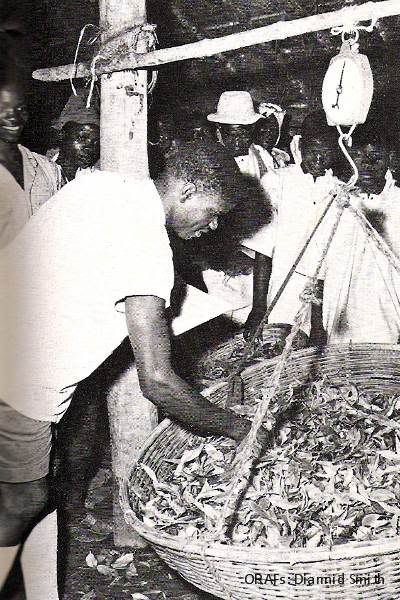

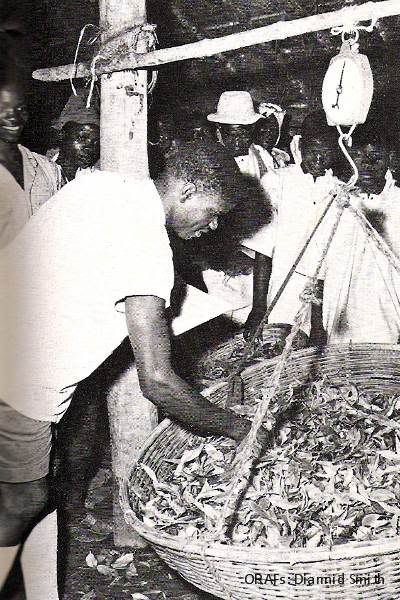

(Above) The pickers bring their work for Weighing in, while the overseer checks the contents of the baskets to ensure that only "two leaves and a bud" have been included. On this depends the quality of the future processed tea.

End

tea scheme in the region, authorised the African Development Fund to invest up to $20 000 on seedlings and establishing seed beds.

Shortly after, Tilcor took over the operation with the object of growing tea profitably under irrigation, using vegetatively propagated planting materials, on an estate-managed basis. In addition, by establishing tea factories, processing plants and ancillary installations, it was felt that local tribesmen could be converted from subsistence to a cash economy

level.

Thus Katiyo Tea Estate was launched — incidentally the word Katiyo means literally "newly hatched chick". Access roads were built through the valley, a nursery established, tea lands surveyed, cut and cleared, and an efficient over- head irrigation system installed. In all, R$I,15 million has been invested. To the layman, tea is merely a pleasant tasting beverage, enjoyed by preference with or without the addition of milk, sugar or lemon, and drunk with or without ceremony.

To the expert, however, the tea bush is a thing of beauty and much of its cycle and growth pattern is still not fully understood. Basically, the bush is planted, watered and, if it survives, achieves its first "flush" of pluck able shoots any time within 6 to 18 months of planting out, and reaches maximum production during its ninth year of growth.

As Katiyo was established on a sound technical footing, the end of the 1972-73 season saw 95 hectares of land producing green leaf. By the middle of the 1976-77 season, no less than 300 hectares of land will be returning green leaf of high quality.

As the main area of profitability in tea production is in the processing — where very reasonable returns per kg of tea can be realised — a R$140 000 tea factory, on the estate, was planned for 1976. However, the production of tea surpassed all expectation and therefore plans had to be advanced by a full year. The factory began production in February, 1975, and by the end of July, 110 000 kg of made tea had been produced. The 1976 production estimate of made tea is 330 000 kg.

Development has advanced in other directions and, at present, there are 20 hectares of land planted to Arabica coffee. The first yield is due in May this year and is estimated at being about seven tonnes. Again, with the primary development of coffee, the allied secondary development of a coffee pulpery and processing facilities on the estate will be ready by the time the crop is harvested.

In the next year or so, the coffee lands will be expanded to cover 88 hectares, which should provide an ultimate yield of at least 32 tonnes a year.

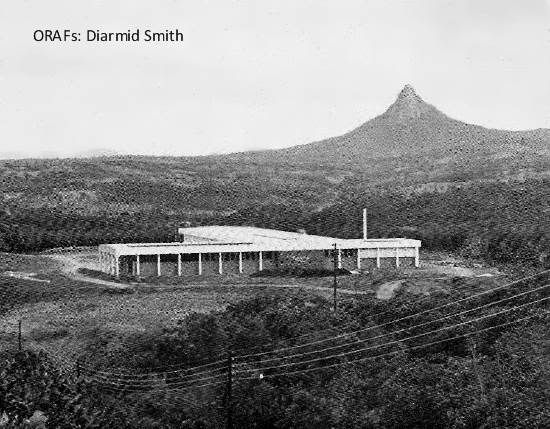

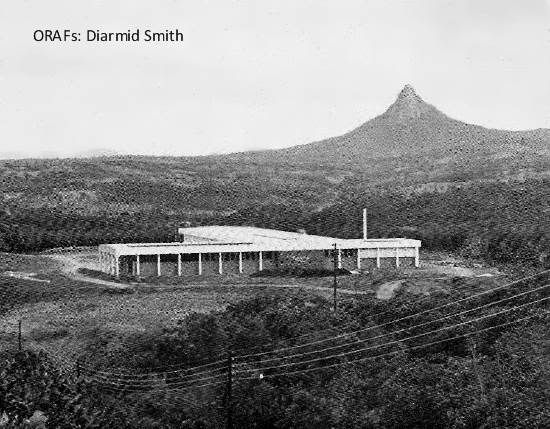

(Above): The new tea-processing factory at Katiyo, which is the first industrial development in the Holdenby Tribal Trust Land. Beyond stretches the fertile valley Which has yet to be developed, opening up a new way of life for the tribesmen.

With electricity and roads already developed for the Katiyo tea estate further development should follow swiftly. Already coffee plantations are ready to bear, and experimental crops are being planted to ascertain the area's suitability for intensive agriculture.

ENd of Caption

The real benefit of Katiyo however, is in the job opportunities creatcd in all sectors. Once both tea and coffee production arc in full swing, the scene will be set to encouragc the move of industry and ancillary services into the area.

End of Article

Above: Immense capital expenditure in dams, canals, pumping equipment and piping are incurred by Tilcor — to bring water to the land all year round.

Above: Gathering tea at Katiyo, where the yield has been so encouraging that a processing factory has been installed a year ahead of schedule.

(Above): The creation of rural centres has led to improved health and social services for the previously dispersed tribesmen — a feature envisaged in the Tilcor philosophy, material, the largest of its kind in Southern Africa.

Coffee trees, already planted, warrant the building of a factory to process the crop and the 16 tonnes of coffee beans that it is estimated will be harvested in the first season starting May 1976 will be processed here.

At the opposite end of the Eastern Border from Katiyo is another vast development — Tilcor Chisumbanje Irrigation Estate. The present irrigated area of 2 450 ha of black basalt soil is used to grow cotton in summer and wheat in winter. This is as large an area as can be managed by drawing water from the Sabi River, but the recently completed Ruti Dam will allow a further 10 000 ha to be put to the plough.

The permanent labour force on the project now stands at 750, but during cotton-picking ten times this number are employed as casual labour.

Local participation is encouraged in the project. An initial 125 tenant farmers reaped net profits for the 1973-74 season of between $700 and $1 100 each, an extremely satisfactory return when the base rental of $160 plus a cropping cost per hectare has already been deducted from the gross profit. This year the number of tenants has risen to 145.

Local enterprise has already moved into the area with ancillary services such as stores and grinding mills, following the growth-point policy pattern.

The menfolk are not the only ones to benefit from the estate. The women adapt rapidly to their improved financial status and participate eagerly in women's club activities and adult literacy classes.

One of the newer projects is the Sanyati Agricultural Scheme. Situated on the banks of the Umniati River, 1 000 ha of old alluvial soils have been cleared, ploughed and planted. This year there are 975 ha of cotton and 101 ha of groundnuts, the balance taken up with trial crops. No development of this size could be complete without housing, and 225 permanent housing units have recently been completed in a fully planned township.

The immediate development planned for Sanyati is a cotton depot now being built in the industrial area of the scheme. A cotton gin in the same area will provide the next development. This would cater for the processing needs of not only the Sanyati area, but also neighbouring proven, high-yield cotton areas — the growth-point concept at work.

Two pilot schemes that envisage crop processing as their major activity have been started in Matabeleland. In the Lupane area is the Tshotsholo scheme. With cotton the main crop on the 100 ha scheme, trials on maize, onions, tomatoes, rice, beans, groundnuts, grapes, citrus and

Above: The Market in Salisbury is the focal point for handicrafts produced in remote areas of Rhodesia by tribesmen. Made from natural materials, in traditional fashion, the sale of these goods is often the first step out of a subsistence economy

(Below) : Seki Industrial Area, near Salisbury, is the first Tilcor essay into the provision of factories for industrialists in areas where there are large pools of labour. This enables the African to enjoy regular work without deserting his home and family for a distant city.

(Above) : The provision of adequate housing, with water and electricity is a key part of Tilcor growth points. The traditional housing may have been more picturesque, but the people who live in these new houses are enthusiastic about the improvement.

Guavas are in progress to establish which can be grown most profitably by tribesmen in the surrounding areas.

Already, very successful dehydration of tomatoes and onions has been carried out at the sister scheme at Tuli in the Gwanda area.

Each project operated by Tilcor has, either on the ground or as part and parcel of its projected planning, proper residential villages with well-built, permanent housing, stores, clinics, beer halls and a full range of sporting and social amenities.

Moving from the agriculturally orientated to industrial schemes, there are three industrial complexes either operational or planned in tribal areas in close proximity to Salisbury, Umtali and Bulawayo. The emphasis of these schemes is that they are actually situated within tribal areas, thereby ensuring a higher rate of cash flow into the surrounding villages.

This also has the effect of stemming the drift of the population to the urban areas, as they now have their town with all its amenities and services in the tribal area.

All this seems to be an impressive list of achievements and plans, but some gaps are obvious. What, one might ask, about the people living in remote, or dry and un-irrigable areas? What about tapping Rhodesia's vast mineral wealth? Both these aspects are being planned for.

In the more remote areas over 2 000 families are engaged in the production of traditional tribal home crafts. Of these, about 800 carry on their activities on a regular basis, using their industry as a main source of income. The remaining 1 200 only use their craft as supplementary income. Items produced find a ready local and tourist acceptance and sale at "The Market", a Tilcor subsidiary outlet for crafts, in Salisbury.

From the beginning of recorded history in Rhodesia, the African people have been known as miners of metals and minerals, and this is being further encouraged and developed in areas where agricultural potential is low.

In the extreme north of Rhodesia, in the hot, dry, Zambezi Valley, are Tilcor's most recent ventures. At Mushumbi Pools Estate, given Government approval in June, 1975, already 200 ha of wild bush has been cleared and planted to cotton. Plans for this estate envisage 1 000 ha under cultivation and seasonal employment for 3 000 tribesmen. This is in an area where, until Tilcor moved in, there was not even a reasonable road. Nearby at Mzarabani a sister estate and growth point is to be established.

Time and people do not stand still and this is the focal point of all Tilcor's operations. Future profitable schemes will be of greater value to all sectors of the African population and ultimately to the Rhodesian national economy as a whole.

Tea is a refreshing drink to most people — but a new way of life at KATIYO

(Above): Pickers pluck only the two leaves and a bud at the end of every twig. It is hard work, but it enables the young men to earn a wage without leaving their homes.

(Below): A tourist's view of the broad Honde Valley from the Inyanga escarpment. There are numerous viewpoints within 30 km of this holiday area's hotels and cottages.

NESTLED at the foot of Rhodesia's highest mountain range, at Inyanga, is a valley of incredible beauty. Lush, fertile plains sweep upwards, in a living canvas of colour, to meet the forbidding grandeur of majestic peaks.

Dropping steeply from the Inyanga escarpment to an altitude of only 700 metres above sea level, the Honde Valley, in the Holdenby Tribal Trust Land, runs eastwards to the Mocambique border. Its fertile abundance comes from the waters of the Honde, Pungwe, Nyakombe and Ruwere rivers.

(Above) : The Mtarazi Falls, claimed to be the second highest falls in the world, hurtle over the edge of the Inyanga Escarpment into the thickly wooded slopes below. These dense woodlands are the haunt of the rare blue duiker.

(Below) : Even in the high-rainfall Honde Valley irrigation is needed in the dry season to keep the tea in perfect condition. Beyond this section of the estate are some of the new houses for workers.

It is the home of immense specimens of the African Mahogany tree (.Khaya nyasica), one of which is referred to as the "Big Tree" as it stands some 55 metres tall. It is the setting for the Mtarazi Falls, second highest in the world, which come tumbling 500 metres down to the valley floor.

The tribal population of the valley has never been large, the majority being of Shona extraction. There are a few Ndebele, descendents of Lobengula's impis who, when they failed to carry out his orders in the area, decided to settle rather than return to Matabeleland and face the royal wrath!

One of the biggest problems which faced this underdeveloped area, was the steady exodus of young people to the larger centres of the country.

To counteract this and, at the same time, develop its massive agricultural potential, an investigation was launched, in early 1969, into the possibilities of growing tea. As a result, the Ministry of Internal Affairs, which had for some six or seven years operated a plot-holder

(Above) The pickers bring their work for Weighing in, while the overseer checks the contents of the baskets to ensure that only "two leaves and a bud" have been included. On this depends the quality of the future processed tea.

End

tea scheme in the region, authorised the African Development Fund to invest up to $20 000 on seedlings and establishing seed beds.

Shortly after, Tilcor took over the operation with the object of growing tea profitably under irrigation, using vegetatively propagated planting materials, on an estate-managed basis. In addition, by establishing tea factories, processing plants and ancillary installations, it was felt that local tribesmen could be converted from subsistence to a cash economy

level.

Thus Katiyo Tea Estate was launched — incidentally the word Katiyo means literally "newly hatched chick". Access roads were built through the valley, a nursery established, tea lands surveyed, cut and cleared, and an efficient over- head irrigation system installed. In all, R$I,15 million has been invested. To the layman, tea is merely a pleasant tasting beverage, enjoyed by preference with or without the addition of milk, sugar or lemon, and drunk with or without ceremony.

To the expert, however, the tea bush is a thing of beauty and much of its cycle and growth pattern is still not fully understood. Basically, the bush is planted, watered and, if it survives, achieves its first "flush" of pluck able shoots any time within 6 to 18 months of planting out, and reaches maximum production during its ninth year of growth.

As Katiyo was established on a sound technical footing, the end of the 1972-73 season saw 95 hectares of land producing green leaf. By the middle of the 1976-77 season, no less than 300 hectares of land will be returning green leaf of high quality.

As the main area of profitability in tea production is in the processing — where very reasonable returns per kg of tea can be realised — a R$140 000 tea factory, on the estate, was planned for 1976. However, the production of tea surpassed all expectation and therefore plans had to be advanced by a full year. The factory began production in February, 1975, and by the end of July, 110 000 kg of made tea had been produced. The 1976 production estimate of made tea is 330 000 kg.

Development has advanced in other directions and, at present, there are 20 hectares of land planted to Arabica coffee. The first yield is due in May this year and is estimated at being about seven tonnes. Again, with the primary development of coffee, the allied secondary development of a coffee pulpery and processing facilities on the estate will be ready by the time the crop is harvested.

In the next year or so, the coffee lands will be expanded to cover 88 hectares, which should provide an ultimate yield of at least 32 tonnes a year.

(Above): The new tea-processing factory at Katiyo, which is the first industrial development in the Holdenby Tribal Trust Land. Beyond stretches the fertile valley Which has yet to be developed, opening up a new way of life for the tribesmen.

With electricity and roads already developed for the Katiyo tea estate further development should follow swiftly. Already coffee plantations are ready to bear, and experimental crops are being planted to ascertain the area's suitability for intensive agriculture.

ENd of Caption

The real benefit of Katiyo however, is in the job opportunities creatcd in all sectors. Once both tea and coffee production arc in full swing, the scene will be set to encouragc the move of industry and ancillary services into the area.

End of Article

Extracted and recompiled, by Eddy Norris, from a publication which was made available to ORAFs by Diarmid Smith . Thank you Diarmid.

Tilcor article was a supplement to the magazine Rhodesia Calls March – April 1976, it was included in the magazine. So presume the publisher would be Rhodesia Calls

The recompilation was done for no or intended financial gain but rather to record the memories of Rhodesia.

Tilcor article was a supplement to the magazine Rhodesia Calls March – April 1976, it was included in the magazine. So presume the publisher would be Rhodesia Calls

The recompilation was done for no or intended financial gain but rather to record the memories of Rhodesia.

Thanks to

Paul Norris for the ISP sponsorship.

Paul Mroz for the image hosting sponsorship.

Robb Ellis for his assistance.

Should you wish to contact Eddy Norris please mail me on orafs11@gmail.com

I spent a few years at Chisumbanje studying the local rat population that feed on winter wheat.Also served for a time with the local PR.Enjoyed the combined MidSabi/Chisumbanje PR patrols,especially at Birchenough Bridge.The winter summers were very pleasant.All in all,an interesting and worth while experience for a liberal Canadian in those interesting and difficult times.

ReplyDeleteIan Hume Writes:-

ReplyDeleteMany thanks for this. I feel bound to comment since I had much to do with and was a strong admirer of Tilcor's concept, execution and accomplishments. In the period 1975-78, invited by three major Rhodesian corporations (the Shell Company; Delta Breweries; and TA Holdings) I took time out from my World Bank career to establish and operate the Whitsun Foundation. This was a small but highly focused outfit, funded by the corporations, whose aim was to prepare plans and projects for the development of the country (mainly rural development and marginal urban areas)of a kind that could be funded by the World Bank and other donors after UN sanctions were lifted (i.e. once Rhodesia becaMe Zimbabwe). We had some success, but not much, mainly because our works (including a land reform concept) were viewed with suspiscion by ZANU-PF and their supporters. Tilcor, a highly successful story also suffered, I believe, from the same suspiscion and was unfairly labelled as a paternalistic offshoot of the much maligned Department of Native Affairs. Does it still exist? Has anything been put in its place as a better model?

Nick Baalbergen (Intaf) Writes:-

ReplyDeleteYes, this is probably a part of our development history that is not widely known.

TILCOR was conceived and implemented by Government in pursuit of its policy to create 'development nodes' in the vast Tribal Trust Land areas of the country. The objective of these development nodes, was that they would form the catalyst for further development, which would become self-sustaining centres of economic activity, creating both jobs and wealth in the Tribal areas. Most of these development nodes were agricultural in nature, the exception being 'Seki' which was an industrial node located near the capital.

As with all infrastructure development, TILCOR was funded by the Government from our very modest taxpayer base, bearing in mind that with the advent of sanctions in the 1960's, all external funding dried up. I would guess that individual taxpayers never exceeded 200 thousand individuals (of course company and mining taxes added to the tax base). Nonetheless, the achievements of TILCOR operating on a shoestring budget, were noteworthy.

The output from the various TILCOR projects (wheat, cotton, tea etc) fed directly into the mainstream economy and therefore contributed to the development of the country as a whole. Sadly, the activities of the various TILCOR projects were hampered and restricted by the intensification of the war.

The development of the Chisumbanje Irrigation Scheme (Chipinga District), is historically linked to the Sabi Experimental Station, located a couple of kilometres to the north. The Sabi Experimental Station, was an agricultural research facility which developed many of the crop hybrids specifically for the area, it was already operational in the early 1950's.

In addition to the various 'high profile' TILCOR projects, there were numerous very successful irrigation schemes developed in the tribal areas. One such scheme that readily comes to mind, is the Nyamaropa Irrigation Scheme, located in the remote Inyanga North lowveld area, on the Gairezi River border with Mozambique. The irrigation manager, Pat Horsfield, was awarded an MSM for continuing to run an exceptionally successful irrigation scheme under increasingly difficult and dangerous conditions. Nyamaropa was particularly vulnerable as the war intensified, due to its location on the border with Mozambique. It was regularly subjected to attacks of various types, from across the Gairezi River.

Myself Tim Jarvis , Donald Teron, John Potgieter and Tony Miller spent a lot of time at Katiyo,doing Electrical work and Power lines construction,whilst we worked for Stan Muller at Mobile Electrical Engineers

ReplyDeleteHi

ReplyDeletePlease if anyone can help me get in touch with Mr Hume regarding that would be greatly apreciated.

I would like to share some information with him on some of these TILCOR,now ARDA estates.

My emails are kuvimbaharvest@gmail.com and danburgz@gmail.com.

Alternatively anyone that can assist with background on these Estates as well as interested investors can contact me. I have been awarded some of the land by government on development contracts.

I am immensely proud of the many achievements of TILCOR as the Chairman, Warwick Bailey was my father in law. They did all sorts of fascinating things such as finding a plant in the Lowveld that produced a lemon essence extract. They also investigated ant heaps for traces of gold the ants had brought up. There was also a clothing factory - I had a tracksuit from there.

ReplyDeleteIt is indeed a tragedy that Mugabe was so virulently against anything started by White Rhodesians and in fact it has been his fanatic racism that has seen the destruction of my country

Yes, VERY proud to "be a Rhodesian". What a pity that Mugabe's virulent Zanu racism did not see the full fruition of the TILCOR project. I visited many of the projects with Warwick Bailey and was deeply impressed.

ReplyDeleteHere was a genuine and successful attempt to lift the Rural People out of poverty and into the prosperity of a cash economy - but was deliberately ignored by our many detractors. As stated, the plan was for local Africans to take over management of the many schemes as they became familiar with the process. From the start, local Chiefs were a part of the Board of Directors of these schemes.

What a huge opportunity lost - through politics!