MAY 1995

Personal Recollections of the History of the Southern Rhodesian Auxiliary Air Force

By D M Barbour done at the request of Peter Cooke A.F.A. Box A.86P.O. Avondale

(By memory, only aide memoire his log book entries)

Note (R) = Regular

Having got my R.A.F. wings on the last course to pass out during World War Two from RATG Cranborne and having subsequently been a member of the Oxford University Air Squadron RAF-VR for two years I returned to Southern Rhodesia at the end of 1948. The RAF were still operating at one station of the War Time RATG Group namely Thornhill and wishing to continue my volunteer commitment I set about trying to find a way to do an annual attachment at Thorn- hill. I don't remember exactly how it happened, but as a result of these efforts I came into contact with the Southern Rhodesian Air Force (I think it had recently been formed from the Southern Rhodesian Communications Wing??).

Somehow or another I was taken on by the SRAF to be kept warm and to be one of the most junior members of the to be formed No.1 Auxiliary Squadron S.R.A.A.F.

Anyhow my log book confirms that on July 18th 1949 I had my first trip in Tiger Moth SR26 with Major Keith Taute (R) described as familiarisation. After about eight hours on the Tiger Moth on August 10th again with Major Taute as my instructor, I moved on to the Harvards. From the flight summary for July, August and September I note that it was headed Southern Rhodesian Auxiliary Air Force and the unit as ELEMENTARY SRAAF and my rank as Rifleman -- but nonetheless special as I was the only guy in the Auxiliary at that stage.

Whilst flying with the Elem SRAAF I note that on the 15th September I participated in the Battle of Britain formation of Harvards (if my memory serves me right every available pilot was involved) -- In October 1949 I had a progress check with Lt Archie Wilson (R) -- That on the weekend of the 5th and 6th of November I went to Zomba and return as 2nd pilot in an Anson Captained by Lt Col Maurice Barber (Director Civil Aviation) -- In the same month I did a dual low level cross country exercise with Captain Harry Hawkins (R) -- In January 1950 I had a dual check ride in a Harvard with Warrant Officer Charles Paxton (R) as my instructor --On January 20th 1950 I was introduced to Battle formation by Lt Neville Brooks (an Auxiliary Officer designated to be one of the Flight Commanders of the soon to be formed No.1 Squadron SRAAF) -- Again if my memory serves me right Major Hardwicke Holderness the to be CO of No.1 Squadron and his deputy Captain John Deall (both Auxiliary Officers) had started flying with the Southern Rhodesian Air Force a few months previously -- end of January early March saw Harry Hawkins introduce me to the Auster and four hours 30 minutes was spent trying to master the little beast.

I am not sure when the Auxiliary Squadron was actually formed but my log book shows that my flying was designated Elem SRAAF until the middle of March 1950 and my first flight with No.1 Squadron was on March 14th 1950.

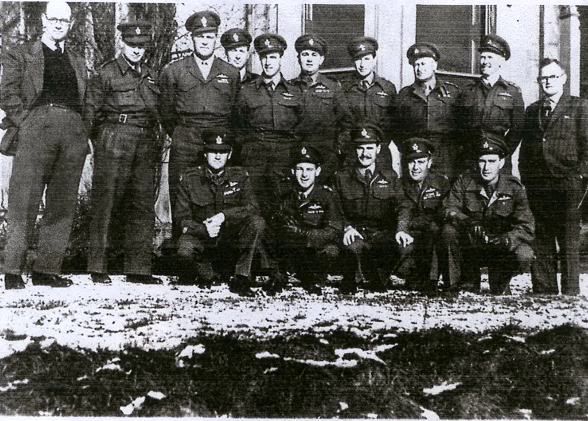

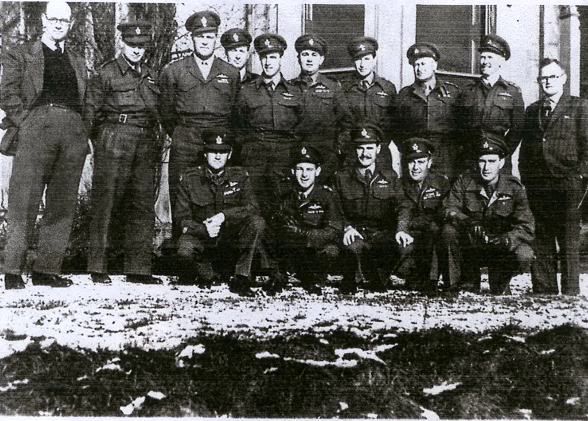

The Squadron Photo attached dated 1950 and taken in front of a Harvard includes I believe the full complement of the founder members listed, below:-

Back Row (Left to Right) Lt D J Richards, Lt D F Bellingan, Lt J C K Campbell, Lt J A Konschel, Lt D M Whyte (R) (Adjutant), Lt D M Barbour, Lt B T A Hone, Lt 0 D Penton

Front Row (Left to Right) Lt D A Bradshaw, Lt A J Douglas, Capt J Deall D.S.O. D.F.C. N.F.C., (Deputy C.O.) Major H H C Holderness D.S.O. D.F.C. A.F.C. Commanding Officer,

Capt A N Brooks, Capt D McGibbon D.F.C., Lt J M Malloch. Absent Lt C.W. Baillie.

Additional members not present: Alan O’Hara, Basil Hone, John Hough and Owen Love.

Picking up names from my log book I note that I flew with Bill Baillie, Hardwicke Holderness, Johnny Deall, Neville Brooks, Don McGibbon, Alan Douglas, Ossie Penton, Tony Chisnall (R) , Basil Hone during the first four months. The aircraft flown were mainly the Harvard, but there was further training on the Auster and basic introduction to the Rapide and Anson. The main concentration was on Battle formation and something I notice is described as EXPERIMENTAL FLYING.

The Squadron Photo attached dated 1950 and taken in front of a Harvard includes I believe the full complement of the founder members listed, below:-

Back Row (Left to Right) Lt D J Richards, Lt D F Bellingan, Lt J C K Campbell, Lt J A Konschel, Lt D M Whyte (R) (Adjutant), Lt D M Barbour, Lt B T A Hone, Lt 0 D Penton

Front Row (Left to Right) Lt D A Bradshaw, Lt A J Douglas, Capt J Deall D.S.O. D.F.C. N.F.C., (Deputy C.O.) Major H H C Holderness D.S.O. D.F.C. A.F.C. Commanding Officer,

Capt A N Brooks, Capt D McGibbon D.F.C., Lt J M Malloch. Absent Lt C.W. Baillie.

Additional members not present: Alan O’Hara, Basil Hone, John Hough and Owen Love.

Picking up names from my log book I note that I flew with Bill Baillie, Hardwicke Holderness, Johnny Deall, Neville Brooks, Don McGibbon, Alan Douglas, Ossie Penton, Tony Chisnall (R) , Basil Hone during the first four months. The aircraft flown were mainly the Harvard, but there was further training on the Auster and basic introduction to the Rapide and Anson. The main concentration was on Battle formation and something I notice is described as EXPERIMENTAL FLYING.

Best described I think by Hardwicke Holderness in a letter to me dated 15th September 1994. In his lead in he describes himself as an "incompetent about-to-be eighty year old with defective memory" (my reader can judge for himself!?).

I quote "Actually I have been thinking quite a lot lately about flying during that period of Aviation history -- World War II and its aftermath -- and come to the conclusion that we were surely the most privileged flyers of all time! For many reasons: that beautiful breed of then new, streamlined aircraft, powerful and strong enough to do anything in; the quality of the contact we had with them, electronics-free (touch on the controls, intimacy with stalling characteristics...); the opportunity, and necessity for war purposes, to fly them to their aerodynamic limits; the relative emptiness of the sky to do it in without today's sealing- in for pressurisation; the relative freedom from ground control... Lucky, weren't we?" (See Also Addendum 1 attached)

Basil Hone writes "I think it is worth expanding a bit on this and other aspects of the squadron's flying programme. Fighter boys tended to fly with more dash than finesse. Hardwicke and his flight commanders wanted us to have both skills. Experimental - otherwise called limit -- flying was to teach us to fly on the stalling margin; how slowly can you keep the thing flogging straight and level through the air; how slowly can you turn it; how quickly can you recover a stall etc. Equal importance was placed on "dash" at the other end of the envelope!

Grid recce was to teach us how to find the piccanin kia.(toilet)

Instrument flying skills had to be improved so we could operate within narrow dimensional limits. My personal experience was that I came to realise what an incompetent pilot I had been at the outset, while feeling good about my ability to fly at the end. "

I note also that the Auxiliary Squadron did the Kings Birthday parade flypast on June 8th. The parade was at the old Drill Hall, Moffat Street.

Flying for July, August, September saw a similar pattern and in this period I pick up the names of John Campbell, Derek Hallas, and Bill Bailie. September 11th saw us put up an Occupation Day flypast!!

INKOMO CAMP AND KUTAMA STRIP

Mid September saw us combining with the Army for the first deployment exercise. We were initially deployed on 14th September to Inkomo -- Operating from there for several days -- then the engineers built us (overnight from scratch) a forward airfield at Kutama and early morning September 18th we flew in to take up occupation.

Kutama

L-R Brooks - Barbour - ? Moss - Whyte - Deall - ? Konschell - ?

At this point it should perhaps be stressed that the Southern Rhodesian Government had committed to NATO that the country would provide Two Squadrons that would operate in the role of low level ground attack. No. 1 Squadron SRAAF was in fact the first of these Squadrons and was the only operational Squadron of the Southern Rhodesian Air force at that time and was manned entirely by Auxiliary Pilots (unpaid and without even travel allowances or expenses of any sort). The supporting ground crew were entirely Regulars.

To return to Kutama, by 0800 hours the advance airstrip was fully operational and in Auster SR53 Dicky Bradshaw and myself were airborne on the first "Recce". If my memory serves me right another Auster and & Harvard also went up on "Recce" at the same time. By 1100 that morning between us we had discovered and detailed the entire forces of the "enemy" (one of the reasons which was undoubtedly a lesson of the whole exercise was that the enemy had not learnt to remain absolutely motionless when we came over low level) so the whole exercise had to be abandoned. The Army were given the rest of that day and night to redeploy.

The exercise started again the next day with a whole bunch of new rules and the Squadron very much restricted as to how they could operate. The Army had complained that Dicky and I had not played fair as we had flown below the level of the trees. (Damn it we were a low level ground attack Squadron and considered low flying our speciality). The 19th and 20th saw me doing ops "Recces" with John Konschell in a Harvard. The afternoon of the 2 0th saw us returning from Kutama to Inkomo.

A feature of the Kutama Camp was the fact that it was literally in the bush and I have a prized photo in my logbook of myself on the longdrop (below) taken by Johnny Deall. Firmly etched in my mind were the nightly sessions of Cardinal Puff under the experienced Cardinal Neville Brooks. Incidentally our first squadron adjutant was John Moss (R) who was with us at both Inkomo and Kutama --he was later replaced by Doug Whyte (R). On the 21st at Inkomo we had an aerobatic competition and I recorded that I came third; John Moss advises that he came 2nd and that Johnny Deall won the competition.

Toilet Facility - The Long Drop

The 22nd saw the finale of the Inkomo camp when we did a fly past at the final parade and on the 23rd we returned from Inkomo to our base which was of course Cranborne.

October to December 1950 saw us concentrating on battle formation, air to air quarter and head on attacks, this in Harvards with cine cameras. This is probably a good moment to record that the Auxiliaries flew either at dawn before work or in the evening after work or over the weekends. This in particular put a load on the ground crews who not only had to support us but the regulars ' programme as well. It was just great being part of a small compact Air Force and I cannot laud the efforts of the ground crews too highly, they were certainly a dedicated bunch. Of particular significance was the fact that we were small enough to know everybody by name and indeed their families and children. A situation unparalleled in my service career.

January 1951 in anticipation of the first Spitfire Ferry saw us working hard on a couple of old Spitfire manuals and concentrating on instrument flying. On January 9th I see I had a detail under the tutelage of Sergeant John Hough (R).

The Mess - Cranborne

L-R Douglas - Hone - Wood - Bellingan - Konschel - Holderness

Barbour

The Mess- Cranborne

Bradshaw - Penton - Campbell - McGibbon - Richard - Brookes

Hawkins

The Herald March 23 1951 which reported the arrival of the Spitfires and the successful conclusion of the first Spitfire Ferry quoted the team as:

"DAKOTA CAPTAIN Capt. H Hawkins (R) ; Co. Pilot J P Moss (R) ; Radio Operator Capt. W F Jenkins (R) (loaned by the Army); Navigator C.Sgt A Atherton (R).

The Spitfire Pilots, Lieutenant D A Bradshaw; J M Malloch; D M Barbour; B T A Hone; D F Bellingan; 0 D Penton; all No.l Squadron SRAAF.

The Regulars were Capt. RAJ Barber; Sgt-Major J H Paxton; W.0.1 J H Deall; W.0.1 I M Schuman; R Blair; J Hough.

The Ferry being led by the Southern Rhodesian Air force Boss Lt Col Ted Jacklin (R). Sgt N Nel was the Flight Engineer and the engineers who serviced the Spitfires were under Capt M H Gibbon; Sgt Major C Jones; F Burton; I Nesbitt; E L Patrick; C Goodwin all Regulars".

I met up with the team at the Strand Palace Hotel in London. A few of us got together and decided to hire a car whilst we were in the UK so that we could have team transport. I think there were four of us in the syndicate but I can only remember for sure Harold Hawkins, Basil Hone and myself. Whilst we were in the process of hiring a car, a black Ford Pilot we noticed that there were penalties in the insurance clauses against pilots which would have had the effect of tripling the insurance rates. Naturally each of the syndicate had to pass the insurers driving test although we were driving on Southern Rhodesian visitors to the UK licences. We were all in the car at the same time enjoying watching each other sweat in the London traffic.

Basil was the last in the hot seat and you can imagine our consternation when the instructor turned to him and asked "what are you chaps doing over here?" and his reply was we are flying Spitfires back to Southern Rhodesia! There was a deadly silence while we all grimaced to ourselves but the instructor was a good sort and pretended he didn't hear.

I am a bit vague about how we got to Derby but:-

DERBY

We spent a most interesting 10 days with Rolls Royce at Derby learning we hoped something about the intricacies of the Griffin 61 engines powering the Spit XXII. Apart from the technical side unquestionably the highlight was our visit to the "Dogs". We stayed in a small hotel and became great pals with one of the waiters who was a first class chap and as it turned out a steward of the Greyhound stadium. He invited us to spend an evening in the members lounge at the stadium as his guests provided we went in our uniforms. About three quarters way through the racing (only Dickie Bradshaw was winning any money) low and behold in the next race there was a dog called DB. (There were three DB's in our team, Dickie Bradshaw, Densel Bellingan and myself) -- of course all the Airforce £ds and a lot of our new found

member friends bet heavily on the dog -- the damn thing came out of the kennel backwards and was a comfortable last (inept like my golf).

The evening ended with a lively sing song lead by Harold Hawkins and a great Conga Eel weaving its way around the members lounge!!

Nor can I remember exactly how we got to Brize Norton but the Ford Pilot was certainly still with us.

Rolls Royce - Derby - Most of the First Ferry Team

BRIZE NORTON

This was a long established RAF base which had been taken over by the US Army Air Force who were still operating from it in 1951. In the hangers were the brand new Spitfire 22's which had been moth balled in cocoons after the war. The ground crew, who were in fact civilians contracted to the Air force, together with our own ground crew were responsible for removing the aircraft from the cocoons and making them airworthy for air crew training and the Ferry back to Salisbury.

A number of the regular Spitfire pilots on the Ferry despite being experienced were in fact NCO1s. Any ex World War II pilots joining the post war regular Southern Rhodesian Air Force at that time had to start at the bottom, (I think in fact as Sergeant pilots). For example our Auxiliary Squadron deputy boss Captain Johnny Deall had resigned from the Squadron to join the regular force shortly before the Ferry; despite being the Deputy Leader of the Ferry Johnny was at that stage a Warrant Officer (having been hastily promoted from Sergeant for the Ferry). All the Auxiliary pilots, and I think there were six of us, were Lieutenants.

The first shock of Brize Norton was in the Officers Mess (we had all been brought up in the very male chauvinist RAF type Mess) so imagine our surprise to find women and children in the American Officers Mess. On entering the Mess dining room for our first meal we noted that the tables were all individual and set for eight people as it was lunch time there was a preponderance of women and children. There was a table with six places filled and in a state of shock we bypassed this last table and set up on one on our own, oblivious to the bleak. On leaving the dining room the Mess President, himself a high ranking Yank officer discreetly called us to one side and told us that in future we had to fill up empty seats before moving on to a new table -- although as guests of the Mess we obviously had to comply at this point in time there was great private groaning and grumbling. By the end of our stay at Brize Norton most of us were converts to the system because if nothing else it meant we got to know a lot of the Yanks and their families. They were particularly good to us perhaps because of our "rarity appeal" as.instanced by the fact that one Saturday night whilst we were there, there was a Mess dance and the married folks put up our girlfriends for the night in married quarters and acted as chaperones (essential in those days).

Whilst on the question of the dance I should perhaps explain that Brize Norton is close to Oxford. Basil Hone and myself had recently (June 1948) come down from Oxford and what with contacts that were still there and in London, where we had spent the last half of 1948, we were able to muster partners for everyone that required one as the Yanks were adamant that we all came to the dance. If I remember correctly a full turnout was achieved. The Ford Pilot did sterling work over that weekend and on one trip we managed to get 19 bodies into the vehicle -- there were only two casualties, somehow in his enthusiasm Dickie Bradshaw managed to kick the Vogue model girlfriend in the eye giving her a black eye (fortunately everybody had taken their shoes off) his excuse was that he was being crushed to death by one of our large girlfriends, Anna Malan from the South African Embassy; an important link in the partner supply chain was an old friend of ours Russell Bailey in London. Being a male non Air force type we had a problem getting him into the camp so we smuggled him in the boot of the Pilot and due to the boot being well ventilated and the weather freezing cold he got a degree of frostbite -- he was the other casualty.

Perhaps it would be as well if I finish the social side of Brize Norton in one go. The Ford Pilot was on duty practically every evening and did sterling service shuttling bodies to and from Oxford and surrounding pubs such as; The Bear at Woodstock, The Dog at Filford Heath, The TrAut, The Perch and many others. In order to minimise the cost to the four hirers a small charge was made for any and all of the trips.

One instance sticks in my mind particularly -- Basil Hone and myself were invited to dinner at the High Table of our old College Wadham. We made an arrangement to meet some of the others after this very posh "dining in" at the Kings Arms (a pub on the corner of the Wadham College grounds) in fact at the end of Broad Street. John Moss was the driver of the Ford Pilot on that occasion so I suspect he must have been the fourth partner. Not having listened to their instructions very carefully they muddled Kings Arms and Kings Head and could not find the pub; whilst cruising up Broad Street looking for it John opened the drivers window and asked a passing student "where is the Kings Head?" Quick as a flash the reply came back "about two and a half feet from his A-hole!" Despite all a satisfactory rendezvous was made.

Another instance of social consequence surrounds our supply of cigarettes. It should be recorded that in Southern Rhodesia we were paying one shilling and 10 pence for fifty Gold Leaf cigarettes (SR currency was immediately convertible into Sterling at par in those days) so the price of 3 shillings and 10 pence for 20 English cigarettes was horrendous. Most of us were running out of Gold Leaf towards the middle of our stint at Brize Norton and were equally short of finance.

Through a Naval cousin of Mike Schuman's Dickie Bradshaw got a free ride in a Naval Corvette to Guernsey not only to sample the Naval hospitality but also to make contact with a long lost relative in Jersey. The initial part of the weekend went according to plan and the hospitality of the Navy outstanding (it cost him five pounds to fly in a Rapide from Guernsey to Jersey). The return however, proved to be a problem, gales had sprung up and due to inadequate anchorage the Navy had to scarper off home and Dickie had to fly back to Southampton and make his way to Brize Norton. (Another five pounds). He pleaded poverty but had brought back with him a huge supply of duty free English cigarettes, I think they had cost him one shilling for twenty and was highly indignant when we all claimed he was profiteering by selling them to us at three shillings and six pence.

The only sporting event I remember was when we took on a side from the station in a friendly game of Rugby. This caused a degree of interest amongst the Yanks and of course practically every one of us was in the team -- I don't remember the result but it was a great mud bath. Basil writes "mention of that rugby game brings back, in sharp form the memory of Harold the Hawk pulling that thin, lanky, dirty, Lancashire A.A. gunner from the bottom of a loose scrum and, when the lad was finally pulled clear, long greasy black hair and all trailing he said to the Hawk strength five "you F-------------------------g Great C--t!"

The Hawk was speechless for once!

Incidentally another feature of the Mess was that when an American Officer got promoted he threw the Mess bar open --a Junior Officer for an hour and a Senior Officer for the evening. Naturally towards the end of our stay we wanted to do something for them as they had all been so good to us, however investigation proved that even clubbed together we couldn't afford to open the Mess bar for an hour such was the difference between our pay scales and theirs -- the Auxiliary Officers were paid the same as the Regulars per day for the duration of the Ferry Trip. In the end we presented them with a couple of engraved beer mugs for the mess from us -- we felt a bit shy doing this as it seemed mean by comparison with their generosity but to our amazement the presentation was an outstanding success.

Now to the flying side of Brize Norton.

We had a very nice crew room and hanger and it was of course most interesting to personally witness the enthusiasm and interest of our ground crew compared to the civilian contract engineers who were really responsible for the work. The aircrew were allowed to help but only on very mundane tasks with the exception of Jack Malloch who was very much more practical and mechanical engineering orientated than the rest of us.

Considerable time was of course spent further learning and revising the handling notes. Naturally the first types to fly the XXII were the experienced senior pilots who had flown Spitfires or the like during the War. The Ford Pilot came into its own once again as whenever somebody went off on their first solo "on type" the rest of us piled into the car and went down to the end of the runway to witness the event.

It should be recorded here that the Griffin 61 engine was capable of developing plus 12 inches of boost and a further six inches when pushed through the gate (18) (operation necessity only, max five minutes). It was recommended that plus 8 inches only should be used for take off! The Engine developed 1540hp at sea level on take off and 2034hp max power at 7000 ft. It was of particular interest that the "fundis" or the first guys had the most initial problems on take off -- presumably being big wheels they pushed her up to 8 or more too quickly -- the torque was incredible because of the power and accentuated by the narrow undercarriage -- most of the early runners ran off the runway (one or two spectacularly). By the time us juniors were sent on our way the order of the day was full opposite rudder trim and catchy monkey gently.

I note that my first solo on type was on February 21st. Can't remember if I held the runway or not but have a vivid memory of lifting off, raising the undercarriage and disappearing into the cloud base before I had time to think (rate of climb plus 4000 feet per minute at sea level -- so it is not surprising that it didn't take long to get to the cloud base which was about 2000 feet).

It may also be of interest to record that the ground crew set up one of the Spitfires on jacks and I think all of us but certainly the juniors had to be able to sit in the cockpit and simulate a full circuit blindfolded before we were let loose on our first solo on type -- early simulator I suppose!

My log book shows that I had six familiarisation trips between then and the 12th March when we left on the first leg of the Ferry, Brize Norton to Chivenor, North Devon. A total of 5 hours 25 minutes on type. The last two trips are logged as long range tank operations and circuits and landings.

MARCH 12TH

This saw us saying farewell to Brize Norton and the first leg was from Brize Norton to Chivenor. In a way a home from home for Basil Hone and myself as we had done a RAF-VR Oxford University Air Squadron Attachment at Chivenor for two weeks in 1947. It was a grand RAF station (coastal command) if I remember correctly, anyway we were made very welcome. This time round we were careful to keep well clear of the raw Devonshire cider.

Flight time logged was 50 minutes.

Colonel Ted Jacklin had led the Ferry for the first leg and as we did right through the trip we flew in sections of four, four and three. Yours truly was No.3 of the last section. It was at Chivenor that we had our first serious RAF briefing for the Ferry. The RAF took the whole exercise very seriously and we were briefed always by a very senior Officer and usually a Group Captain. We were somewhat surprised to be told that because they considered the Ferry was hazardous we had to operate at all times on the emergency frequency. It was Colonel Jacklin's intention to lead the Ferry for the first leg and the last leg into Salisbury (Cranborne) and a few in between; for all the other legs Warrant Officer Johnny Deall DSO, DFC, NFC, (Dutch DFC) now a Regular was to lead the Ferry. During the War Johnny had commanded 266 (R) Squadron and then as one of the youngest Wing Commanders in the War with a Wing of Typhoons. When the boss rode in the Dak John Moss flew his Spitfire -- Jack of all trades!!

Even after the War class distinction was still pretty strong in the RAF and so when our high ranking briefing Officer asked who was leading the Ferry there was on every occasion a sort of snooty look (as only the English can display) when we said Warrant Officer Deall. However, when Johnny came forward with a chest full of medals and obvious experience the briefing Officer always "out gonged" had the good grace to blush.

By the way we planned to Ferry from Chivenor to Cranborne in seven days -- we were considered an emergency flight as the RAF said that if we got seven aircraft to Cranborne in 30 days it would be good, eight very good, nine excellent and ten a miracle. It was the longest single engine Squadron Ferry that had ever been attempted and the powerful Griffin engine in the Spitfire was apparently notoriously temperamental. Basil Hone reminds me that the Engineering Officer at Rolls Royce Derby said we had to expect problems as (a) it was a true fighter engine intended for short scrambles at Max power and (b) designed for a temperate climate. (A reputation not fully deserved if one considers the whole life of the Spitfires with the Southern Rhodesian Air force).

MARCH 14TH

The second leg of the Ferry which I suppose really should be considered the first important leg was undertaken on March 14th as I did this leg in the Dakota with Harry Hawkins and John Moss my memory doesn't cover any details. However, I believe the intention was Chivenor to litres direct weather and fuel permitting with a possible diversion to Dijon if necessary.

The weather was pretty lousy and so those of us in the Dakota waited anxiously at Istres. I think one section made it direct, the others all more sensibly stopped to refuel at Dijon. The Dakota flight time was 4 hours 10 minutes.

My main memories of Istres were again our surprise at finding that although it was a French Military Aerodrome the eating side of the Mess was in fact a Civilian Restaurant on the station. One of its attractions was table football.

We were astonished when a French Fighter Jet which must have been the forerunner to the Mirage, landed the French pilot hopped out went into the Cafe, had a meal of Spaghetti, bread and a litre of red wine and then took off again, heading West... none of this 8 hours bottle to throttle business!! Certain excitement was also caused by the arrival of the Spitfires but all of this was eclipsed by the arrival of the French Ram Jet piggy backed on a large transport aircraft (type ?). The tandem took off later in the day and the Ram Jet's aerial launch and flight was impressive and highly successful.

The refuelling of the Spitfires for the next leg was also an education, the French ground crews casually went on smoking as they performed this operation (I watched from a considerable distance protected by a fire hydrant) as the long range tanks were pressure fed the fuel spilling was considerable and I nearly had a heart attack when one of the ground crew flicked his lighted cigarette butt into a pool of petrol. Fortunately nothing happened.

MARCH 15TH

We intended to cover two legs this day Istres to El Alouina and then after refuelling on to Castle Benito. Us greenhorns were again warned that our engines would immediately run rough as we got away from land over the sea -- we were assured it was all in the head and a good slug of oxygen would suddenly make the engine run smooth. (By the way a good slug of oxygen also worked wonders on a hangover.)

I was flying Spitfire PK625 and was particularly concerned when the ground crew had to graunch my bubble canopy shut as the winding mechanism had failed. It was all very well for the ground crew to assure me that it was locked shut and wouldn't fly off, I could only think of the stories that you only had 20 seconds to get out of a Spit if you pancaked on the water and what would happen if the emergency charge did not blow the canopy off.

Once again I was flying No.3 of the last section of three aircraft. The sections were in fact designated colour identifications such as red, blue and green but frankly I cannot remember the details. Our section was led by Jack Malloch and No.2 was Charles Paxton. Although I had passed all the necessary tests for the "green ticket instrument flying rating" because I had left early on a business trip to Europe I was an hour or two short of the necessary overall instrument flying time and therefore officially did not hold the rating; due to this I was instructed that if it was necessary to climb into or through cloud I was to remain in close formation with the leader Jack Malloch.

All went well initially particularly after a few slugs of oxygen, then it soon became apparent that we would have to climb up through the predicted cloud. Incidentally we had instructions to avoid Sardinia and only to go the airport at Cagliari as a diversion to land in a case of extreme emergency. Jack called me into tight formation and up we went, Charles doing the normal procedure of altering course 5 degrees to port (No.2) and climbing through the cloud individually with the intention of rejoining battle formation when contact with us was made above. The cloud thickness had been estimated at about 5000 feet. Although it is always eerie being in tight formation in cloud all went well for the first say 2500 feet and then suddenly I had enormous problems holding formation. I seemed to be going from full power to nil in a matter of moments and frustration built up to the point of panic which even a couple of slugs of pure oxygen didn't really calm. My formation was of course lousy but I did manage to hang in there but goodness knows how. You can imagine my surprise/relief when suddenly we came out of the bottom of the cloud obviously something had gone wrong -- the seriousness of the situation was underlined when I noticed only a couple of miles away the top of Monti del xyz (1829m) sticking well into the cloud base.

All this time (as was required of us lessor mortals) strict radio silence had been observed. After a couple of minutes Jack seemed to set course at normal cruise power for the trip (+2 boost) under the cloud. It didn't take me long to notice that there had been a considerable change in the course being steered and a reference to my maps indicated that we seemed to be heading for Cairo rather than El Alouina. After a minute or two I broke silence and suggested to Jack that we were on a wrong course and were likely to drop into the sea well short of Cairo... A terse response from my leader told me to shut up... Another minute passed and I could stand it no longer and advised my leader that I was changing course and he could do what he liked... Initially there was a parting of ways but shortly thereafter Jack apologised, altered course and came back and we set on our way once again as a team.

On the ground at El Alouina it was discovered that Jack's fuel filters were all but blocked (we had been given dirty fuel at Istres) what had happened in the cloud was that as he was climbing his fuel flow was cut off and his engine starved, and he would have to start a descent, the engine would come back on with a burst and we would start climbing again only to have it cut again etc, etc... We only started going smoothly again when he decided to come out of the bottom. No wonder I was having difficulty holding formation. Though for the life of me I never did really understand why we didn't go into Sardinia as surely regular cuts of the engine constituted an extreme emergency and a continuation over the sea wasn't for him a good plan.

The incident of course called for inspection and cleaning of all the fuel filters on all the aircraft. This took time and several of the aircraft proved to have taken on dirty fuel. This brings me to the point where I feel I should try to explain the intricacies of starting the Griffin 61 engine on the Mark 22 Spitfire. The system was the Kaufman Cartridge Starter... The starter magazine held five or six cartridges which looked rather like large shotgun cartridges... when all the necessary priming had been done controls set, prop clear etc, the cartridge was fired and this turned the engine over and hopefully it started. If one missed starting on the first or second cartridge one was in real trouble and more often than not this meant that all five or six cartridges were used unsuccessfully. This in turn meant that one then had to wait until everything settled and cooled down (say 30 minutes) and then start all over again. Hence the coining of the phrase "duck shooting" and heavy mocking from ones fellow pilots.

The afternoon was well on when all the aircraft had been inspected and fuel systems cleaned, nevertheless it was decided to complete the days leg to Castel Benito. Of the last section Jack and I got airborne but poor old Charles went duck shooting. We circled waiting for him to get airborne but it was finally decided that I should go back and if necessary spend that night with him in El Alouina. (As a matter of policy it had been ordered that nobody would be left anywhere alone) Shortly after I landed Charles got his aircraft going and to my surprise I managed a one shot hot start. It was thus that the two of us set off after the others across the Bay of Sirte. We made two mistakes -- the first being that we forgot we were flying due east and thus were not going to make Castel Benito at last light as we had anticipated but just after dark -- the second was we decided to call ourselves pink section (on the spur of the moment and not wishing to take one of the colours already used) apparently this created a huge TIZ WAZ in control for as already mentioned we were using the emergency frequency and we were therefore perhaps hostile aircraft. However apparently it was soon realised what we had done; great concern however, now rested on the fact that we were going to have to land after dark.

The concern was caused by the fact that none of us had tried a night landing before and we had been warned that due to the short exhaust stubs which would belch flame particularly at low revs forward visibility was almost nil and night landings to be avoided at all costs. On arrival at Castel Benito we were given lots of advice from the tower. As the greenhorn, I personally was amazed and indeed annoyed to be told that I had to land first -- jumping to the conclusion that I was being used as canon fodder!! Anyway all's well that ends well and we both landed safely much to the relief of the whole ferry team. It was then that it was pointed out to me that had the first aircraft made a hash of the landing and blocked the runway it was better to have the more experienced pilot coping in those circumstances.

I note the flying time logged for the day was 3 hours 55.

MARCH 16TH

If my memory serves me correctly it was planned that we would fly from Castel Benito to El Adem and on to Fayid that day. The leg to El Adem went without incident and the flying time to El Adem is logged as 2 hours 25. It was at El Adem that two of us, Basil Hone and myself went on the duck shoot of all duck shoots. I for one failed to get the aircraft started with something like 18 cartridges and Basil was not far behind. Presumably as we were both greenhorns and were in different flights none other than Johnny Deall was sent back to spend the night with us on the ground. The mess made us very welcome and showed great interest in the whole ferry.

MARCH 17TH

It was thus that we decided to treat them to split arse formation take off and perhaps even a beat up on departure. Still flying PK625 I managed to horse up the take off... To raise the undercarriage on take off one had to cope with the problem of torque, let go the throttle which was in the left hand to raise the undercarriage lever which was down by the right knee... I had failed to tighten the throttle friction nut sufficiently and in consequence every time I tried to raise the undercarriage the throttle closed on me and obviously with the wheels down and the throttle opening and closing on me I was unable to hold formation. This disjointed gaggle departed ignominiously. Anyway two hours later we landed safely at Fayid where it was Basils turn to round off the day. He taxied or swung off the tarmac runway into the sand and then when he tried to blast his way out the tail of his Spit rose well into the sky and how he didn't put the five bladed wooden prop into the sand nobody knows. Anyway we had rejoined the team safely and had missed the day off that the others had at Fayid (Cairo).

The flight time logged was 2 hours.

MARCH 18TH

The days leg was Fayid -- Wadi Haifa -- Khartoum. I can't remember anything special which is not surprising as it was my turn once again to ride in the Dakota SR25.

Dakota flight time 5 hours.

However, I do remember that the night was extremely hot and most of us lay and sweated on top of our bunks not getting any real sleep.

MARCH 19TH

I notice from my log book that I then flew PK663 and indeed flew it from Khartoum to Cranborne. The reason for the change was that 625 had performed poorly on the long range tests and it was felt that a more experienced pilot should fly it in case a diversionary landing was needed.

The Khartoum to Juba leg was the longest that we were attempting and whilst there was a possible diversion, refuelling there was not certain and in consequence it was hoped that everybody would make Juba. As I am sure you can imagine there were a number of theories as to the best way to handle the engine to ensure maximum range... So perhaps it is appropriate for me to mention that normally we flew in battle formation and used plus 2 boost with as lean a mixture as was sensible... We opened up to plus 6 boost every 15 minutes to clear the engine and when one was flying behind an aircraft it really was interesting to see the black cloud that was emitted... The formation was of course loose as one tried to avoid any unnecessary throttle changes particularly on the Khartoum to Juba leg.

In fact all went well and all aircraft made it to Juba. PK663 did particularly well and I landed with an estimated 25 minutes in reserve. Refuelling confirmed this... the worst aircraft had only 7 minutes in reserve on refuelling which really probably wouldn't have coped with a go round again had that been necessary, in fact we cut things pretty fine.

The flight time logged was 3 hours.

The second leg planned for that day was Juba to Entebbe on the shores of Lake Victoria. My memory fails me as to exactly what happened excepting that just after take off Ossie Penton's Spit blew the glycol coolant lead and lost all his coolant; he displayed excellent airmanship and with considerable skill got the aircraft around doing a dead stick landing causing no further damage -- the engine was of course cooked some reported it as being red hot so he was also lucky. Basil Hone writes "I was a Dak passenger and witnessed the whole show with heart in mouth, from the nasty sounding bang at two to three hundred feet followed by a dense cloud of white smoke from the engine, which quickly turned ominously black!!" Most of us pressed on to Entebbe but some and the Dakota stayed at Juba for the night with Ossie.

Apparently there were a couple of delectable French girls working in the control tower and they caused considerable interest amongst the lads. It was again fiendishly hot and after supper a number of the team went skinny dipping in the airport pool. Consternation was caused when the girls arrived and Ossie has a great story about John Moss heading for the far side of the pool which was darker "as he thought under the water" but in fact with his back side shinning like a moon as he progressed across the pool.

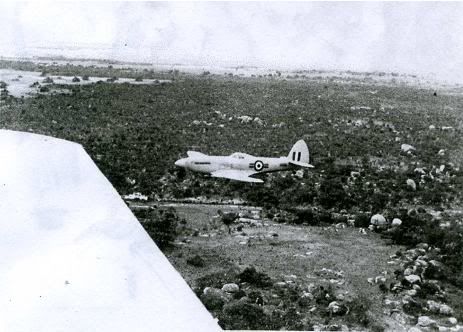

Blair and O’Hara at the pool.

20th MARCH

There was nothing for it but to leave the stricken Spitfire at Juba and the rest of the team and the Dak joined us at Entebbe without further mishap. I note the time logged Juba to Entebbe was 1 hour 35 minutes. An unscheduled day was spent at Entebbe.

21st MARCH

The programme for the day was Entebbe to Tabora for a refuelling stop and then on to Ndola for a night stop. The leg time to Tabora was 1 hour 35 minutes but the refuelling stop was a complete nonsense as it seemed we weren't really expected. However, after a delay we set off to Ndola and landed without further problems, this leg time being 2 hours 25 minutes.

22nd MARCH

The last leg, Ndola to Salisbury (Cranborne) was also a short one and I note it was logged as 1 hour 55 minutes. There was a bit of a shuffle around as Ted Jacklin led the ferry on the last leg home. Although we were flying as a complete ferry of now ten Spitfires we went in sections of 4, 3 and 3. I was still No.3 of the last section. Briefing was pretty thorough as we intended to fly over Salisbury in tight formation and then do a streamer landing at Cranborne. This was the first time we were to do the latter and in consequence there was a degree of concern as clearing the short runway (1100 yards) smartly was of essence and the narrow runway made landing left, right, left, right more academic than factual. Of course as time went on we got rather good at it.

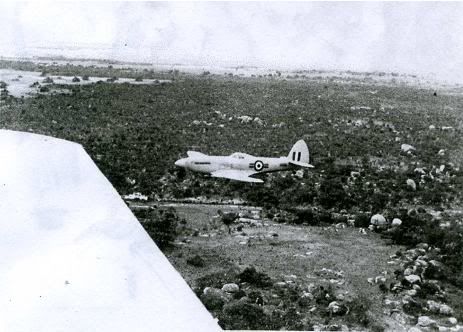

Ray Wood Formats on Dennis Bagnall

I don't remember any incidents but it was great to be back. We had got 10 aircraft back safely in 9 days from the time we left Chivenor and all 10 were in good nick. As a matter of interest a spare engine was flown to Entebbe and fitted to the aircraft left behind and thus "fixed up" it got to Salisbury within the 30 days. Eleven out of Eleven!!

Anyway there was an official reception for us then a party in the mess and home James. I have in my log book some box brownie photos of some of the aircraft on the hard standing when we arrived, of particular interest is the one of Lt Col Jacklin climbing out of PK672, however it is so small that he is barely recognisable.

Arrival First Ferry

Taut - Jacklin - Sir Godfrey Huggins - General Garlake

Arrival of First Ferry PK 672

Ted Jacklin

I think it can be said that without doubt it was a job well done and once again I cannot comment too highly on the efforts of the ground staff who worked willingly round the clock the whole time and to them a major part of the success must be attributed.

It is interesting to note that in his reception speech the Prime Minister Sir Godfrey Huggins said "The Auxiliary Pilots were particularly deserving of praise!"

It is amusing to note that the Spitfires numbers were changed before they were put into service at Cranborne. For instance in May-June I see the aircraft numbers coming up such as SR58, 60, 62, 64. Not completely sure what the real reason was but it was suggested that they wanted to avoid ferry pilots claiming "this is my aeroplane". Naturally of course this led us all to carefully inspect details of the aircraft and its particular characteristics in flight trying to identify "our aeroplane".

MAY 1951

In May 1951 the last of the Royal Air force RATG stations -- Thornhill was to be closed. We, the Auxiliary Squadron were invited to join in their proposed air display and flypast of visiting aircraft.

In this lies an amusing story!

Just why I really don't know but I was asked if I would like to do an eight minute individual aerobatics display at Thornhill showing off our new Spitfires. Whilst flattered to be offered the opportunity I was a bit nervous as I had little more than the ferry time on the aircraft. However as I was promised practice time all three hours of it, and help from my elders and betters, I said thanks. (I was also encouraged by the fact that although it was to be basically low level the A.O.C. Middle East, who was going to be present, had decreed absolutely nothing below 250 feet).

I set off on my first practice run and found a row of gum trees somewhere out near Marandellas which I decided to use as an indicator of Thornhill's runway. I had decided to start the display with a half roll aiming to build up to max speed as I pulled out from the inverted position and also aiming to get to 250 feet just before the beginning of the runway so that I could do a max speed run up the runway until level with the main spectator crowd which presumably would be in the middle of the runway, there I intended to pull up vertically doing three vertical rolls (the fundis had assured me that this was all "a piece of cake") .

Anyway I went up to what I considered a practical height rolled onto my back put on 12 inches of boost and started pulling through (I think I started at 5000 feet above the ground). Half way round I realised there was absolutely no way I was going to make it and even with chopping the throttle and half rolling out the other way and pulling plenty "G" I only just skimmed over the top of the gum trees. What a helluva start!!! This did my nerves no good at all and with trembling hands and feet I gingerly climbed back up to considerably greater height. It took sometime to build up courage to give it a second go but this time I not only had more height but I didn't put the power on until I was well round in the half loop. Now the start manoeuvre worked reasonably well, although I flicked out of the third vertical roll.

Further practices and a couple of goes using the main runway at Cranborne polished up my performance considerably and it was decreed the show wasn't too bad.

It had been decided that two aircraft would go down, one as a reserve to my self for the individual aerobatic display. This support aircraft was to be flown by Jack Malloch, an experienced war time Spit pilot -- he was to lead the formation of two on arrival at Gweru and for our part in the flypast of visiting aircraft.

Although a great guy and a super operator, it was relatively easy to pull Jack's leg. And so it was on the Friday evening in the mess before the display on Saturday that a not to be missed opportunity arose. Jack came to me and threatened me with instant death if I chickened out of the show claiming that he had not had the practice to put on a show himself!! Of course I seized the opportunity and told him very confidentially that I really was very green and very nervous and wasn't at all sure that I would be able to put on the show. A positive aspect of this was that he then came back with a claim of "what the hell am I going to do if you do chicken out?" My suggestion was that instead of trying to do a makeshift display up and down the runway as I had planned he should go at right angles to the runway and do a series of very fast beat ups backwards and forwards over thecrowd pulling up into climbing rolls for altitude and the return.

Anyway Saturday dawned bright and clear with Jack still swearing serious retribution if I failed to perform. We decided we would fly to Thornhill in very loose formation so that I could practice rolls all the way there -- getting into tight formation just before arriving in Gwelo to do a flyover of the city and going into Thornhill.

About two thirds of the way there whilst in the middle of a barrel roll my cockpit was suddenly filled with acrid smoke... Apart from giving me a hell of a fright it cleared quickly and after an anxious 5 minutes of soul searching I told Jack that everything seemed alright and we proceeded as planned.

On arrival at Thornhill, the supporting ground crew who had come down with the Dakota gave my aircraft a real going over but could find nothing wrong. After an early light lunch we all assembled for the general display briefing -- my second shock of the day occurred when the AOC Middle East who was sitting in on the briefing introduced the Southern Rhodesian contingent and as a throwaway remark he said that the height restriction of 250 feet didn't apply to us -- for reasons you will recall this caused me a serious attack of nerves which I just hoped Jack hadn't noticed as of course the previous threats were all a joke. Anyway FORTUNATELY I decided that I was better to perform as practised and not try to bring the whole sequence down appreciably lower except perhaps for the first run.

The general display went absolutely spot on to time, Jack and I took off and proceeded to the holding point from where I would position for my display. While holding I suddenly realised that my radio had gone dead and cockpit lights were fading. I hand signalled to Jack that I was going in on time and he appeared to acknowledge understanding of the message. Well... about half way through my eight minutes I was doing an inverted run up the runway and when approximately at the middle of the crowd I suddenly realised that an aircraft had whistled below me at right angles and at considerable speed (thank goodness for the 250 feet). Stupidly my reaction was not to abort but one of irritation jumping to the conclusion that Jack had decided my display was so bad that it was essential for him to join in. I didn't see him again for the balance of the display but after waiting for about 5 minutes at the rejoin position for the flypast I caught sight of him and was able to move into formation... As had happened once beforeI suddenly had difficulty holding formation and then realised he had his wheels down so I followed suit and moved behind to land (I afterwards discovered that he had done the flypast of visiting aircraft on his own). On landing together with the other visiting aircraft we were to park facing the crowd in line abreast, takeup a position in front of our aircraft for the ceremonial lowering of the Air Force flag for the last time. Whilst Jack and I were a whole aircraft apart he managed to swear at me loudly to which of course I retorted "what the hell do you think you were doing?". After the ceremony we were invited to the VIP tent for sundowners, we had a quick soft drink as we intended to return to Cranborne straight away. My no radio position was not of consequence as we were flying formation.

It was at this 'do' that we learnt that our synchronized show had really gone rather well so we kept our mouths tightly shut. Apparently on two occasions, the one mentioned above, we had very near misses that looked quite spectacular -- one of the things that had worried me about my show was that in an attempt to show off the speed of the aircraft as well as its manoeuvrability there were a number of gaps when I had to climb for a bit of altitude and apparently these were well filled in by Jack. The powers that be apparently thought this whole show was rehearsed.

Our personal debriefing revealed that the general show had suddenly got a few minutes ahead of time and control were desperately calling me in to start my display... when they couldn't get me to respond they called Jack in as the reserve.

Jack claimed he really didn't understand that I was going in on time and thought that I had aborted. He also claimed that all he did was beat up the crowd as discussed in the mess the night before, and said he never saw me until I joined him just prior to landing. I was never rebuked for my unquestionably bad airmanship as we both considered ourselves lucky and kept the whole business of the dual show to ourselves. None of the others let on what had happened. Incidentally it was discovered that my generator had burnt out.

THE MORAL OF THE STORY IS OF COURSE NO DISPLAY SHOULD BE ATTEMPTED AFTER DISCUSSION IN THE MESS AND WITHOUT PROPER PRACTICE.

JUNE/AUGUST 1952

It must have been at about this time that we moved over from Cranborne to the new and very up market NEW SARUM BASE. The Air Force side of the "to be" new Salisbury International Airport. The Air Force side opened up well before the civil operations came over from Belvedere. Whilst the facilities were very much better -- particularly the runway -- it just was never the same. For us too big and too impersonal. A sad but inevitable comparison with Cranborne.

As we have just discussed the air display may I record two related events. From my log book I notice we did an air display at Cranborne on the King's birthday, 7th June 1951.

Whether it was on this display or another I cannot remember but I do know that on one occasion I once again was having difficulty keeping up with the formation due to loss of power when I was on the outside turn -- and kept having to beg the leader to reduce power, under my breath swearing at him for using too much power. It is of great credit to the Griffin engine that I was able to keep some semblance of reasonable formation for when we landed it was discovered that my engine had five pots out of action.

The other was a very sad event indeed. At the Air force's first display at New Sarum the Rhodesia Herald estimated the crowd at 20,000. The RAF from Thornhill planned and did a farewell flypast of 12 Harvards in the formation of "E" for the new Queen Elizabeth II. At lunch in the Mess they were discussing the breakaway tactics for the 13th aircraft (a reserve). In practice they had apparently taken off-in vie formation...did a flypast in that formation with the reserve aircraft in the box of the last vie...this was at a height of about 1000 feet... the reserve aircraft merely breaking away and returning to Belvedere to land and await the others. Over lunch it was decided that this was a bit tame(?) and that the reserve aircraft was to dive down from his back position pulling up in front of the formation doing a victory roll and then disappear off to Belvedere. (UNPLANNED UNPRACTICED MANOEUVRE). Anyway the reserve aircraft attempted this manoeuvre and although at the bottom of his dive he had got well ahead of the formation when he pulled up in the roll the loss of speed took him in the inverted position straight into the formation.

Obviously he was unable to see that he had lost relative position and the result was a mid air collision over the crowd. Two aircraft were certainly involved with a third I think slightly damaged. One crashed within 100 yards of the crowd killing both the occupants (most of the aircraft had a member of the ground staff in the back seat) the other I think had only a pilot who was also killed. The RAF pressed on and flew their "E" formation with a couple of gaps. The whole thing I think had been planned as a farewell to Southern Rhodesia -- all very unfortunate.

Whilst I am on matters general I should perhaps record that the structure of the No.1 Squadron SRAAF was: -

Supported by regular ground crew all the pilots were volunteers (initially we were fourteen strong) -- all were qualified pilots mainly from the war time SRAF and RAF -- the senior pilots ie. the CO, Deputy CO, Flight Commanders and say two or three others were fully operationally experienced; the balance were younger pilots such as myself with little or no operational experience -- this gave the Squadron an IMMEDIATE OPERATIONAL ABILITY and also the know-how to pass on to the younger element. As I understand it when we had grown to the NATO requirement of two Squadrons the senior personnel would retire in rotation as the juniors should be in a position to take over.

Behind this from almost the very beginning the regular SRAF undertook a responsibility to train Auxiliary Volunteer Cadets from "ab initio" to wings so that they could provide the ultimate and continuing follow-on feeding the Squadrons. The first of these joined the Squadron in about 1951, names that I can remember are Peter Potter, Bruce MacKenzie, "the artist" Dennis Bagnall etc, a number of others were under training when the Squadron was wound up in July 1953 (amongst these was Mick McClaren).

JULY 1951

THE SPITFIRE SQUADRON PHOTO MUST HAVE BEEN TAKEN ABOUT THIS

DATE AND INCLUDES:

Back Row (Left to Right)

Lt O.D.Penton, Lt D. Richards, Lt D. Bagnall, Lt B. McKenzie,

Lt A. O'Hara, Lt D. Bradshaw,Lt J.Konschel, Lt J.Campbell,

Lt B. Hone, Lt D. Bellingan, Lt P. Potter, Lt P. Pascoe,

Lt G. Forder D.F.C., Lt R. Wood.

Seated (Left to Right)

Lt A.Douglas, Capt J.Deall D.S.O. D.F.C. N.F.C.,

Major H. Holderness D.S.O. D.F.C. A.F.C., Capt N.Brooks,

Capt D. McGibbon D.F.C.

Absent Capt C.W. Baillie, Lt J.M. Malloch, Lt D.M. Barbour.

Reverting to my log book I see that the flying July to September covered such exercises as experimental flying (angle of attack) and practice demonstration. I note that on September 2nd Ben Bellingan and myself conducted an unsuccessful search and rescue mission for Auster VP-YFL along the Zambezi River -- so we obviously were responsible for search and rescue. (Presumably only over the weekend, when we did most of our flying)

OCTOBER 1951

October to December 1951 saw us concentrating particularly on instrument flying.

Anyway to get back to matters general the last half of 1951 was particularly interesting for us as we were on standby to go to Korea -- at least this is what headquarters told us and with hindsight we wondered if it was a ploy to keep our interest at a high. It certainl made the Friday evening lectures a lot more interesting as we had visiting pilots from the South African Air Force to brief us on the Korean War and other interesting specialist

We certainly took the whole Korean Scene seriously for I remember considering postponing our wedding.

Incidentally just after the first ferry Dickie Bradshaw and Ossie Penton resigned the Auxiliary and joined the permanent force.

Late 1951 Basil Hone had a car accident and seriously damaged his right arm. fortunately he was a left hander... however the powers that be much to his chagrin decide he couldn't fly the Spit as they thought his weakened right hand would not be able to cope with the brakes -- the brakes on the Spit were a pistol grip on the control colum coordinated with pressure on the top part of the rudder pedals. Anyway Basil became our check out pilot in the Harvard and anyone that hadn't flown for a few weeks had to do "refamil" with him, and he took over most of the I.F. training.

(By the end of 1951 the SECOND Spitfire ferry had taken place and 9 new Spit XXII arrived safely from the UK; I notice that the numbers of the aircraft flown jumped from the 50's and 60's to a mixture of them and 70's and 80's). (SEE JOHN CAMPBELL'S ADDENDUM II COVERING THE SECOND SPITFIRE FERRY)

Editor notes: Although Dave Barbour did not participate in the second ferry, most of the photographs he provided are from that ferry. Here are some of them.

Abingdon - December 12, 1951

Second Spitfire Pilots

Techs and Pilots.

Wood (T),Campbell (T), Pascoe (P), Blair (P), Hawkins (P) Richards (P)

Paxton, Penton, Cunnison and Wood (T)

Dave Richards pranged his Spitfire on landing at Entebbe

Uganda causing extensive damage. The aircraft was however

repaired and eventually reached Rhodesia.

Editors note: Not given in Dave’s account is the composition of the 2nd Ferry.

Regular pilots: Auxiliary pilots:

Lieutenant Bobby Blair Lieutenant John Cambell

Ted Cunnison Alan O’Hara

Bill Smith Peter Pascoe

Sergeant Ossie Penton Dave Richards - crash landed Entebbe

Ray Wood

Sergeant Owen Love – Died on impacting a mountain in France.

James Pringle – Tech team leader observes oversees

maintenance.

Paxton (Dakota support team) watches engine fitter at work

Left – Penton, Blair, Terry Weston (T) and Cunnison

Arrival of First Ferry

Baillie and Barbour

(My flying first half of 1952 was very little, presumably as I got married on the 1st March and combined a honeymoon with a fairly extensive business trip to Europe). It must have been about this time, April '52 that Hardwicke retired and command of the Squadron was taken over by Capt Charles (Bill) Baillie. Cranborne trained and an ex WWII Typhoon pilot who had operated them both in the fighter and fighter bomber roles the latter mainly against VI sites. He was shot down and spent the last 12 months of the war as a POW in Germany.

It was our practice to do exercises in the Harvard and when we had them buttoned up do them in the Spit. The object of course to conserve Spitfire hours as not only were they expensive but the time between major overhauls was relatively short. I also seem to remember that the overall engine life was surprisingly short.

July to September 1952 saw my flying mainly on the Spitfires concentrating on G3 and G4, air to air and tail chases and mainly using syncronised cine cameras. I notice that October to December 1952 all my flying was on the Harvard and it was all air-to- ground, low level and high level bombing. I notice also that we swapped seats front and back and this presumably to monitor each others performance. Cannot remember why but I also see that Alan O'Hara and myself did a bit of flying in the Auster and the Tiger Moth during November described as Display Practice. Neither memory nor log book detail any display.

Another important event which must of taken place the second half of 1952 was the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II -- the Squadron was honoured in that it was asked to nominate a pilot to go to the Coronation and take part in the parade. After considerable discussion it was decided that the youngest and newest member of the Squadron should be sent and that was Peter Potter. It was a marvellous experience for him and he returned really fired up.

On his return his first trip was a refamil with Basil Hone -- I was in bed with flu and at about 2000 hours that Saturday evening one of the Squadron came to tell me that Basil and Peter had been killed in a low flying accident in Seke. Subsequent analysis showed that whilst low flying they put a wing tip into the ground; the result was spectacular and the survival miraculous -- the Harvard cartwheeled wingtip to nose to wingtip leaving the engine behind and the wing and centre section which contained the fuel tanks wrapped around a tree -- it then went on to its tail and left that behind and finally what was left slid along the ground upside down. Saved by the crash bars it turned out that Peter Potter only had serious concussion whilst Jos Nangle, the orthopedic surgeon on call, worked on Basil for an hour before he recognised him (he had sorted out Basil's carprang arm), anyway Basil had over 140 stitches in his head and survived.

JANUARY 1953

APRIL 1953

April to Sept 1953 was the SWANSONG of the Auxiliary Squadron at the time we didn't know it and really enjoyed more high level battle formation, tail chases and live firing with the 20mm cannons on the range. July 11th and 18th are the last Squadron entries in my log book and I notice that this was the first time we used the rocket fitments. By this time all the aircraft were fitted with the new "Wander Sight"(?) It really was quite remarkable though of course very old fashioned now. I remember we started our run in for rocket attack on a ground target (I think it was 12 feet by 12 feet) from 10 000 feet and released at an estimated 1500 feet this so that the pull away avoided the shrapnel from the rocket. I also remember that I was extremely chuffed to record an average error over four rockets released independently of four feet (one 16 foot wide and the other 3 on target). My elation was short lived as I found I was in the bottom half of the exercise and not right at the top as I expected.

I should record that at this stage we had I think it was 24 pilots on the Squadron and were very close to separating into No.l and 2 Squadron and thereby meeting the country's NATO commitment .

Excitement was at fever pitch as it had now become certain that the SRAF was going to be equipped with Vampires. As the operational element of the Air force we of course assumed that we would be so equipped and had in fact started studying the Aircraft and Engine manuals. We knew that none of us would go on the Vampire ferry as only four aircraft were being brought out initially but we looked forward to the regulars converting us once they had returned.

As I have already mentioned it was our practice to meet at 1630 every Friday for a three hour lecture and ground education stint followed by the Friday night "Beer Drink". It must have been sometime after 18th July that "the coupe de grace" was delivered -- One Friday evening Colonel Jacklin was overseas on the Vampire Deal and it fell to the lot of Major Keith Taute to inform us that the Auxiliary Squadron was to be washed out. Our surprise was complete to say the least of it as up to this point no rumours or any other information along these lines had reached us. We were even more surprised, and dare I say offended, to be asked to parade NEXT WEEK ON THURSDAY to be thanked by the PM and disbanded -- this after three and a half years dedicated and unpaid service as a Squadron, in my case four and a half years.

Postponement was denied as we saw it by a bunch of blockheads at headquarters -- anyway we declined to parade and we understand the Prime Minister thanked a ghost Squadron. Naturally the powers that be weren't impressed with us but they FAILED COMPLETELY TO APPRECIATE THE DEPTH OF COMMITMENT THAT EVERY SINGLE ONE OF US ON THE SQUADRON FELT TO THE JOB WE WERE DOING -- the value of our contribution towards building an effective post war Southern Rhodesian Air Force -- not to mention our support of the country's contribution to NATO.

Perhaps this was a classic example of pride riding before a fall!

Anyway for at least six to twelve months we continued meeting on a Friday evening at 5 o'clock in the Passada Bar, Manica Road. We made numerous approaches with various suggestions as to how the whole NATO commitment could be better handled. Our suggestions were ignored and finally we disbanded ourselves having as we saw it behaved very honourably. One Senior Permanent Staff Officer known more for his brawn than his brains or tact described our action as a rebellion. We believe that this is the reason that the No.1 Auxiliary Squadron Southern Rhodesian Air Force only earns a brief three line mention in the history of the force; whereas in fact (don't forget that at the very beginning the Auxiliary Squadron Officers outnumbered Permanent Staff Officers) the Squadron must have been at least a CORNER STONE IN THE WHOLE DEVELOPMENT OF THE POST WORLD WAR II AIR FORCE IN THIS COUNTRY.

P.S. As far as I am aware there are only three of the Squadron Pilots still licenced and actively flying as we go to press. Ben Bellingan, Dennis Bagnall and the author.

ADDENDUM'S

1. HARDWICKE HOLDERNESS WRITES 17/12/94

Reading David's lively Memoirs reminds me of a special use of the word "amateur" - to mean doing something for the love of it, without pay, and yet with total professionalism. In these mercenary days when money seems to dominate even sport it is touching to remember that young band of "amateur" fliers (war veterans and all) who assembled in mid.1949 to form a Squadron of the Southern Rhodesia Auxiliary Air Force, and the enthusiasm and dedication they brought to the weekly meetings (and beer-drinking afterwards) and to weekend flying.

It was not just a fun thing. The identification of Southern Rhod esia with Britain and Imperial Defence had been amply evidenced in two world wars. On the air side, an Air Unit flying Hawker Harts had been set up as a wing of the Territorial Army several years before the Second World War. I know this because my brother John was one of the first pilots and took part in an epic collection of Harts from Helipolis (Cairo - was it?) and flying them back down Africa to Salisbury - fore runner of the epic collection of Spitfire XXII's which David so graphically describes .

During the War Southern Rhodesian fliers served in Royal Air Force uniform, and the country itself became a sort of RAF base as a major participant in the Empire Air Training Scheme. The postwar Auxiliary reverted to Army uniform and ranks; but like the old Air Unit was effectively an extension of the Royal Air Force, and inheritor of the tradition and expertise accumulated by the RAF and its Central Flying School.

There had been a radical change in the approach to flying and flying instruction during the War, and particularly during the first year of it, due to three factors. The first was the emergence from the old biplane (with its special demands, on the use of rudder for example) of the new, streamlined monoplane. The second was the experience which pilots of the new Hurricanes and Spitfires were having in 1940 and the lead-up to the Battle of Britain and afterwards of actual combat with their German counterparts. The third was the growing need for pilots to do more than imitate what their instructors demonstrated and to

understand and be able to visualise what was going on between the aircraft's wing and its relative airflow. The change can be seen reflected in the difference between the small, 1939 version of the RAF "Principles of Flying Instruction", officially "A. P. 1732", which consisted mainly of model wording to be used by the instructor while demonstrating manoeuvres in the air (generally called "the patter"), and the revised and comprehensive version first published in May 1943.

Take stalling for example. One of the essential skills the fighter pilot found he needed was the ability to out-turn his opponent - to achieve the maximum turn in the minimum time while flying the aircraft accurately as a gun platform, or with deliberate inaccuracy. What that required was total familiarity with its stalling limits - mastery of the aircraft in the lead-up to, at and beyond the stall. In the 1939 "patter" stalling was treated as something that happened at a particular speed varying with different conditions of flight, to be avoided by keeping above that speed. In the 1943 Handbook it is something that happens

to the airflow at a particular angle of attack of the wings which it is vital for the pilot to experience fully and understand.

In the course of instructing on advanced training aircraft like the Harvard and Miles Master during 1940 and 1941 it became increasingly clear that what one had to try to do was to convert a young man with minimum experience on the elementary type - possibly still a biplane - into a pilot with such a mastery of the service type - including steep turns, stalling, spinning, aerobatics and flying in formation while maintaining a vigorous and constant lout-out in all directions - that at the end of the Course he was fit to be put into a Hurricane or Spitfire and, except for some additional instruction in tactics and gunnery,

ready for operations. Some of us became a bit obsessed with the doctrine of what we called "limit flying" and thought it lamentable that any pilots, whether destined for fighters or bombers, should be confined to training on non-aerobatic aircraft the first thing to do was to explore its stalling characteristics.

The aerobatics and the like included in the displays which David mentions (and one at the opening of Livingston Airport in August 1950) were not just showing off, but part of the "Limit Flying" tradition.

I first encountered A.P. 1732 (1939 version) on an Instructors' Course at the Central Flying School, Upavon, in the spring of 1940, and during the rest of that year and 1941 was involved in high-pressure training of fighter pilots in Miles Masters at a Service Flying Training School in Scotland; and in 1942 was a member of the foundation staff (in company with that greatest of teachers of Theory of Flight, A.C. Kermode) of the Empire Central Flying School, charged with the task of revising A.P. 1732 and producing the May 1943 version. During the second half of the war I was mainly involved with flying four-engined Halifax aircraft in operations against enemy U-boats and shipping, but including some instructing on it and on the magical Mosquito (and some brief love affairs on the side with delectable aircraft like the Mustang) and able to satisfy myself that intimacy with the stall was invaluable in every field. If I remember right it is what the Experimental Flying which David mentions was mostly about.

I was privileged to be the first C.O. of No.l (as it turned out, the only) Squadron of the SRAAF. My first and last log book entries in that capacity are dated 11th August 1949 and 2nd March 1952. And I have as a valued possession a silver presentation tray dated "4/4/52" which bears the engraved signatures of all those (except Mackenzie) appearing in the 1951 photograph plus those of C.W. Baillie, D.M. Barbour himself, A.G.Hellas and Jack Malloch, and brings them all touchingly to mind.

P.S. Remember that narrow, bird like undercarriage of the Spitfire? And the challenge presented by all undercarriages of that format, with the tail-wheel, as compared with the "tricycle" type common today? The nose-in-the-air attitude of the aircraft on the ground; the tendency to "balloon" touching main wheels first; the directional instability.... And the enormous sense of achievement if you got to be able with any consistency to put the aircraft down near a given spot in the three-point position?

P.P.S. I wonder how quaint and archaic this kind of stuff must seem to a modern aviator?

2. JOHN CAMPBELL WRITES MAY 1995 COVERING THE SECOND SPITFIRE FERRY

If in Africa Unity Square I shouted "First Lady, Second World War, Third Reich, Fourth dimension, Fifth brigade" I would command attention. If I yelled "Second Ferry" everyone would go on sleeping, run away or call the police!

So this is for those who understand and will be interested in these recollections although having begun I can't remember what happened last week let alone 43 years ago.

The tale of the Second Ferry, like the first, is worth the telling because it is a tribute to No.l SQUADRON SOUTHERN RHODESIA AUXILIARY AIRFORCE (SRAAF) which provided 6 pilots and to the Southern Rhodesian Airforce (SRAF) pilots and groundcrew. This combined audacious operation flew eleven Spitfire 22's from Britain and got nine of them back to Rhodesia.

We benefited from the First Ferry which, eleven months earlier, set of with eleven Spit 22's and arrived home with ten.

Here over my desk I have a fine photograph of all our second Spit Ferry pilots taken at Abingdon just before take off on that cold clear morning of December 7 1951. Lets see if I can remember the names. Left to right standing:- Ted Cunnison (R), who led the flight, Bill Smith (R) , Charles Paxton (R) , John Campbell (A), thats me, Owen Love (A), Bob Blair (R), Alan O'Hara (A), and in front in a relaxed crouch:- Dave Richards (A) , Ray Wood (A) , Peter Pascoe (A) and Ossie Penton (R).

A few minutes later over France the weather forecast failed us and heavy cloud forced us onto the deck so we had to climb through. Most of us did not have much blind flying experience and in a Spit it is difficult anyway. Owen Love did not emerge from the top, he had crashed and died near Paris. Lets begin at the beginning and with the help of my dog eared log book I can say we all piled into the Dakota at Belvedere Airport on November 9th and Captain Harold Hawkins, I/C the operation, and Lt Bill Dawson flew us to Abingdon in 5 days. I can't remember much about the journey except it was hilarious on occasions and the weather around Lake Victoria was awful.

We travelled the route by which we would return which made a lot of sense and this was Kasama, Kisimu, Juba, Khartoum, Wadi Haifa, Fayid, El Adem, Castle Benito, Tunis, Istres and into Abingdon.

Over 2 weeks were spent at Cosford testing the Spits which had just been taken from war surplus cocoons.

During this time we went to Hatfield and elsewhere to fly in Vampires and Meteors because the SRAF wanted our opinions for the jet age ahead. Thanks to an old friend of mine Bill Pegg, Chief test pilot for Bristols, I took some of the lads to Filton to see the Bristol Brabazon which was doing taxi trials.

Overtaken by the jet age she never flew commercially.

A meeting with my brother Iain who was at Oxford was a memorable occasion about which I remember nothing.